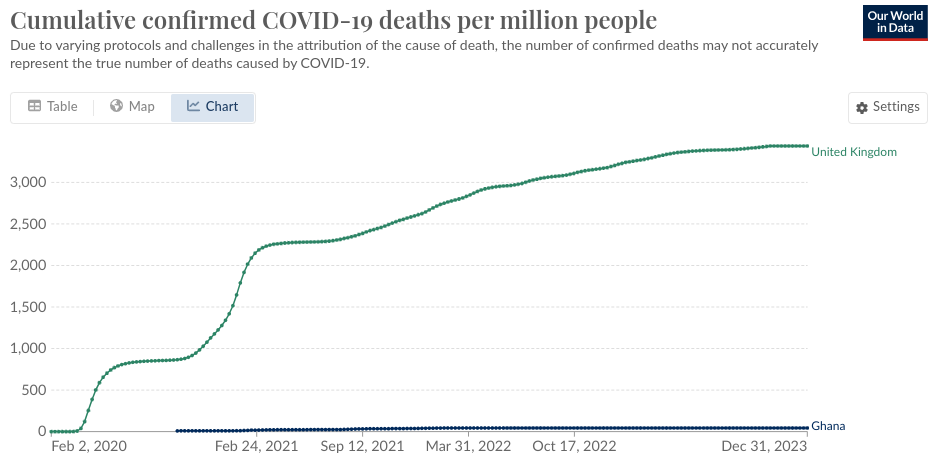

Dr. Duch, a Director of the Centre for Experimental Social Sciences at Nuffield College, Oxford, writing in collaboration with Professor Philip Clarke, an economist of the Nuffield Department of Population Health, says that their trial of this measure in Ghana (yes, they actually got ethical approval to try it out - now published in Nature) proves that it works. By works they mean that yes, some poorer people will offer you their arm if you offer them hard cash - in this case an amount equivalent to around 15% of the weekly food bill, which is $3 is Ghana and may be around $14 in the U.S. But by 'works' they don't mean that it successfully reduces Covid deaths or illness. They didn't look at that. And since Ghana had almost zero confirmed Covid deaths, we can assume the (positive) impact of vaccination in the country was non-existent (even allowing that official Covid deaths may be under-counted).

"Some will ask whether paying people to adopt good health behaviours is a desirable route to take," writes Dr. Duch. Well, quite. Ethical strictures around informed consent usually forbid any form of inducement to take drugs or undertake medical procedures (except in an acknowledged experimental context such as a clinical trial). But this isn't what Dr. Duch means. He means, will it reduce vaccine take-up in the long run. "Supplementing social norms with cash could erode the public's commitment to complying with important health campaigns." But not to worry: it all looks good on that front: "Our Ghana trial explored the effect of the scheme on individuals who did not receive cash for vaccines. Consistent with another recent trial in Sweden, our results showed no negative effect on vaccination levels."

Vaccine take-up is the only metric Dr. Duch regards as of any significance, apparently.

Yet the trial was hardly a runaway success, even by these narrow lights. The payment group only had 9% higher take-up than the non-payment group - practically a rounding error. This was in February 2022, too, when Omicron was running wild, though perhaps the well-known lower fatality rate reduced demand. It seems most people aren't willing to sell you their personal medical decision-making, even if they do live in a developing country.

But since Dr. Duch seems to regard this as a way of reaching a 70% vaccination rate (he doesn't explain why 70% is desirable; perhaps he is still operating under the discredited assumption that this will stop the spread of the virus) he presumably sees it as proof of concept. Simply increase the pay and more people will come forward, is maybe his logic. If so, I suspect he would be disappointed in this. He writes:

The international community spent more than $20bn supporting COVID-19 vaccination campaigns in low- and middle-income countries. It was one of the costliest public health initiatives ever targeted at these nations. Despite this, Africa trailed behind the rest of the world in terms of vaccination rates: a more equitable global pattern of jabs would have prevented the loss of hundreds of thousands of lives. And incentivising vaccination with cash would have saved many of them.Frankly, I find it hard to understand how this study gained ethical approval. Maybe it helped that it was in Ghana; I doubt it would have been allowed in the U.K. It must also have helped that it was an economics study, not a medical one. According to the methods section of the paper it had ethical oversight from the University of Oxford Economics Department. I don't suppose that department is overflowing with expertise in medical ethics.

Actually, there is one other metric Dr. Duch recognises.

But simply giving cash to some of the poorest individuals in the world, even ignoring the public health benefits, would have positive outcomes. In our trial the effective $3 cash incentive represented about 15% of weekly food expenditures. Scaled up to national levels this would have represented an important economic boost during a severe negative economic shock. In Ghana, for example, a $3 financial incentive would have injected $70m directly into the hands of consumers if vaccination rates reached the goal of 70%.Vaccination boost and economic boost: what's not to like?

"The wake of the pandemic is a good time to reflect on how to best navigate global public health challenges when they arise in future," concludes Dr. Duch. "Small cash incentives to promote uptake could be a game-changer."

The comments, even in the very mainstream FT, were universally negative beneath this article, which was a relief. "This is so unethical it makes me puke," says the top-rated comment. I couldn't put it better myself.

I wouldn't be too sure of that.