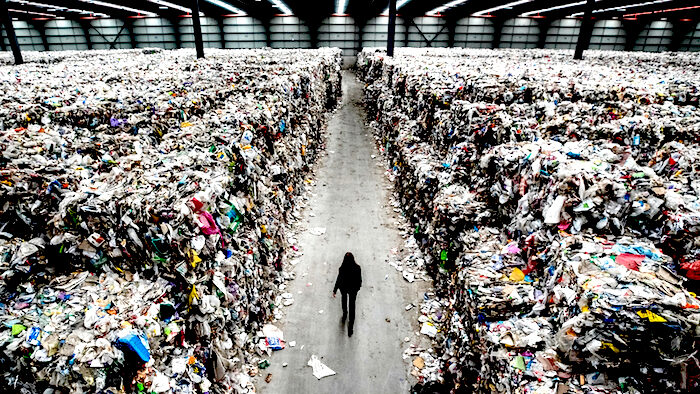

This has been obvious for decades to anyone who crunched the numbers, but the fantasy of recycling plastic proved irresistible to generations of environmentalists and politicians. They preached it to children, mandated it for adults, and bludgeoned municipalities and virtue-signaling corporations into wasting vast sums — probably hundreds of billions of dollars worldwide — on an enterprise that has been harmful to the environment as well as to humanity.

Now Greenpeace has seen the light, or at least a glimmer of rationality. The group has issued a report accompanied by a press release headlined:

"Plastic Recycling Is A Dead-End Street — Year After Year, Plastic Recycling Declines Even as Plastic Waste Increases."The group's overall policy remains delusional — the report proposes a far more harmful alternative to recycling — but it's nonetheless encouraging to see environmentalists put aside their obsessions long enough to contemplate reality.

The Greenpeace report offers a wealth of statistics and an admirably succinct diagnosis:

"Mechanical and chemical recycling of plastic waste has largely failed and will always fail because plastic waste is: (1) extremely difficult to collect, (2) virtually impossible to sort for recycling, (3) environmentally harmful to reprocess, (4) often made of and contaminated by toxic materials, and (5) not economical to recycle."Greenpeace could have added a sixth reason: forcing people to sort and rinse their plastic garbage is a waste of everyone's time. But then, making life more pleasant for humans has never been high on the green agenda.

These fatal flaws have been clear since the start of the recycling movement. When I wrote about it a quarter-century ago, experts were already warning that recycling plastic was hopelessly impractical because it was so complicated and labor-intensive, but municipal officials kept trying in the hope that somebody would eventually find it worthwhile to buy their plastic trash. Instead, they've had to pay dearly to get rid of it, typically by shipping it to Asian countries with cheaper labor and looser environmental rules. In New York City, recycling a ton of plastic costs at least six times more than sending it to a landfill, according to a 2020 Manhattan Institute study, which estimated that the city could save $340 million annually by sending all its trash to landfills.

The environmental price has also been high because the plastic in American recycling bins has gone to developing countries with primitive waste-handling systems. Much of it ends up illegally dumped, burned (spewing toxic fumes), or reprocessed at rudimentary facilities that leak some of the plastics into rivers. Virtually all the consumer plastics polluting the world's oceans comes from "mismanaged waste" in developing countries. There'd be less plastic polluting the seas if Americans tossed their yogurt containers and water bottles into the trash, so that the plastic could be safely buried at the nearest landfill.

The Environmental Protection Agency has promoted recycling as a way to reduce carbon emissions, but its own figures show that the benefits are relatively small and come almost entirely from recycling paper products and metals, not plastic. I've calculated that to offset the greenhouse impact of one passenger's round-trip transatlantic flight, you'd have to recycle 40,000 plastic bottles — and if you used hot water to rinse those bottles, the net effect could be more carbon in the atmosphere.

While finally admitting the futility of plastic recycling, Greenpeace is making no apologies for the long campaign to foist it on the public, and the group is unashamedly pushing a new strategy that's even worse. It proposes finally to "end the age of plastic" by "phasing out single-use plastics" through a "Global Plastics Treaty." This is a preposterous goal — imagine "phasing out" disposable syringes — and would be laughable except that environmentalists have already made some progress toward it. They've found yet another way to harm both the environment and humans, as demonstrated in the movement to ban single-use plastic bags.

Progressive activists may not care that these bans have added to the cost of groceries, inconvenienced shoppers, and caused new headaches for merchants. (After New Jersey forbade stores from offering disposable plastic or paper bags, supermarkets ran out of handheld shopping baskets because so many customers were stealing them.) But progressives also don't seem to care about the implications for climate change and public health.

Banning single-use plastic grocery bags has added carbon to the atmosphere by forcing shoppers to use heavier paper bags and tote bags that require much more energy to manufacture and transport. The paper and cotton bags also take up more space in landfills and produce more greenhouse emissions as they decompose. The tote bags aren't reused nearly often enough to offset their initial carbon footprint, and they're breeding grounds for bacteria and viruses because they're rarely washed properly. Researchers have repeatedly found these bags to be responsible for gastrointestinal infections, but the warnings got little attention until the Covid pandemic suddenly revived respect for disposable products.As stores and coffee shops banned reusable bags and mugs during the pandemic, Americans relearned the lessons of the early twentieth century, when public-health authorities promoted Dixie cups and other disposable products to counter threats like tuberculosis and the Spanish flu. This marked the beginning of the "throwaway society," and the term wasn't originally used pejoratively. Americans welcomed plastic products and packages because they were so much better than the alternative. Cellophane was considered a marvel because it was both moisture-proof and transparent, keeping food fresher and enabling grocery shoppers to see what they were buying. Advertisements featured housewives rejoicing that disposable plates and glasses freed them from dishwashing chores.

Environmentalists' zeal to ban plastic is far more destructive than their former passion to recycle it; it's also harder to explain. Recycling, while impractical, at least offered emotional rewards to hoarders reluctant to put anything in the trash and to the many people who perform garbage-sorting as a ritual of atonement — a sacrament of the green religion. But why demonize plastic? Why ban products that are cheaper, sturdier, lighter, cleaner, healthier, and better for the environment? One reason: the plastic scare helps Greenpeace activists raise money and keep their jobs. Environmentalists need something to replace their failed recycling campaign.

But there's more to it than just financial self-interest. The best explanation I've come up with is that plastic bans are a revival of the sumptuary laws formerly imposed on the lower classes by monarchs, nobles, and clergy. Those laws forbade commoners from owning certain kinds of clothes, jewelry, furnishings, and other products. The restrictions consistently failed to achieve their ostensible purpose of reducing "unnecessary" spending, but sumptuary laws endured until the Enlightenment because they reinforced ruling-class power and status. An English countess could display her superiority by wearing a dress with silver stripes that were illegal for women of lower rank. Spanish prelates and Portuguese monarchs proclaimed their moral virtue and political authority by forbidding the masses from owning clothes, curtains, and tablecloths made of silk.

Today's rulers and moral guardians achieve the same purposes with their petty edicts on plastic. California's law forbidding hotels from offering disposable plastic toiletries is a gratuitous annoyance for travelers who'd like a little bottle of shampoo, but it enables the state's politicians and environmental groups to exercise power and pretend to be saviors of the planet. The pretense is so ridiculous that even Greenpeace will eventually abandon it — but once again, that could take a few decades. The rest of us can start today.

About the Author:

John Tierney is a contributing editor of City Journal and coauthor of The Power of Bad: How the Negativity Effect Rules Us and How We Can Rule It.

Other plastics, lets consider polyester, or PET (polyethylene terephthalate), uses raw materials formed from refined product - the raw materials are ethylene glycol and either dimethyl terephthalate or terephthalic acid and these raw materials if memory serves are formed from xylene with comes from a refinery. Nylon is even more plastic than PET I think - you ever been to a PET plant or a nylon one? I've been to a bunch of em.

Just on the surface it seems cellulose acetate could more easily be recycled versus PET - and recycling PET is energy intensive - hardly worth it.

Really, for most plastics, the best choice when their use is over is to just burn them versus dumping them on land or in ocean.

Any plastic to be recycled needs to be designed for that from the get-go.

I got some ideas on this and I plan on a patent in the not too distant future.

If I make any money out of this, I'll share. I got plenty enough for me and my kin - we don't need much. We are frugal.

Peace is easy,

BK