© 20th Century FoxNetworked life is not just sci-fi

In the movie

Avatar, the Na'vi people of Pandora plug themselves into a network that links all elements of the biosphere, from phosphorescent plants to pterodactyl-like birds. It turns out that Pandora's interconnected ecosystem may have a parallel back on Earth: sulphur-eating bacteria that live in muddy sediments beneath the sea floor.

Some researchers believe that bacteria in ocean sediments are connected by a network of microbial nanowires. These fine protein filaments could shuttle electrons back and forth, allowing communities of bacteria to act as one super-organism. Now Lars Peter Nielsen of Aarhus University in Denmark and his team have found tantalising evidence to support this controversial theory.

"The discovery has been almost magic," says Nielsen. "It goes against everything we have learned so far. Micro-organisms can live in electric symbiosis across great distances. Our understanding of what their life is like, what they can and can't do - these are all things we have to think of in a different way now."

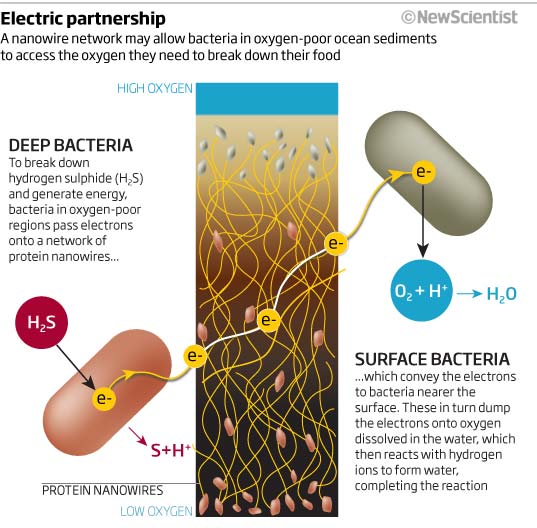

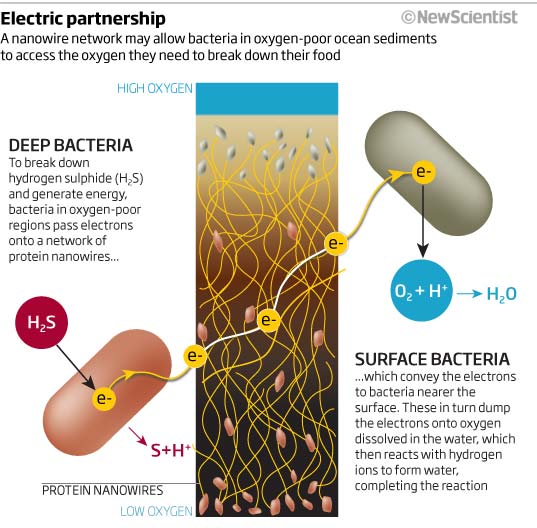

Many marine bacteria generate energy by oxidising the gas hydrogen sulphide, which is common in ocean sediments. To do this, the bugs need access to the oxygen in seawater to carry away the electrons produced as the sulphide is broken down.

Nielsen and his team took samples of bacteria-laced sediment from the sea floor close to Aarhus. In the lab, they first removed and then replaced the oxygen in the seawater above the samples. To their surprise, measurements of hydrogen sulphide revealed that bacteria several centimetres from the surface started breaking down the gas long before the reintroduced oxygen had diffused down to them (

Nature, DOI:

link).

© New Scientist

Nielsen believes a network of conductive protein wires between the bacteria makes this possible, allowing the oxidation reaction to happen remotely from the oxygen that sustains it. The wires transport electrons from bacteria in deeper, oxygen-poor sediments to bacteria in oxygen-rich mud near the surface. There, they are offloaded onto the oxygen, completing the reaction. Nielsen calls the process "electrical symbiosis".

Other evidence backs up this idea. For years, geochemists have known that microbes generate a weak current in the seabed - a process several groups are using to build microbial fuel cells. "But people have been focused on making power. They've left behind the question of what's going on in nature and why bacteria might have this ability to exchange electrons," says Nielsen.

"These are very encouraging and exciting results," says biogeochemist Yuri Gorby of the J. Craig Venter Institute in San Diego, California. He adds that while Nielsen's results are "highly suggestive" of electrical symbiosis, "we must be careful not to extend conclusions beyond what are scientifically proven". Nanowires have been spotted in the lab by Gorby and other teams, but not in natural sediment. Nielsen, who plans to search for the wires in natural settings, says it is needle-in-a-haystack work.

As for the

Avatar similarities, Nielsen says "we have no indication that more advanced information is exchanged in the network", but admits the parallels are striking.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter