The nearly 600km-wide rock is an example of an object that started out on the process of becoming a planet but never grew up into the real thing.

Researchers have published a 3D model of the grapefruit-shaped mini-world in Science magazine.

Hubble's data makes it possible to discern surface features, including what appears to be a big impact crater.

The new information is expected to help scientists better understand how planets evolve in their earliest phases.

"Pallas is a unique piece of the puzzle of how our Solar System formed," said Britney Schmidt, of the University of California, Los Angeles, who led the observations.

Layering Process

Pallas resides some 400 million km from the Sun, in between the orbits of Mars and Jupiter.

It was the second object discovered in the main asteroid belt (hence the name, 2 Pallas), in 1802.

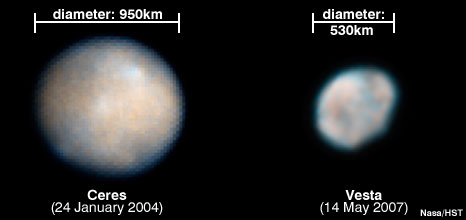

Only Ceres is wider (950km diameter). Another asteroid, Vesta, has a narrower girth but is more massive than Pallas.

Found by Heinrich Olbers in 1802, initially thought to be a true planet, now classed as a B-type asteroid, may have a major impact crater.

Theory holds that planets grow from aggregations of the dust and rock found circling new-born stars.

Collisions between clumps of material produce progressively bigger objects.

Eventually, a few will become large enough, and hot enough, to start to undergo differentiation - a process of layering in which the densest materials move to the centre of the object to form a core.

In the case of Pallas, this process appears to have initiated, but its slightly irregular shape suggests it never quite moved to completion.

"Whether you could form a core is something we can't really determine with these observations, but Pallas is big enough and round enough that it's very possible that its interior started to separate out," Ms Schmidt told BBC News.

"Ceres is perfectly round and so there's a really good chance that that happened. For Pallas, it may be just that this process got started but never finished."

Wet History

Dark features in the Hubble pictures indicate the presence of hydrated minerals on the surface of the asteroid.

If Pallas formed early in the asteroid belt, it would probably have incorporated large quantities of water-ice.

As the rock heated up, this water would have melted. Not only would this have aided differentiation but it also would have altered the silicate rock to produce the type of mineralogical signal obvious today.

It was highly unlikely, though, that Pallas got hot enough to melt silicate rock, said the California researcher.

The presence even now of a lot of water-ice in the asteroid might help to explain its relatively low density (2,400-2,800kg per cubic metre), she added.

The Science paper describing the Hubble observations includes a 3D representation of Pallas. This was built up from a series of snapshots of the asteroid's outline as it rotated in the view of the telescope.

It reveals an intriguing depression in the southern hemisphere which Schmidt's team interprets as a possible impact crater. It is large - about 240km across. It is also near dark terrain which could be material ejected or altered by a collision.

Pallas is known to share orbital characteristics with a group of rocks that could have been blown off the asteroid. The largest of this "family" is called Ioffe and has a diameter of 22km. It is entirely possible Ioffe originated in the assumed crater.

Nasa has sent a spacecraft to the asteroid belt to visit Ceres and Vesta. The Dawn probe will arrive first at the smaller of the two objects in 2011.

Pallas, unfortunately, is not on the itinerary.

But Britney Schmidt believes interest in the asteroids and what they represent can only grow and is hopeful that her protoplanet could one day become a target for a space mission.

"We are really changing our perspective on these objects. When you say asteroid people don't tend to think of big, dynamic, evolved bodies; but that's probably what we have in the case of [Ceres, Vesta and Pallas].

"I'm trying to evolve people's thinking, taking them from 'big rocks to little planets'.

"It's also timely, with public discussion about Pluto and what makes - or doesn't make - a planet. The public are so interested in that."

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter