© Unknown

Do we all have the capacity for synaesthesia or is the brain's ability to blend senses bestowed on a select few at birth? It now seems it could be a mixture of the two.

Synaesthesia seems to underpin some savants' enhanced memory and numerical skills. The hope is that a better understanding of its origins could help to explain savant abilities - and perhaps even shine some light on whether we are all capable of attaining them.

The condition is thought to arise when extra connections in the brain cross between regions responsible for separate senses. To see if genes play a role in building or maintaining these connections, a team led by Julian Asher at the University of Oxford took genetic samples from 196 individuals from 43 families, 121 of whom exhibited auditory-visual synaesthesia, meaning they "see" sounds. "When I hear a violin, I see something like a rich red wine," says Asher, who is a synaesthete. "A cello is more like honey."

From their analysis, the team were able to pin down four chromosomal regions where gene variations seemed to be linked to the condition (

The American Journal of Human Genetics, DOI:

link). As one of the regions has also been associated with autism, there may be a common genetic mechanism underlying the two, says Asher.

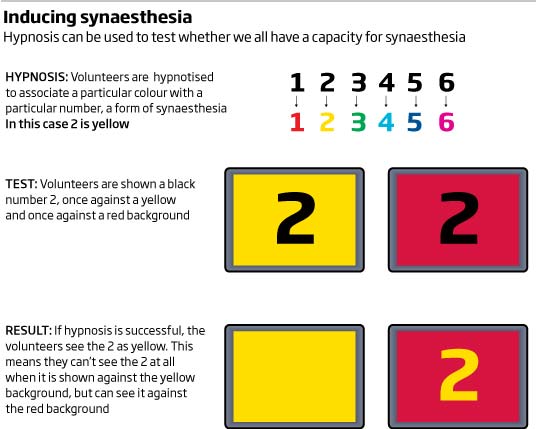

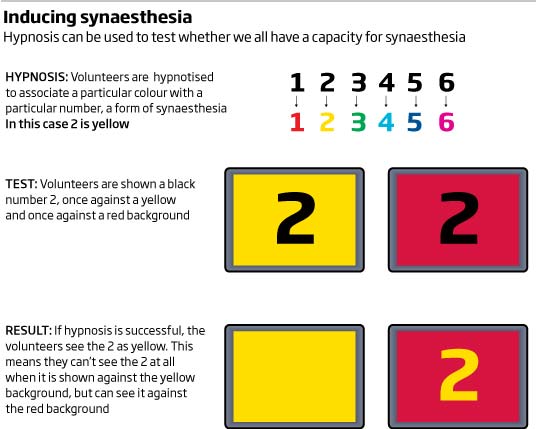

So if we are genetically disposed to develop synaesthesia, does that rule out the possibility of inducing the experience? To find out, Roi Cohen Kadosh from Imperial College London and colleagues hypnotised four volunteers so that they viewed numbers as having innate colours, known as grapheme-colour synaesthesia. The volunteers then looked at a series of coloured slides, some with a black digit in the centre and some without.

Like people with synaesthesia, roughly 80 per cent of the time the hypnotised volunteers failed to see the digits when the background colour corresponded to the colour they associated with a number. Controls who had not been placed under a trance, but were instructed to attach a colour to each number, did not make this mistake (

Psychological Science, DOI:

link).]

"It shows that even without hyperconnectivity in the brain, you can still have synaesthesia," says Cohen Kadosh. He says hypnosis may reactivate connections that had been suppressed by the brain.

Julia Simner from the University of Edinburgh, UK, has further evidence that synaesthesia is not the result of neural connections fixed before birth. She studied 615 6 to 7-year-olds, eight of whom turned out to be grapheme-colour synaesthetes. Over the course of a year, these children gradually associated more letters with colours, showing that the ability developed with time (

Brain, DOI:

link).

So should we all attempt to develop savant-like abilities? "Synaesthesia is strongly linked to improved memory capabilities so it would definitely be a good thing to research," says Simner. Asher is more cautious, stressing that synaesthesia is often distracting, for example, while reading or listening to a lecture. He hopes to develop a genetic test to diagnose children and warn teachers of potential difficulties.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter