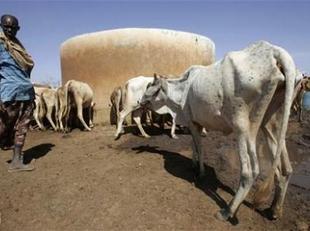

Waregadud - Clouds of dust rising above the harsh scrub herald the arrival of more livestock at a borehole in northeastern Kenya, the end for some of a 45-km (28-mile) trek for water that must be repeated every few days.

Drought is starting to bite in east Africa's biggest economy and the government has declared a state of emergency, saying 10 million people may face hunger and starvation after a poor harvest, crop failure, a lack of rain and rising food prices.

For an economy still recovering from post-election violence last year and facing fallout from the global slowdown on export markets, Kenya's looming food crisis risks putting more pressure on its fragile coalition government.

Kenyans have been horrified by multi-million dollar government graft scandals in the maize and fuel sectors in the middle of the food shortage, and at a time when the administration is appealing for international food aid.

The Kenya Food Security Meeting (KFSM), a coordinating body of government ministries and non-governmental organizations, said last month food security was critical for 3.7 million people, including half a million schoolchildren.

"High food and non-food prices, livestock disease, crop failure and conflict have compounded already precarious food insecurity," the KFSM said in its January update.

It said rains at the end of 2008 were generally poor after three successive poor seasons. In the area around Waregadud in Mandera, rainfall was just 10 to 20 percent of normal levels in the October-December period.

The Mandera region bordering Ethiopia and Somalia -- like much of Kenya -- is prone to drought. The lack of rain has left dams dry, pasture is dwindling and herders say tension is rising as animals and humans compete for resources.

SKIPPING MEALS

Abduallahi Abdi, head of the village council that manages the borehole at Waregadud, worries that children are becoming malnourished because of a persistently poor diet.

"We are skipping meals. We eat just one meal at night," he said. "In the next few weeks, things are likely to become serious as we are already in a dire situation."

"If we don't get assistance before then we will start getting human deaths," Abdi said. "It is shameful to ask for help -- we do it with a lot of reservations -- but when things are out of hand we have no choice."

The problem Kenya and neighboring drought-prone countries in the Horn of Africa face is that traditional donors struggling with economic crisis are not meeting aid demands.

Aid workers say, while drought is a regular feature here, this time the crisis has been compounded by high food and fuel prices worldwide, and in Kenya by post-election violence that meant farmers in the fertile Rift Valley failed to plant crops.

The International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies (IFRC) launched an appeal for $95 million in December to help those at risk of starvation in the Horn of Africa, but it says pledges so far have met just 6 percent of the appeal.

"When the governments of the world are busy bailing out car companies ... it's a shame that for a fraction of that they can't intervene to save millions," said Andrei Engstrand-Neacsu, IFRC communications officer for east Africa.

In the hamlet of Qalanqlesa in Mandera, a sprawl of traditional huts in a stark landscape of dust and grey, leafless trees, village chairman Aden Hassan says herders trekked 55 km (34 miles) in search of pasture but were turned back by other pastoralists.

They have a small borehole nearby but the quest for water has doubled the size of the village since December and they have started to ration the precious commodity.

"Competition for scarce resources is becoming acute ... there is a lot of friction," Hassan said.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter