© PS

Drive west across the rocky spine of Vancouver Island along rutted logging roads to the fishing village of Bamfield and stand on the splendid beach at Pachena Bay.

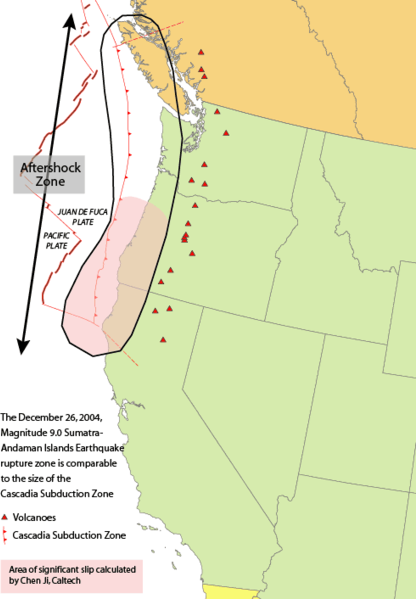

Look out across the surly, roiling Pacific and try to picture a crack in the ocean floor, a tectonic fault known as the Cascadia subduction zone that runs south 1,300 kilometres to Cape Mendocino, the most westerly point in California.

Now imagine a chilly winter's night more than three centuries ago when that fault ripped apart in a deadly, magnitude 9 earthquake.

People of the Huu-ay-aht First Nation, asleep in their longhouses just above the high-tide mark, were jolted awake. The violent shaking of the earth lasted several minutes and left the houses intact. Their occupants survived, but what they could not see out in the dark was a rapidly falling tide.

A dark force was sucking the sea out of Pachena Bay, leaving the sands dry - but only momentarily - as a mountainous wave gathered strength. Suddenly it crashed like a battering ram against the shore, hurtling back into the bay so quickly that the people had no time to reach their canoes.

Everyone died, according to neighbouring villagers who witnessed the tragedy from homes built high on a nearby hill, a story passed down through the generations to the current chief, Robert Dennis, who told me.

Roughly eight hours later, the back side of that killer wave hit the coast of Japan, more than 7,000 kilometres away.

A wakeup call for two nationsFor the past month, Japan has struggled to recover from another deadly tsunami, albeit it one caused by an earthquake much closer to home.

The costliest natural disaster on record has killed as many as 25,000 people, caused an estimated $300-billion in damage and raised the spectre of widespread radioactive pollution.

Such devastation should serve as a wake-up call, a reminder that much of North America's West Coast faces a very similar threat: The question isn't whether Cascadia's fault will wreak havoc once more but when.

I was introduced to Cascadia in 1985 while working on documentaries for CBC-TV's

The Journal. A magnitude 8 quake had claimed more than 10,000 lives in Mexico City, and we wanted to know what scientists had learned from the disaster.

At that point, the earthquake detectives knew about neither the devastation on Pachena Bay three centuries earlier nor the wave that had hit Japan.

In fact, so little was known about plate tectonic theory - how the giant slabs making up the Earth's crust grind past each other - that, until Mexico was struck, the lack of great earthquakes in recorded history led some experts to think that both it and the Pacific Northwest might be exempt from these massive, offshore tremors.

They considered the undersea fault relatively harmless, with the plates sliding past each other "aseismically" and not creating the kind of strain that leads to a quake. But at the Pacific Geoscience Centre on Vancouver Island, laboratory director Dieter Weichert informed us that, because of Mexico, the official risk assessment for a magnitude 8 or higher quake along Canada's West Coast had jumped from 50-50 to 70-30.

Now that science has proof of Cascadia's violent past, the odds are closer to 100 per cent.The first evidence of that violence appeared in legends passed down by the elders of virtually every native community from northern California to Vancouver Island - eerily similar stories of disaster on a winter's night "long, long ago." But nobody could pin down when it had happened.

Then Brian Atwater, a paleoseismologist working for the U.S. Geological Survey, and David Yamaguchi, a forestry specialist at the University of Washington, discovered a "ghost forest" along the state's coast: spruce and cedar trees that had been killed by salt water when the earth suddenly dropped, presumably during a large earthquake, and the forest floor sank below the high-tide zone.

(Similar evidence of large tsunami deposits uncovered on the west side of Vancouver Island and at the head of the Alberni Inlet by John Clague, a professor of earth sciences at Simon Fraser University, and geologist Peter Bobrowsky of the B.C. Geological Survey, suggested a series of huge quakes over thousands of years.) Tree rings and radiocarbon determined that the forest had been transformed into a tidal marsh some time between 1680 and 1720. But that was at least a half-century before recorded history began with the arrival of British explorer James Cook, so doubts remained.

Then, when the Atwater-Yamaguchi study was published, a seismologist from Japan experienced a eureka moment. Kenji Satake, now with the Geological Survey of Japan in Tokyo, realized that a huge earthquake off North America might also have sent a tsunami across the Pacific. If so, the damage may have been worth noting - the Japanese had been writing things down for more than 1,000 years.

He uncovered ancient scrolls that chronicled destruction caused by an "orphan" tsunami (one that seemed to have no "parent" earthquake) along the eastern seaboard of Honshu, Japan's main island, in the winter of 1700.

The surge inundated coastal villages and seaports - many of the same communities that were slammed last month. Ancient castles were flooded, houses were wrecked and fires raced through village streets.

The waves also destroyed bales of rice stored in a government warehouse. In those days, rice was almost a form of currency - taxes collected by samurai warriors on behalf of the shogun - which is probably why documents describing what happened to it now form part of the evidence that Cascadia is active and dangerous.

If the wave was an orphan, Dr. Satake argued, its source must have been across the ocean. Knowing approximately how long it would have taken to reach Japan (in deep water, a tsunami travels at the speed of a jetliner), he calculated that the megathrust took place at roughly 9 p.m. Pacific time on Jan. 26, 1700 - a date consistent with those of both the tribal legends and the ghost forests.

© WikipediaCascadia subduction zone - USGS.

That was Cascadia's most recent major shake. Now, the geologic timeline has been pushed all the way back to the last ice age, and the known number of big quakes has increased substantially.

Drilling into the ocean floor provided marine geologist Chris Goldfinger and researchers from Oregon State University with core samples containing evidence of 41 such earthquakes over the past 10,000 years. Almost half of them were "full margin ruptures" that broke the fault from end to end at magnitude 9 or higher.

Radiocarbon dating has established that 800 years separated some of these quakes, but others were only 200 years apart. The last one, as we now know, took place 311 years ago, so is the next one overdue?

Prof. Goldfinger's study estimated the odds of a quake occurring within the next 50 years in the more active lower part of the fault at 37 per cent, while a recent Canadian study, by Lucinda Leonard at the Pacific Geoscience Centre, calculated a 10-per-cent chance that the entire fault will go within that period.

If the whole fault does tear apart, five major cities - Vancouver, Victoria, Seattle, Portland and Sacramento - would be slammed simultaneously, along with dozens of smaller communities. According to Eddie Bernard of the Pacific Marine Environmental Lab in Seattle, the net effect would be like having Hurricane Katrina strike in five places at once.

Canada has no national guard to backstop local police and fire crews, should the worst occur, and most of its military strength is deployed overseas. Canadian Forces Base Chilliwack, east of Vancouver, once housed the forces' engineering corps, an excellent resource in an emergency, but the base was closed in 1998.

Twenty minutes after the shaking stops, killer waves will strike B.C., Washington, Oregon and northern California. Hours later, "our" tsunami would hit Hawaii, Alaska, Japan, the Philippines, Indonesia, Hong Kong, Australia and New Zealand.

The damage could be staggering, and how well we survive will depend on how well we have prepared. With any luck, the painful experience of Japan will offer a "teachable moment" - a chance for North America to get ready for the inevitable.

If any further reminder is required, both Mexico and Japan were hit with sizable quakes again this week.

So, as well as putting together survival kits, concerned citizens would be wise to spread the word and call for action. The danger that lies ahead is almost unknown beyond British Columbia and the U.S. Pacific Northwest. And that's not Cascadia's fault.

FROM SLIP TO FALLScientists aren't sure when Cascadia's next quake will occur, but they think they know what will trigger it: the fact that, every so often, part of the fault comes "unstuck."

Using highly precise global positioning system equipment, researchers led by Garry Rogers and Herb Dragert of the Pacific Geoscience Centre tracked Vancouver Island's constant tectonic movement toward the mainland. They discovered that every 14 months, the island mysteriously, and silently, slips back toward the west for about 10 days. And then, just as mysteriously, heads east again.

Why? Nobody knows for sure, but it's thought that, as the ocean floor dives under the continental shelf, friction increases until the two are locked and begin to build strain for the next big quake.

But below the locked zone, the rocks are so hot and gooey, they can't stick together. So when the upper plates come apart, a process called "episodic tremor and slip" (ETS) takes place. The island breaks free and jumps back to the west a little. The worry is that, one day, the slip will spark a major thrust.

ACTION PLANSFirst, the good news: When Cascadia strikes, the vast majority of people will survive the initial impact.

The loss of life will be further reduced if "vertical evacuation" shelters are built at strategic locations along the coast, so people can climb to safety above the waves. (There won't be enough time for any other escape.) The real test will be the aftermath, and how well we prepare. For example, public buildings from B.C. to California must be upgraded to serve as emergency shelters.

Even people who don't live in the danger zone may find themselves there on business or vacation when the big quake happens. So all Canadians should have some idea of what to do when the shaking stops.

Resilience is essential - and something that can be learned - by taking a first-aid course or joining an emergency-preparedness group.

Even local governments must be ready. They should rezone seismically dangerous parts of town so residents know that buildings Cascadia destroys can't be replaced.

After all, some day history is going to repeat itself.

Jerry Thompson is a documentary filmmaker living in Sechelt, B.C., and the author of Cascadia's Fault: The Deadly Earthquake That Will Devastate North America,

published this week by HarperCollins Canada.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter