|

| ©Bernhard Steinberger

|

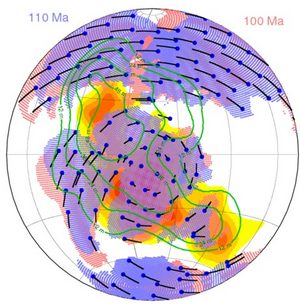

| An illustration shows what Earth's continents looked like 110 million to 100 million years ago and their rotation based on magnetic signatures in ancient rocks. A new study suggests that the motion represents a phenomenon called true polar wander, in which Earth's landmasses become imbalanced compared to its spin axis and then move rapidly to right themselves.

|

A new study lends weight to the controversial theory that Earth became massively imbalanced in the distant past, sending its tectonic plates on a mad dash to even things out.

Bernhard Steinberger and Trond Torsvik, of the Geological Survey of Norway, analyzed rock samples dating back 320 million years to hunt for clues in Earth's magnetic field about the history of plate motions.

The researchers found evidence of a steady northward continental motion and, during certain time intervals, clockwise and counterclockwise rotations.

That pattern matches the predictions of a phenomenon known as true polar wander, a theory first proposed in the 1950s.

The theory states that at times Earth's surface mass becomes imbalanced. The continents become dramatically offset from the planet's spin axis and so move rapidly to right themselves.

The new study shows evidence for such motion within the past 320 million years that would have been enough to shift the continents by about 18 degrees latitude.

A change like that today would put Richmond, Virginia, where Mexico City is now. (See a map of the region.)

Island Hot Spots"I am surprised that our results clearly indicate those episodes of true polar wander at all," Steinberger said.

"Up until now, there wasn't really any agreement in the community about the existence and amount of true polar wander."

That's because the phenomenon has been difficult to distinguish from the slower motion of tectonic plates traveling over the underlying mantle, Steinberger said.

Scientists often use hot spots, relatively fixed thermal plumes of material that rise up from the deep mantle, to track the paths of plates. The Hawaiian island chain is thought to be an example of a hot spot.

But geological records of suitable hot spot chains only go back about 130 million years.

A convergence of improvements to geologists' tools paved the way for the team to probe further back in time, Steinberger said.

"We use an updated global plate-tectonic reconstruction and integrate suitable paleomagnetic results from all continents," he said.

The authors were then able to compute the global average of continental motion and rotation as far back as 320 million years ago.

Paleomagnetic records like the ones used in the study can provide a new reference frame for relating surface motions to deep-mantle processes, the authors say.

The study appeared in last week's issue of the journal

Nature, and another paper elaborating on the results is in press with Reviews of Geophysics.

Same on Mars?Given current understanding of Earth's geology, Steinberger is puzzled that true polar wander doesn't show up more often in the planet's history.

"It points toward a long-term stability ... which is not expected from fluid dynamics, something which currently geodynamicists try to understand."

Papers published in the journal

Science in 1997 and 1998 proposed a much more dramatic polar wander associated with the Cambrian Explosion, a huge diversification in species that shows up in the fossil record beginning around 550 million years ago.

Co-authors of those studies suggested that Earth's continents were thrown asunder relative to the planet's spin axis by about 90 degrees at the time.

One of the researchers, Joseph Kirschvink of the California Institute of Technology, theorized that the shift happened after one or more major subduction zones in the ancient oceans closed down during the final assembly stages of the supercontinent Gondwanaland.

That sent the entire continent rotating at almost a right angle beginning about 534 million years ago, said the authors of the earlier work.

About 16 million years later, North America darted from deep in the Southern Hemisphere to the Equator.

"Even the type of marine rocks deposited on the various continents - carbonates in the tropics, and clays and clastics in high latitudes - agree with these paleomagnetically determined motions," Kirschvink notes on his Web site.

Kirschvink's co-author David Evans, now an associate professor of geology at Yale University, said he's most excited about a relationship between the latest paper and one that came out in

Nature last year.

The 2007 study proposes similar continental shake-ups on Mars.

"In the geosciences, we as a community have continued to be impressed by the differences among all the terrestrial planets," he said.

But when it comes to polar wander, Earth and Mars might not be so far apart.

Evans said large igneous regions on both planets - Tharsis on Mars and the central Atlantic magmatic province on Earth - were so massive that they threw their host planets off balance in the distant past.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter