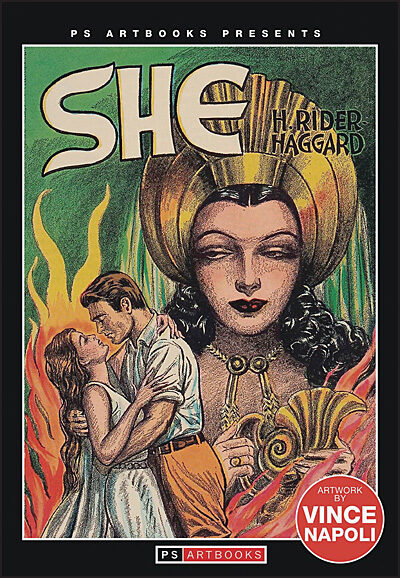

"If this don't fetch the kids, why, they have gone rotten since my day."In 1887, H. Rider Haggard wrote a novel called She. She was an adventure into deepest Africa to rediscover a lost civilization dominated by a mysterious white goddess. The novel was an immediate success and a phenomenon at all levels of society. Freud and Jung referenced it in their psychoanalytic theories. Authors such as Rudyard Kipling, J.R.R. Tolkien, Graham Greene, and Henry Miller have acknowledged its influence on their own writing. The novel even developed many of the 'lost world' tropes that underlie the works of Edgar Rice Burroughs, Arthur Conan Doyle, H.P. Lovecraft, Robert Howard, and Abraham Merritt. Everyone, in other words, read She. Yet Haggard said he wrote it for boys.

— Robert Louis Stevenson, while writing 'Treasure Island'

Haggard isn't the only writer who wrote similar boys' adventure stories. Robert Louis Stevenson's Treasure Island tells the story of young Jim Hawkins, and Dick Shelton, the hero of The Black Arrow, is "not yet eighteen." Stevenson, after being struck from the canon by Virginia Woolf and the Bloomsbury Group, has enjoyed a minor resurgence among academics prompted by Roger Lancelyn Green, one of the Inklings, who also wrote for boys. And, of course, many of those who I mentioned admiring Haggard also admired Stevenson and wrote boys' adventure fiction of their own. I would also be remiss not to mention the Hornblower series by C. S. Forrester, Lost Horizon by James Hilton, and the works of Harold Lamb, Jack London, Daniel Dafoe, Erskin Childers, Anthony Hope, and Rafael Sabatini.

But the boys' adventure novel - that is, stories written to boys "not yet eighteen" and set in exotic, but still broadly historical locales, with perhaps some light fantasy or romantic elements - is something of a dead letter these days. The Young Adult field today is far more focused on the fantasy elements and on stories written to a much broader audience to the degree that the two become easily distinguishable. Perhaps the last culturally relevant example of boys' adventure is Bernard Cornwell's Sharpe series, debuting in 1981. The series sold very well, but it's the exception that proves the rule. If you mention Alan Quartermain today, you'll be lucky if someone remembers Sean Connery's character from the 2003 film The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen. The League opened alongside Pirates of the Caribbean, partly an homage to Stevenson's Treasure Island and itself the last great boys' adventure film. For twenty years that well has been dry as a bone.

Why that is, is not clear. There is of course the politically unsavory frankness with which many of these authors wrote about race and sex. There's the smugly supercilious condemnation of the Bloomsbury Group, an inter-war literary set that succeeded in tarnishing the reputation of Robert Louis Stevenson and having his work pulled from classroom. Of course the Bloomsbury Group didn't hate Stevenson himself so much as they hated the romantic ideals of the Victoria era, and only saw Stevenson as the exemplar of that cultural current. Perhaps their lingering influence can in part account for the decline of the genre. Regardless of how it happened, however, there's no doubt that along with the disappearance of the genre something of great value has been lost. As I have written before, there is a didactic element to fiction. A good story makes moral arguments by showing the result of actions driven by the wants and needs of heroes and villains as they make decisions in the face of challenges and revelations. We, as readers, have the ability to identify with these characters, and thus step into a sort of simulated moral event in which we can experience, in some measure, the results of moral or immoral choices. This simulation helps us learn by example, like an infant trying to copy speech or motions.

Different types of stories offer different strengths arising from what simulated experiences they can provide. A romance plot is of course best suited to teach us about the triumphs and tragedies of love. A bildungsroman is interested in everything attendant to the troubles that go with coming of age. And an adventure story has at its heart a reflection on some of our highest, most vital virtues; those associated with, not only heroism in the face of danger, but the idea that danger must be accepted for the sake of some higher good. Yes, to some degree, the notion that one of narrative's central purposes is to inculcate moral quality is inherently something of a Romantic ideal. If this attitude toward storytelling makes me a 'Romantic', so be it. Haggard and Stevenson, after all, were known for their Romantic style. Of the former, Graham Greene wrote: "Enchantment is just what this writer exercised; he fixed pictures in our minds that thirty years have been unable to wear away."

Plot structure is not the only relevant factor here. If it were, nothing would be lost by leaving boys' adventure behind for modern YA or genre fiction. It's important to remember what boys' adventure means. A true fantasy, that is, something that is focused on the dissimilarity to real life, set in a made-up realm like Mars or Middle Earth, with fantastic magic like space travel or the silmarils, lends itself to a certain type of moral instruction. By placing us in extremis, in a more-than-human setting, these can accelerate the simulated experience far beyond what any of us are likely to experience in life; starker terrors and greater glories. They can also take us outside our own moral frameworks to pose new moral questions that may throw light on those we take for granted.

Yet a somewhat more historical setting like the atavistic wilderness of East Africa or the Spanish Main during the Age of Sail offers a different set of advantages. This niche setting's strength comes as an initiation, particularly germane to the young man, into the moral tradition of real history. Boys' adventure allows the young man to contextualize heroic virtues within specific examples of the historic milieus that gave them life. This is a valuable and foundational process that reinforces the inculcation of morality by connecting it more directly to reality and to cultural heritage. These stories deliver a piece of the latter to the next generation in more concrete terms than the more attenuated flights of fantasy can offer. Another advantage also arises from the closer adherence of the form to realism. Not only is the reader more directly connected to the historical milieu, he more easily identifies with the hero within that milieu.

Of course, there are more fantastic works that cheat this division and make the best of both worlds by means of clever stratagems. In The Lord of the Rings, Tolkien smuggles a historic grounding into his work by a commitment to detailed internal consistency, and by laundering familiar myths from our own distant history for much of his inspiration. Robert Howard's Conan stories, like LOTR, present themselves as having actually taken place in the dimness of our own prehistory. The Picts who troubled the Cimmerians in Howard's tales are, within his conceit, the same Picts who troubled the Romans.

The culture-building purpose of literature is maximized by presenting a range of kinds of stories so that no strength, excellence, or virtue is left unserved. That is the real tragedy of the death of the boys' adventure story. I'm sure you know many people who can recount the history of the War of the Ring or the Infinity War but that would be at a loss if you asked them to recount the history of the War of the Eight Saints, the War of the Grand Alliance, or the War of the Spanish Succession. If someone can explain the Napoleonic Wars, there's a good chance much of their understanding was first formed by reading Horatio Hornblower. Martin's A Song of Ice and Fire, as much as I loathe to admit, succeeds alongside The Lord of the Rings and Conan, if only with respect to the way it smuggles the real history of The War of the Roses into its conceit.

But it was not always necessary to smuggle history. Haggard's She: A History of Adventure sold almost 85 million copies, and has never been out of print since its initial 1887 release. Along with Haggard's other novel King Solomon's Mines - which itself sold over 65 million copies - it is today one of the best-selling books of all time. This genre is criminally underserved today, which ultimately creates a big cultural void. Boys haven't changed as much in the last hundred years as many would have us believe - they still like scurrilous pirates, honorable soldiers, and dashing adventurers. So why isn't anyone in our culture taking advantage of that? My son is going to be in the market for some adventure stories soon; I'd really like for him to know something about his cultural heritage.

Alexander Palacio is a writer of adventurous science fiction and fantasy.

Reader Comments

Decades ago I read to a 5 to 7 year old boy the Harry Potter first volume before he went to sleep. At one point he asked me to continue reading, and I replied, "If you want more, you have to learn to read." He became a prolific reader and hence thinker.