The extinction of the dinosaurs 65 million years ago can be traced to a collision between two monster rocks in the asteroid belt nearly 100 million years earlier, scientists report on Wednesday.

|

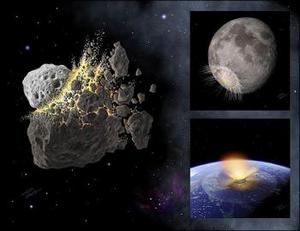

| ©Southwest Research Institute

|

| Computer modeling shows that the parent object of asteroid (298) Baptistina, which was approximately 170-kilometres in diameter with characteristics similar to carbonaceous chondrite meteorites, was disrupted 160 million years ago when it was hit by another asteroid estimated to be 60-kilometres in diameter (L) .The extinction of the dinosaurs 65 million years ago can be traced to a collision between two monster rocks in the asteroid belt nearly 100 million years earlier, scientists report. The two pictures on the right show remnants of the collision impacting the Earth and Moon. Image obtained from Southwest Research Institute.

|

The smash drove a giant sliver of rock into Earth's path, eventually causing the climate-changing impact that ended the reign of the dinosaurs and enabled the rise of mammals -- including, eventually, us.

Other asteroid fragments smashed into the Moon, Venus and Mars, pocking their faces with mighty craters, the US and Czech researchers believe.

Mixing skills in time travel, jigsaw-making and carbon chemistry, the trio carried out a computer simulation of the jostling among orbital rubble left from the building of the Solar System.

The sleuths were guided by an intriguing clue -- a large asteroid called (298) Baptistina, which shares the same orbital track as a group of smaller rocks.

Turning the clock back, the simulation found that the Baptistina bits not only fitted together, they were also remnants of a giant parent asteroid, around 170 kilometers (105 miles) across, that once cruised the innermost region of the asteroid belt.

Around 160 million years ago -- the best bet in a range of 140-190 million years -- this behemoth was whacked by another giant some 60 kms (37 miles) across.

From this soundless collision was born a huge cluster of rocks, including 300 bodies larger than 10 kms (six miles) and 140,000 bodies larger than one kilometer (0.6 of a mile).

Over aeons, the fragments found new orbits with the help of something called the Yarkovsky effect, in which thermal photons from the Sun give a tiny yet inexorable push to orbiting rocks.

As the family gradually split up, a large number of chunks -- perhaps one in five of the bigger ones -- crept their way out of the asteroid belt and became ensnared by the gravitional pull of the inner planets.

Around 65 million years ago, a 10-km (six mile) piece crunched into Earth, unleashing a firestorm and kicking up clouds of dust that filtered out sunlight.

In this enduring winter, much vegetation was wiped out and the species that depended on them also became extinct. Only those animals that could cope with the new challenge, or could exploit an environmental niche, survived.

The trace of the great event, called the Cretaceous/Tertiary Mass Extinction, can be seen today in the shape of a 180-km (112-mile) -diameter impact crater at modern-day Chicxulub, in Mexico's Yucatan peninsula.

The trio of researchers -- William Bottke, David Vokrouhlicky and David Nesvorny of Southwest Research Institute in Colorado -- took their theory a stage further and checked out sediment samples from the Chicxulub site.

They found traces of a mineral called carbonaceous chondrite, which is only found in a tiny minority of meteorites, as the earthly remains of plummeting asteroids are called. Most asteroids can be excluded from the Chicxulub event, but not Baptistina-era ones, they contend.

Putting simulation and chemical evidence together, the team rule out theories that a comet was to blame rather than an asteroid, and say there is a "more than 90 percent" probability that the killer rock was a refugee from the Baptistina family.

The investigators also put a 70-percent probability that a four-km (2.5-mile) Baptistina asteroid hit the Moon some around 108 million years ago, forming the 85-km (52-mile) crater Tycho.

The probability is lower than for Chicxulub because it is based only on a simulation.

The peak of "Baptistina bombardment" was probably around 100 million years ago but is not over yet, the paper cautions.

Many of the asteroids that skim dangerously close to Earth today owe their orbits to that great collision in the deep past, according to the authors.

"We are in the tail end of this shower now," says Bottke. "Our simulations suggest that about 20 percent of the present-day near-Earth asteroid population can be traced back to the Baptistina family."

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter