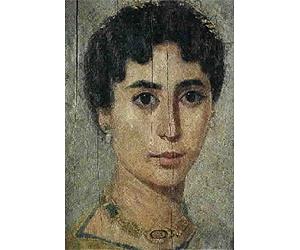

When Hypatia was born, her father, Theon, was a professor of mathematics and astronomy in Alexandria. He believed, as many Greeks did, that it was possible to raise a perfect human being. So he gave his daughter the best possible education, including studies in mathematics, languages, rhetoric, and natural philosophy-or science.

Upper-class women of the time were usually secluded, expected to devote themselves solely to their husband and children, but Hypatia found a job at the most famous institution in the ancient world, the library at Alexandria. She taught mathematics, physics, and astronomy, and wrote many books about these subjects-thirteen books on algebra, her favorite subject, and another eight books on geometry.

She also designed an astrolabe, an instrument used to measure the positions of the stars, another important tool for sailors, which let them locate specific stars and use the stars' positions for navigation. She used her astrolabe to calculate the positions of specific stars, and then published her data in tables. Sailors and astronomers used her tables of positions of the stars, Astronomical Canon, for the next 1200 years.

In her classes and public lectures, Hypatia exhorted people to think critically. "Reserve your right to think," she said. "For even to think wrongly is better than not to think at all."

When Hypatia sided with Orestes, the Roman governor of Egypt, in a power struggle with Cyril, the head of the Christian Church in Alexandria, her enemies decided to silence her. An angry mob, some say sent by Cyril, attacked and murdered her. They beat her with stones, cut her with clam shells, and finally burned her body.

The death of Hypatia, and the loss of the world's largest collection of scientific and mathematic writings, were factors that contributed to the halt of scientific advances in the West halt for nearly a thousand years.

"Astronomy was never just a man's field," Ms. Armstrong says. "Women have always studied the night sky."

Her book Women Astronomers: Reaching for the Stars, which has received critical praise internationally, examines the remarkable accomplishments of 21 women who struggled with society's narrow ideas on the appropriate roles for women and the incredible challenges each met in her own way.

She describes the stories of some of the fascinating women who dared to look toward the stars-from the earliest known woman astronomers, to Hypatia of Alexandria, to Astronaut Sally Ride and all the fascinating, brave women in between.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter