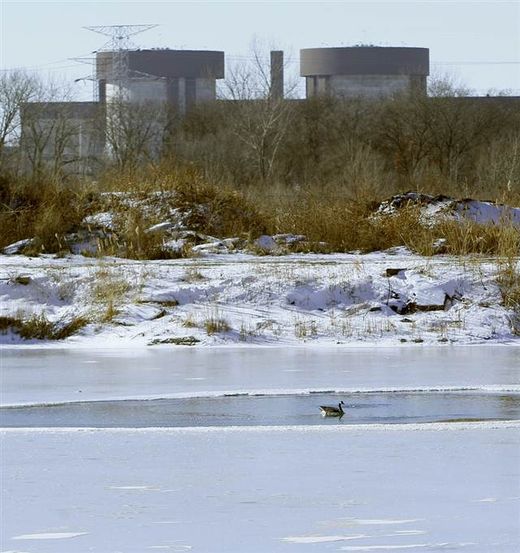

Braceville, Illinois - Radioactive tritium has leaked from three-quarters of U.S. commercial nuclear power sites, often into groundwater from corroded, buried piping, an Associated Press investigation shows.

The number and severity of the leaks has been escalating, even as federal regulators extend the licenses of more and more reactors across the nation.

Tritium, which is a radioactive form of hydrogen, has leaked from at least 48 of 65 sites, according to U.S. Nuclear Regulatory Commission records reviewed as part of the AP's yearlong examination of safety issues at aging nuclear power plants.

Leaks from at least 37 of those facilities contained concentrations exceeding the federal drinking water standard - sometimes at hundreds of times the limit.

While most leaks have been found within plant boundaries, some have migrated offsite. But none is known to have reached public water supplies.

At three sites - two in Illinois and one in Minnesota - leaks have contaminated drinking wells of nearby homes, the records show, but not at levels violating the drinking water standard.

At a fourth site, in New Jersey, tritium has leaked into an aquifer and a discharge canal feeding picturesque Barnegat Bay off the Atlantic Ocean.

Previously, the AP reported that regulators and industry have weakened safety standards for decades to keep the nation's commercial nuclear reactors operating within the rules.

While NRC officials and plant operators argue that safety margins can be eased without peril, critics say these accommodations are inching the reactors closer to an accident.

Any exposure to radioactivity, no matter how slight, boosts cancer risk, according to the National Academy of Sciences. Federal regulators set a limit for how much tritium is allowed in drinking water. So far, federal and industry officials say, the tritium leaks pose no health threat.

But it's hard to know how far some leaks have traveled into groundwater. Tritium moves through soil quickly, and when it is detected it often indicates the presence of more powerful radioactive isotopes that are often spilled at the same time.

For example, cesium-137 turned up with tritium at the Fort Calhoun nuclear unit near Omaha, Neb., in 2007. Strontium-90 was discovered with tritium two years earlier at the Indian Point nuclear power complex, where two reactors operate 25 miles north of New York City.

The tritium leaks also have spurred doubts among independent engineers about the reliability of emergency safety systems at the 104 nuclear reactors situated on the 65 sites.

That's partly because some of the leaky underground pipes carry water meant to cool a reactor in an emergency shutdown and to prevent a meltdown. More than a mile of piping, much of it encased in concrete, can lie beneath a reactor.

Tritium is relatively short-lived and penetrates the body weakly through the air compared to other radioactive contaminants. Each of the known releases has been less radioactive than a single X-ray.

The main health risk from tritium, though, would be in drinking water. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency says tritium should measure no more than 20,000 picocuries per liter in drinking water. The agency estimates seven of 200,000 people who drink such water for decades would develop cancer.

Still, the NRC and industry consider the leaks a public relations problem, not a public health or accident threat, records and interviews show.

"The public health and safety impact of this is next to zero," said Tony Pietrangelo, chief nuclear officer of the industry's Nuclear Energy Institute. "This is a public confidence issue."

Leaks are prolific

Like rust under a car, corrosion has propagated for decades along the hard-to-reach, wet underbellies of the reactors - generally built in a burst of construction during the 1960s and 1970s. As part of an investigation of aging problems at the country's nuclear reactors, the AP uncovered evidence that despite government and industry programs to bring the causes of such leaks under control, breaches have become more frequent and widespread.

There were 38 leaks from underground piping between 2000 and 2009, according to an industry document presented at a tritium conference. Nearly two-thirds of the leaks were reported over the latest five years.

Here are some examples:

- At the three-unit Browns Ferry complex in Alabama, a valve was mistakenly left open in a storage tank during modifications over the years. When the tank was filled in April 2010 about 1,000 gallons of tritium-laden water poured onto the ground at a concentration of 2 million picocuries per liter. In drinking water, that would be 100 times higher than the EPA health standard.

- At the LaSalle site west of Chicago, tritium-laden water was accidentally released from a storage tank in July 2010 at a concentration of 715,000 picocuries per liter - 36 times the EPA standard.

- The year before, 123,000 picocuries per liter were detected in a well near the turbine building at Peach Bottom west of Philadelphia - six times the drinking water standard.

- And in 2008, 7.5 million picocuries per liter leaked from underground piping at Quad Cities in western Illinois - 375 times the EPA limit.

A 2008 NRC staff memo reported industry data showing 83 failed cables between 21 and 30 years of service - but only 40 within their first 10 years of service. Underground cabling set in concrete can be extraordinarily difficult to replace.

Under NRC rules, tiny concentrations of tritium and other contaminants are routinely released in monitored increments from nuclear plants; leaks from corroded pipes are not permitted.

The leaks sometimes go undiscovered for years, the AP found. Many of the pipes or tanks have been patched, and contaminated soil and water have been removed in some places. But leaks are often discovered later from other nearby piping, tanks or vaults.

Mistakes and defective material have contributed to some leaks. However, corrosion - from decades of use and deterioration - is the main cause. And, safety engineers say, the rash of leaks suggest nuclear operators are hard put to maintain the decades-old systems.

Over the history of the U.S. industry, more than 400 known radioactive leaks of all kinds of substances have occurred, the activist Union of Concerned Scientists reported in September.

Several notable leaks above the EPA drinking-water limit for tritium happened five or more years ago, and from underground piping: 397,000 picocuries per liter at Tennessee's Watts Bar unit in 2005 - 20 times the EPA standard; four million at the two-reactor Hatch plant in Georgia in 2003 - 200 times the limit; 750,000 at Seabrook in New Hampshire in 1999 - nearly 38 times the standard; and 4.2 million at the three-unit Palo Verde facility in Arizona, in 1993 - 210 times the drinking-water limit.

Many safety experts worry about what the leaks suggest about the condition of miles of piping beneath the reactors. "Any leak is a problem because you have the leak itself - but it also says something about the piping," said Mario V. Bonaca, a former member of the NRC's Advisory Committee on Reactor Safeguards. "Evidently something has to be done."

However, even with the best probes, it is hard to pinpoint partial cracks or damage in skinny pipes or bends. The industry tends to inspect piping when it must be dug up for some other reason. Even when leaks are detected, repairs may be postponed for up to two years with the NRC's blessing.

"You got pipes that have been buried underground for 30 or 40 years, and they've never been inspected, and the NRC is looking the other way," said engineer Paul Blanch, who has worked for the industry and later became a whistleblower. "They could have corrosion all over the place."

Nuclear engineer Bill Corcoran, an industry consultant who has taught NRC personnel how to analyze the cause of accidents, said that since much of the piping is inaccessible and carries cooling water, the worry is if the pipes leak, there could be a meltdown.

East Coast issues

One of the highest known tritium readings was discovered in 2002 at the Salem nuclear plant in Lower Alloways Creek Township, N.J. Tritium leaks from the spent fuel pool contaminated groundwater under the facility - located on an island in Delaware Bay - at a concentration of 15 million picocuries per liter. That's 750 times the EPA drinking water limit. According to NRC records, the tritium readings last year still exceeded EPA drinking water standards.

And tritium found separately in an onsite storm drain system measured 1 million picocuries per liter in April 2010.

Also last year, the operator, PSEG Nuclear, discovered 680 feet of corroded, buried pipe that is supposed to carry cooling water to Salem Unit 1 in an accident, according to an NRC report. Some had worn down to a quarter of its minimum required thickness, though no leaks were found. The piping was dug up and replaced.

The operator had not visually inspected the piping - the surest way to find corrosion - since the reactor went on line in 1977, according to the NRC. PSEG Nuclear was found to be in violation of NRC rules because it hadn't even tested the piping since 1988.

Last year, the Vermont Senate was so troubled by tritium leaks as high as 2.5 million picocuries per liter at the Vermont Yankee reactor in southern Vermont (125 times the EPA drinking-water standard) that it voted to block relicensing - a power that the Legislature holds in that state.

Activists placed a bogus ad on the Web to sell Vermont Yankee, calling it a "quaint Vermont fixer-upper from the last millennium" with "tasty, pre-tritiated drinking water."

The gloating didn't last. In March, the NRC granted the plant a 20-year license extension, despite the state opposition. Weeks ago, operator Entergy sued Vermont in federal court, challenging its authority to force the plant to close.

At 41-year-old Oyster Creek in southern New Jersey, the country's oldest operating reactor, the latest tritium troubles started in April 2009, a week after it was relicensed for 20 more years. That's when plant workers discovered tritium by chance in about 3,000 gallons of water that had leaked into a concrete vault housing electrical lines.

Since then, workers have found leaking tritium three more times at concentrations up to 10.8 million picocuries per liter - 540 times the EPA's drinking water limit - according to the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection. None has been directly measured in drinking water, but it has been found in an aquifer and in a canal discharging into nearby Barnegat Bay, a popular spot for swimming, boating and fishing.

An earlier leak came from a network of pipes where rust was first discovered in 1991. Multiple holes were found, "indicating the potential for extensive corrosion," according to an analysis released to an environmental group by the NRC. Yet only patchwork repairs were done.

Tom Fote, who has fished in the bay near Oyster Creek, is unsettled by the leaks. "This was a plant that was up for renewal. It was up to them to make sure it was safe and it was not leaking anything," he said.

Added Richard Webster, an environmental lawyer who challenged relicensing at Oyster Creek: "It's symptomatic of the plants not having a handle on aging."

Exelon's piping problems

To Exelon - the country's biggest nuclear operator, with 17 units - piping problems are just a fact of life. At a meeting with regulators in 2009, representatives of Exelon acknowledged that "100 percent verification of piping integrity is not practical," according to a copy of its presentation.

Of course, the company could dig up the pipes and check them out. But that would be costly.

"Excavations have significant impact on plant operations," the company said.

Exelon has had some major leaks. At the company's two-reactor Dresden site west of Chicago, tritium has leaked into the ground at up to 9 million picocuries per liter - 450 times the federal limit for drinking water.

At least four separate problems have been discovered at the 40-year-old site since 2004, when its two reactors were awarded licenses for 20 more years of operation. A leaking section of piping was fixed that year, but another leak sprang nearby within two years, a government inspection report says.

The Dresden leaks developed in systems that help cool the reactor core in an emergency. Leaks also have contaminated offsite drinking water wells, but below the EPA drinking water limit.

There's also been contamination of offsite drinking water wells near the two-unit Prairie Island plant southeast of Minneapolis, then operated by Nuclear Management Co. and now by Xcel Energy, and at Exelon's two-unit Braidwood nuclear facility, 10 miles from Dresden. The offsite tritium concentrations from both facilities also were below the EPA level.

The Prairie Island leak was found in the well of a nearby home in 1989. It was traced to a canal where radioactive waste was discharged.

Braidwood has leaked more than six million gallons of tritium-laden water in repeated leaks dating back to the 1990s - but not publicly reported until 2005. The leaks were traced to pipes that carried limited, monitored discharges of tritium into the river.

"They weren't properly maintained, and some of them had corrosion," said Exelon spokeswoman Krista Lopykinski.

Last year, Exelon, which has acknowledged violating Illinois state groundwater standards, agreed to pay $1.2 million to settle state and county complaints over the tritium leaks at Braidwood and nearby Dresden and Byron sites. The NRC also sanctioned Exelon.

Tritium measuring 1,500 picocuries per liter turned up in an offsite drinking well at a home near Braidwood.

Though company and industry officials did not view any of the Braidwood concentrations as dangerous, unnerved residents took to bottled water and sued over feared loss of property value. A consolidated lawsuit was dismissed, but Exelon ultimately bought some homes so residents could leave.

Exelon refused to say how much it paid, but a search of county real estate records shows it bought at least nine properties in the contaminated area near Braidwood since 2006 for a total of $6.1 million.

Exelon says it has almost finished cleaning up the contamination, but the cost persists for some neighbors.

Retirees Bob and Nancy Scamen live in a two-story house within a mile of the reactors on 18 bucolic acres they bought in 1988, when Braidwood opened. He had worked there, and in other nuclear plants, as a pipefitter and welder - even sometimes fixing corroded piping. For the longest time, he felt the plants were well-managed and safe.

His feelings have changed.

An outlet from Braidwood's leaky discharge pipe 300 feet from his property poured out three million gallons of water in 1998, according to an NRC inspection report. The couple didn't realize the discharge was radioactive.

The Scamens no longer intend to pass the property on to their grandchildren for fear of hurting their health. The couple just wants out. But the only offer so far is from a buyer who left a note on the front door saying he'd pay the fire-sale price of $10,000.

They say Exelon has refused to buy their home because it has found tritium directly behind, but not beneath, their property.

"They say our property is not contaminated, and if they buy property that is not contaminated, it will set a precedent, and they'll have to buy everybody's property," said Scamen.

Their neighbors, Tom and Judy Zimmer, are also hoping for an offer from Exelon for the land and home they built on it, spending $418,000 for both.

They had just moved into the house in November 2005, and were laying the tile in their new foyer when two Exelon representatives appeared at the door.

"They said, 'We're from Exelon, and we had a tritium spill. It's nothing to worry about,'" recalls Tom Zimmer. "I didn't know what tritium even meant."

But his wife says she understood right away that it was bad news - and they hadn't even emptied their moving boxes yet: "I thought, 'Oh, my God. We're not even in this place. What are we going to do?'"

They say they had an interested buyer who backed out when he learned of the tritium. No one has made an offer since.

Public relations effort

The NRC is certainly paying attention. How can it not when local residents fret over every new groundwater incident? But the agency's reports and actions suggest a preoccupation with image and perception.

An NRC task force on tritium leaks last year dismissed the danger to public health. Instead, its report called the leaks "a challenging issue from the perspective of communications around environmental protection." The task force noted ruefully that the rampant leaking had "impacted public confidence."

For sure, the industry also is trying to stop the leaks. For several years now, plant owners around the country have been drilling more monitoring wells and taking a more aggressive approach in replacing old piping when leaks are suspected or discovered.

For example, Exelon has been performing $14 million worth of work at Oyster Creek to give easier access to 2,000 feet of tritium-carrying piping, said site spokesman David Benson.

But such measures have yet to stop widespread leaking.

Meantime, the reactors keep getting older - 66 have been approved for 20-year extensions to their original 40-year licenses, with 16 more extensions pending.

And, as the AP has been reporting in its ongoing series, Aging Nukes, regulators and industry have worked in concert to loosen safety standards to keep the plants operating.

In an initiative started last year, NRC Chairman Gregory Jaczko asked his staff to examine regulations on buried piping to evaluate if stricter standards or more inspections were needed.

The staff report, issued in June, openly acknowledged that the NRC "has not placed an emphasis on preventing" the leaks.

The authors concluded there are no significant health threats or heightened risk of accidents.

And they predicted even more leaks in the future.

Comment: Tritium - is a radioactive isotope of hydrogen. The nucleus of tritium (sometimes called a triton) contains one proton and two neutrons, whereas the nucleus of protium (by far the most abundant hydrogen isotope) contains one proton and no neutrons. Naturally occurring tritium is extremely rare on Earth, where trace amounts are formed by the interaction of the atmosphere with cosmic rays. The name of this isotope is formed from the Greek word "tritos" meaning "third."

..

Health risks

Tritium is an isotope of hydrogen, which allows it to readily bind to hydroxyl radicals, forming tritiated water (HTO), and to carbon atoms. Since tritium is a low energy beta emitter, it is not dangerous externally (its beta particles are unable to penetrate the skin), but it is a radiation hazard when inhaled, ingested via food or water, or absorbed through the skin. HTO has a short biological half life in the human body of seven to 14 days, which both reduces the total effects of single-incident ingestion and precludes long-term bioaccumulation of HTO from the environment.