The falls in numbers are so sharp and widespread that ornithologists are waking up to a major new environmental problem - the possibility that the whole system of bird migration between Africa and Europe is running into trouble.

|

| ©Independent Graphics |

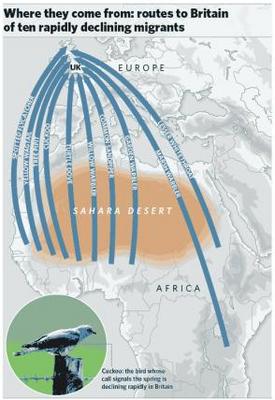

It is estimated that, each spring, 16 million birds of nearly 50 species pour into Britain to breed from their African winter quarters, and as many as five billion into Europe as a whole, before returning south in the autumn. Many are songbirds weighing next to nothing, and their journeys of thousands of miles, including crossing the Sahara desert each way, have long been recognised as one of the world's most magnificent natural phenomena on the scale of the Gulf Stream or the Indian monsoon. But now their numbers are tumbling precipitately.

Well-loved migrants such as the spotted flycatcher, the garden warbler and the turtle dove are increasingly failing to reappear in the spring in places where they have long been familiar. Across Britain, many people who used to look forward each year to hearing the first cuckoo - just about now, in the third week of April - no longer have the chance to do so. If fewer and fewer birds are returning to their breeding grounds, the inevitable consequence is that their populations will shrink ever more rapidly, ultimately, towards extinction. That may still be a long way off for the global populations of many migrants, but in Britain, several species are heading towards disappearance.

This worrying prospect is outlined in the first full statistical account put together by experts seeking to understand what is happening and why. Figures in an unpublished survey produced by the Royal Society for the Protection of Birds paints a startling picture of plunging populations. Of the 36 British-African migrant species for which there is long-term population data (going back to 1967), 21 have declined significantly.

These include the two species which have become extinct in Britain in the same period - the red-backed shrike and the wryneck, the only migratory woodpecker - and another 11 which have suffered declines of more than 50 per cent.

This "50 per cent plus" group includes both the willow warbler and the cuckoo, with declines of 60 and 59 per cent, while at the top end of the scale, the spotted flycatcher, the tree pipit and the turtle dove have suffered declines of 84, 83 and 82 per cent respectively. For the 42 migrants for which there are short-term population trends available (going back only to 1995), 23 have declined - 55 per cent of the total. This includes a 30 per cent decline of the cuckoo, a 43 per cent decline of the pied flycatcher, and a 60 per cent decline of the wood warbler, just in the past 13 years.

The study, compiled by the RSPB research biologist Steven Ewing and likely to be published later this year, goes on to show that this pattern is not confined to Britain. It is being repeated across Europe as a whole, from Spain to Finland, with 27 out of 37 European-African migratory species for which there is reliable long-term population data - 72 per cent of the total - undergoing declines.

These include species such as the nightingale, which is showing one of the severest declines with a 63 per cent drop in numbers across Europe between 1980 and 2005.

In Britain, the nightingale is now such a rare bird that it is not picked up in standard monitoring schemes, meaning there is no reliable population data for the species. But there is no doubt that it is also declining here.

No one knows the reasons for these disappearances, which may be many and complex, although theories being discussed include habitat degradation in Africa and climate change. But they are pointing firmly to the possibility that, after millions of years the Afro-European bird migration system is going fundamentally wrong. The problem may be on the birds' journeys, which are full of hazards, or on their wintering grounds south of the Sahara. Ornithologists from all over Europe will meet in Germany next month to discuss both the vanishing migrants, and the possibility of setting up a network of research stations in Africa to investigate what is happening.

The meeting, at the Radolfzell bird observatory on Lake Constance, has been organised by two scientists, Volker Salewski from Radolfzell and Will Cresswell from the University of St Andrews. "With a large number of our migrant species which are suffering declines, you don't have to look all that far into the future for when the lines on the graph cross zero," Dr Cresswell said. In Britain, the RSPB and the British Trust for Ornithology are switching their attention from farmland birds, whose declines because of intensive agriculture have long been a major concern, to focus on the startling fall-off in migratory bird numbers. Both are actively planning new research programmes concentrating on migrants.

"We are seeing some very marked declines in migrants, which are giving us real cause for concern," said Dr David Gibbons, the RSPB's head of conservation science. "These birds form a huge part of our native avifauna and we need to help them before they disappear from the British and European countryside."

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter