|

| ©Ja-Young Kim/Dave Gresham |

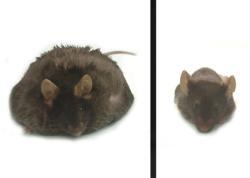

| A mouse (pictured on the left) engineered to overproduce the hormone adiponectin weighs 100 grammes - five times as much as a normal mouse (pictured on the right) |

Philipp Scherer at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center in Dallas, Texas, US, and his colleagues studied mice that had been genetically engineered to overeat. The mice gorged on food because they lacked the ability to produce an important appetite-suppressing hormone called leptin.

The researchers then bred a subgroup of these leptin-deficient mice to overproduce another key hormone that gets released by fat cells, called adiponectin, by about threefold. Under normal circumstances, an increase in adiponectin levels signals that an animal has entered "starvation mode" because it has not eaten for some time.

All of the leptin-deficient mice ate non-stop, but those bred to overproduce adiponectin packed on almost twice as much weight by the end of the 20-week experiment.

Location, location, location

Whereas a normal, healthy mouse weighs about 20 grammes, the mice lacking leptin weighed roughly 60 grammes. The adiponectin over-producers weighed about 100 grammes.

"It's probably the most obese mouse that's ever been reported," Scherer says of their particular mouse strain.

Interestingly, none of the rodents that made extra adiponectin developed symptoms of diabetes, such as high blood sugar. By comparison, all of the other leptin-deficient mice developed this disease during the course of the experiment.

When Scherer and his team examined the distribution of body fat within the mice, they found that the obese rodents with an abundance of adiponectin had a great deal of fat stored under the skin, but very little fat within organs such as the liver.

This unusual allocation of fat might explain why the animals remained in good health - extra fat in the liver can make the organ less sensitive to insulin, thereby leading to diabetes.

Scherer firmly believes that the distribution of fat can make all the difference in terms of whether obesity will lead to diabetes. "It's a little bit like real estate; it's location, location, location."

Sudden death

Adiponectin appears to help the body store fat under the skin by increasing the number of fat cells there.

Notably, in the weeks following the formal end of the experiment, about 10% of the mice that overproduced adiponectin experienced sudden death. But this was due to the fact that their vital organs stopped functioning under the crushing weight of their fat, not because of a particular disease.

Some of the 100-gramme mice also developed enlarged hearts, which in humans can predispose people to heart failure.

The new findings might lead to new ways of treating diabetes in the future, says Scherer. He notes that many drugs currently used to treat diabetes lead to an increase in adiponectin levels in patients.

Scherer says that giving adiponectin itself would not work well since the protein gets broken down very quickly in the body. But he adds that scientists might want to look for compounds that can act directly on the adiponectin signalling pathway to migrate fat out of the liver of obese patients.

Journal reference: Journal of Clinical Investigation (DOI: 10.1172/JCI31021)

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter