Whether we should defer to 'experts' was a major theme of the pandemic.

Back in July, I wrote about a

study that looked at 'expert' predictions and found them wanting. The authors asked both social scientists and laymen to predict the size and direction of social change in the U.S. over a 6-month period. Overall, the former group did no better than the latter - they were slightly more accurate in some domains, and slightly less accurate in others.

A new

study (which hasn't yet been peer-reviewed) carried out a similar exercise, and reached roughly the same conclusion.

Igor Grossman and colleagues invited social scientists to participate in two forecasting tournaments that would take place between May 2020 and April 2021 - the second six months after the first. Participants entered in teams, and were asked to forecast social change in 12 different domains.

All teams were given several years worth of historical data for each domain, which they could use to hone their forecasts. They were also given feedback at the six month mark (i.e., just prior to the second tournament).

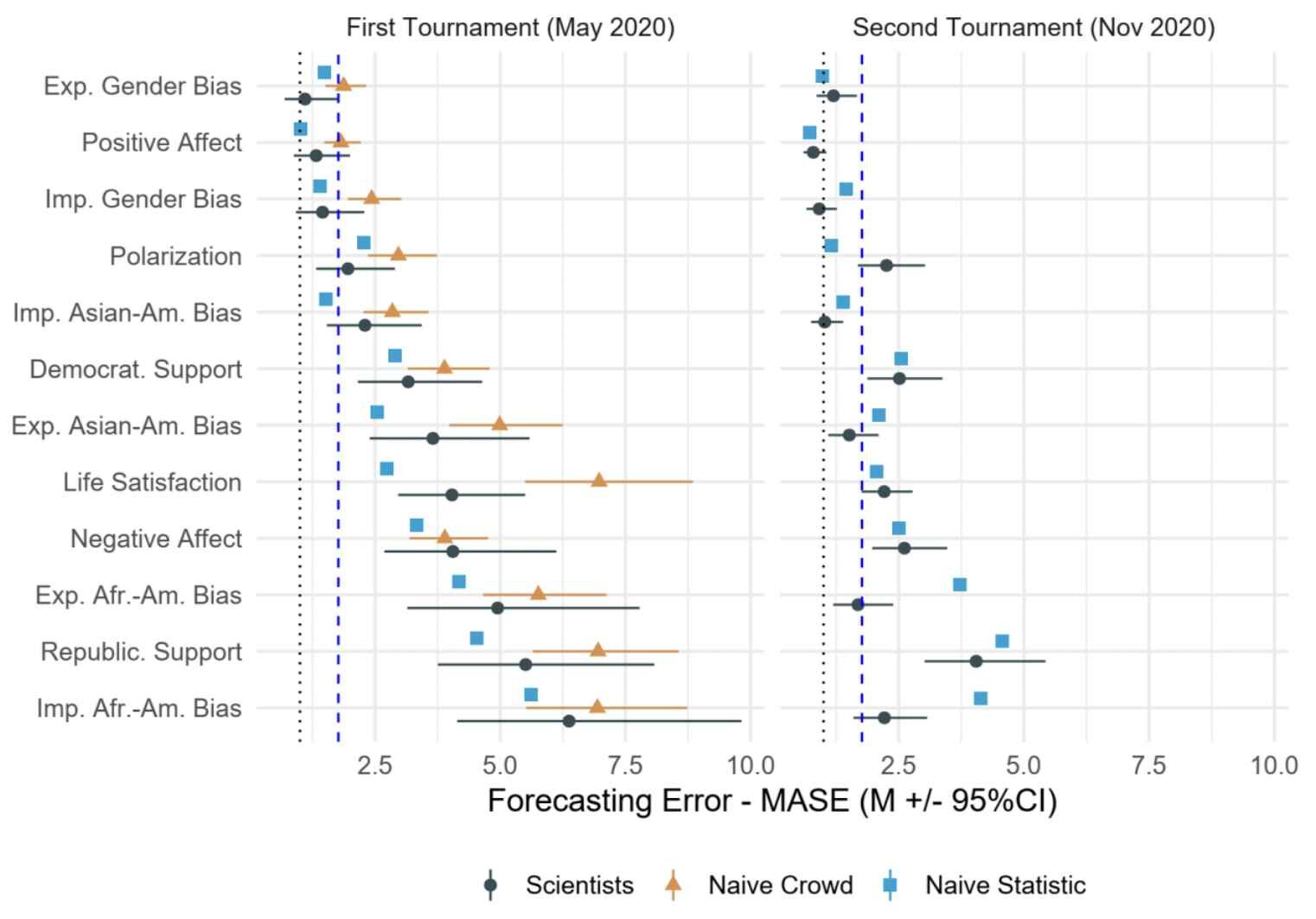

The researchers judged teams' predictions against two alternative benchmarks: the average forecasts from a sample of laymen; and the best-performing of three simple models (a historical average, a linear trend, and a random walk). Recall that another recent study found social scientist can't predict better than simple models.Grossman and colleagues' main result is shown in the chart below. Each coloured symbol shows the average forecasting error for 'experts', laymen and simple models, respectively (the further to the right, greater the error and the less accurate the forecast).

Average forecasting error in 12 different domains for ‘experts’, laymen and simple models.

The researchers proceeded to analyse predictors of forecasting accuracy

among the teams of social scientists.

They found that teams whose forecasts were data-driven did better than those that relied purely on theory. Other predictors of accuracy included: having prior experience of forecasting tournaments, and utilising simple rather than complex models.Why did the 'experts' fare so poorly? Grossman and colleagues give several possible reasons: lack of adequate incentives; social scientists are used to dealing with small effects that manifest under controlled condition; they're used to dealing with individuals and groups, not whole societies; and most social scientists aren't trained in predictive modelling.

Social scientists might be able to offer convincing-sounding explanations for what has happened. But it's increasingly doubtful that they can predict what's going to happen. Want to know where things are headed? Rather than ask a social scientist, you might be better off averaging a load of guesses, or simply extrapolating from the past.

Many equations are empirical - they mostly agree with the physical phenomenon they describe, but the are not axiomatic, and are not the very core of reality itself.

N ot even talking about simulations...

The map is not the landscape.