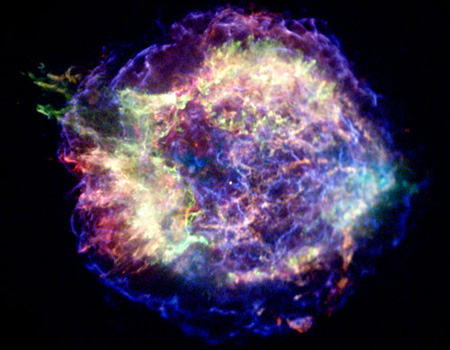

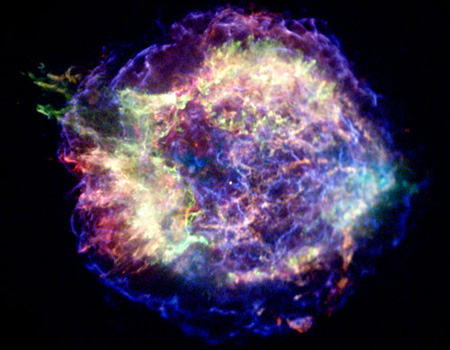

© NASAThe supernova remant Cassiopeia-A.

As astronomers have long expected, exploding stars called supernovas can accelerate particles up to almost the speed of light, a new study shows.

The discovery helps explain where the extremely energetic cosmic rays we find near Earth come from.

Cosmic rays are charged particles, mostly protons, that come swooping through space from beyond the solar system. They carry such an energetic punch they can knock out electronics systems on Earth if they manage to make it past our atmosphere.

Until now, scientists couldn't be sure how cosmic rays acquire their energy and speed.

"It has long been thought that the super-accelerators that produce these cosmic rays in the Milky Way are the expanding envelopes created by exploded stars, but our observations reveal the smoking gun that proves it," said Eveline Helder of the Astronomical Institute Utrecht of Utrecht University in the Netherlands, leader of the new study.

When a star dies in a supernova, the blast releases a huge amount of energy. Much of that energy is used to heat up a bubble of gas that expands around the remnant of the star. Some energy, though, goes toward speeding up the particles that become cosmic rays, the researchers determined.

"When a star explodes in what we call a supernova a large part of the explosion energy is used for accelerating some particles up to extremely high energies," Helder said. "The energy that is used for particle acceleration is at the expense of heating the gas, which is therefore much colder than theory predicts."

Helder and team looked at the leftovers from a supernova called RCW 86 with the European Southern Observatory's Very Large Telescope. The star exploded about 8200 light-years away in AD 185, and was recorded by Chinese astronomers.

The modern researchers measured the temperature and speed of the gas behind the shock wave created by the stellar explosion. They found that the gas, at 54 million degrees Fahrenheit (30 million degrees Celsius), was much lower than would be expected given the shock wave's velocity.

Rather than heat up the gas, some of the supernova's energy went toward speeding up particles to near the velocity of light, the astronomers concluded.

"The missing energy is what drives the cosmic rays," said collaborator Jacco Vink, also from the Astronomical Institute Utrecht.

Helder and team describe their findings in the June 26 issue of the journal

Science.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter