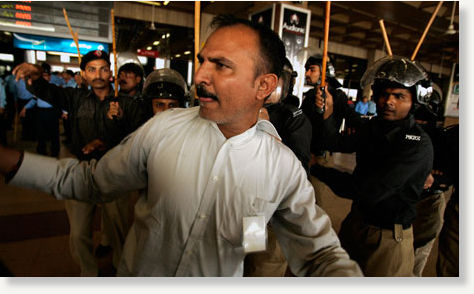

© Shakil Adil/APPolice use batons to disperse protesters at Karachi airport in Pakistan

As Hosni Mubarak reluctantly retired last Friday night, another revolt was reaching its climax in Pakistan. For four days the workers of Pakistan International Airlines (PIA), the national carrier, had been on strike. Some 25,000 passengers were stranded, including me.

I was stuck in Quetta, a tense, paranoid city near the Afghan border where the security forces are engaged in a ruthless cat-and-mouse game with nationalist rebels; it is also a supposed refuge for the one-eyed Taliban leader Mullah Omar. As the skies emptied of planes, guests from my hotel fled Quetta by car, crossing the sprawling deserts, or chancing the rickety 22-hour train ride to Karachi. I stayed put.

On TV the picture flipped from ecstatic crowds surging through Tahrir Square in Cairo, to Pakistani riot police baton-charging PIA workers at Karachi airport. The strike was over planned reforms. PIA is a bloated, sick elephant. It has 400 employees per aircraft - about three times the norm - and last year it asked the government to pay $1.7bn (£1.06bn) in debt. But the unions objected to plans to rationalise the workforce, and demanded that managing director Aijaz Haroon resign. And so on Friday night, under immense pressure, he went, resigning at the same time as Mubarak fell in Egypt.

As the screen filled with ecstatic revolutionaries surging through Tahrir Square, a note of envy sounded among Pakistanis on Twitter. Could the glorious revolution spread to their country? "I wish, wish, wish Pakistan could be next," wrote the author Fatima Bhutto.

Pakistan certainly seems ripe for revolt. It is perpetually on a knife edge - extremists plot and explode bombs, senior politicians are assassinated, society seethes with discontent. A slim upper crust floats in a bubble of wealth and privilege - the local version of Hello! offers coverage of upper-class toddler parties - while the poor grind along under soaring food inflation and 12-hour power cuts. Regional tensions threaten to pull the country asunder. In Quetta, residents were shivering in their homes because the rebels had blown up the gas pipelines four times over the previous week.

"We're in a bad way," one mournful lawyer told me before I left, glancing over his shoulder to see if intelligence officials were evesdropping.

Some analysts compare the mood to Iran in 1979, when a restive middle-class upended the American-backed Shah and opened the door to theocratic Islamic rule. Yet on the ground in Pakistan, the whiff of revolution is faint. For a start, the country is too fractured. Take Karachi, a sprawling megalopolis of 16 million people, about the size of Cairo. Control of the city is divided between a patchwork of political, sectarian and criminal gangs. All are heavily armed. Protests against Pervez Musharraf in the city four years ago pitted rival groups against each other, triggering a bloodbath.

The bigger problem, perhaps, is that there is no dictator to overthrow. Pakistanis already have democracy, elections and a vigorous press. But among the educated classes, few want to engage with the political system, considering it dirty and corrupt. And so they focus their frustration on their president, Asif Ali Zardari, a fantastically unpopular figure. Locked into his fortified Islamabad palace, Zardari is portrayed by a hostile media as aloof and corrupt, a schemer and a shyster. Many people are prepared to believe the most lurid stories about him, including that he plotted the assassination of his wife, Benazir Bhutto, in 2007. Zardari-hating has become a virtual fetish among the chattering classes.

Some of this is warranted - his government disastrously bungled the recent blasphemy furore, and is struggling to deal with the case of Raymond Davis, an American official who shot two people dead on a Lahore street. Corruption is certainly rife, although many of the wilder stories are almost certainly exaggerated. But the hard truth is that power in Pakistan resides inside the gleaming halls of the army headquarters, where liveried generals hold the keys to the country's nuclear weapons - more than 100, according to one recent count - and control policy with India, Afghanistan and America.

And so a true revolution in Pakistan would see the army being ousted from power - except that would be tricky, because it isn't officially in charge.

The real danger, however, may lie in the dark clouds gathering over the economy. Ccompanies such as PIA are sucking the Treasury dry; last week's strike demonstrated scant political will to get them into shape. On the revenue side, the rich refuse to pay tax - the tax-to-GDP ratio is a disastrously low 9% and many politicians pay just a few hundred pounds tax per year. To plug this hole, the government has resorted to printing money at an alarming pace. Few doubt it is unsustainable. Over tea in his office, a senior western diplomat told me the economy was his "number one priority".

Economists say the bubble could burst in a matter of months - rocketing inflation, a crashing currency, capital flight. If that happens, trouble could stir on the streets, notwithstanding Pakistanis' amazing tolerance for adversity. But it's unlikely to have the same clean lines as the Egyptian revolt. And its consequences could be just as unpredictable.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter