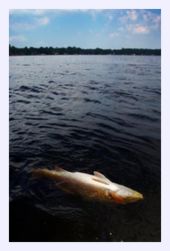

If you think the month-long fish kill on the St. Johns River is an annual event that just came early this year - think again.

That's the message that two men with close ties to the river want you to know.

The persistent plague of dead fish on the St. Johns that began around Memorial Day isn't caused by a cycle of summer oxygen depletion, insists Jimmy Orth, the executive director of the St. Johns Riverkeeper.

"This kill is unprecedented," he said. He explained that fish kills due to low oxygen levels are typically confined to smaller areas, not as widespread as the problem has become.

Fish continue to die in an area from roughly the Buckman Bridge south to Lake George - where the algal bloom is the worst.

Liz Miller, environmental manager of the Florida Department of Environmental Protection, said in an e-mail last week that dissolved oxygen is monitored by the St. Johns River Water Management District throughout the river - from Lake George to two miles north of Palatka.

"Monitoring at these stations has not indicated any D.O. [dissolved oxygen] crashes" at those sites, she said.

As of Thursday, the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission's Fish Kill Hotline had received 290 calls regarding the St. Johns River. Catalina Brown, who oversees the hotline, said the frequency of calls is slowing. But Orth counters that the number of dead and dying fish is not diminishing - only the phone calls.

"Most people will call once, not every time they see a dead fish."

Quinton White, the executive director of the marine science institute at Jacksonville University, said that an algal bloom called aphanizomenon has been identified in the river. The more common blue-green algae are microcystis. He said that the former appears to be more numerous in the river this year.

That bloom, he says, is a tricky one. It can release several types of toxins - or no toxins - depending on a myriad of environmental conditions in the river.

The FWC's lab in St. Petersburg received fresh, dead fish immediately after the fish kill became apparent. At that time, biologists said it would take up to three weeks for tissue samples to be checked for toxins. At mid-week, Brown said that her understanding was that the samples would be ready next week, at which time evaluation would begin.

White said the timetable is understandable.

"This isn't CSI [the television show] where DNA samples are done in minutes. ... These things take time ... scientists are being scientists," White said. He said the lab is also being inundated with sampling from the Gulf oil spill.

White said that last week the St. Pete lab sent staff to Jacksonville University to sample more recently killed fish. "They did necropsies on site," he said.

He said they found lesions in the brains of some redfish. "I'm not sure what else," White said.

That, White says, points to toxicity. He said his best guess - without the tissue sampling data - is that the toxin is acting like a hemorrhagic poison, much like spider and snake venoms.

"The blood is the transport system for it," said.

White said that he's received reports from the area of the Rudder Club - adjacent to the Buckman Bridge - of water birds that mainly eat small fish regurgitating stomach contents.

He said more hardy fish are dying - such as redfish, gars and skates - because they're more the apex predators in the river. Toxins would be more likely to build up in their systems.

Ciguatera poisoning is an example of this ,and is usually found in larger barracuda. The toxin, in that case, are produced by dinoflagellates that typically grow on marine algae. Little fish eat the algae; bigger fish eat them, and so on. The higher up the food chain you go, the more the toxin can accumulate in the fatty tissue of the fish.

A major difference, however, is that Ciguatera toxin does not seem to harm the fish, only the humans eating it.

Regardless of the results of the tissue sampling, White said that the prognosis isn't something the public is going to want to hear.

"There will be no quick or easy solution" to whatever is happening. Identifying the problem isn't likely to make it go away.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter