In February 2011, a British Lieutenant Colonel in Afghanistan, in receipt of daily military Situation Reports from UK special forces, wrote of something he described as "quite incredible". His surprise was regarding the number of Afghan detainees that UK SAS units had sent "back into a building", only for those prisoners to grab a gun or grenade and to then be swiftly killed by their British captors. The Lt Col's superior, the Operations Chief of Staff, replied that such suspicious deaths constituted "a massive failure of leadership". Indeed, they did.

This month it was revealed - in part by Action on Armed Violence (the charity I head up) - that such leadership failed to prevent a killing spree that saw as many as 56 extra-judicial killings by the SAS over a six-month period alone. Hundreds more murders could have occurred. The Chief of Staff wrote:

"If we don't believe this, then no one else will. And when the next WikiLeaks occurs then we will be dragged down with them."Truth, he felt, had a habit of getting out sooner or later. That at least was true.

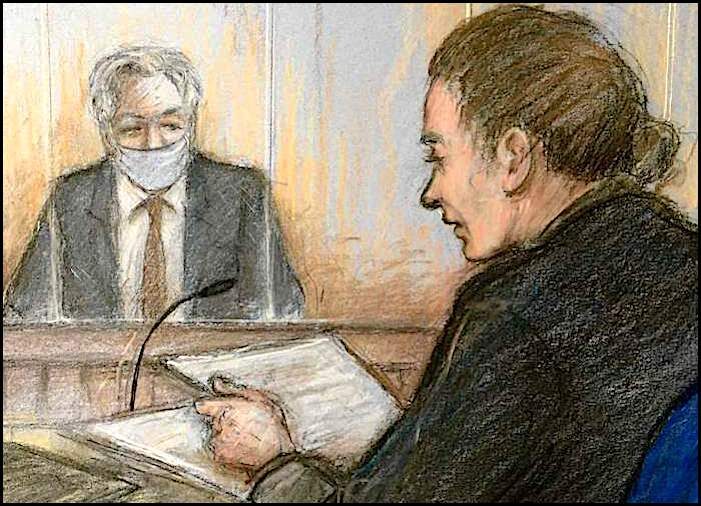

What is not true is that the exposé of UK Special Forces would come from WikiLeaks. In part, this might be because Julian Assange today lies in a British jail, his extradition to your country approved by the UK Home Secretary Priti Patel. It seems that a very effective way to stop someone exposing British or American death squads is to lock them up.

This, of course, creates an awkward situation - one in which the perpetrators of war crimes go unprosecuted by the British or American state, but those who pose a threat to such perpetrators (through exposing their murderous atrocities) can find themselves facing prison sentences of up to 175 years. Because, as far as I can see, Assange's only crime has been the publication of confidential - but damning - military documents.

As someone both involved in the investigation into UK Special Forces killings and in WikiLeaks' expose of human rights abuses by military forces in Iraq (as former head of the Bureau of Investigative Journalism - my team won an Amnesty Award for its reporting on those leaked reports), I am very concerned about this imbalance.

I do not know, for instance, where you - as US Ambassador - draw the line between protecting your national interests and eviscerating public interest journalism.

Could I, for instance, also be extradited to the United States because I helped expose instances of American troops opening fire on surrendering Iraqis? Could I be forced to stand trial in Washington for handling those same documents that Julian Assange handled when together we exposed torture in American and Iraqi-run jails? And can you assure me that I do not risk spending years of my life in solitary confinement - like Julian - for exposing US-run extraordinary rendition operations?

I write this, in part, out of deep sympathy for Julian. But I also write because I don't know the answers.

Terror has a habit of coming in different forms. For some, it is a masked Special Forces operative breaking down your door on a Helmand dawn and murdering your unarmed son. For some, it is waking to a Belmarsh breakfast, unable to hug your children or wife, because in another life you revealed the true face of war. And for others it comes in the lack of knowing if - by just doing your best as a journalist to expose atrocities and holding power to account - you might forfeit the very liberty you fight so hard to protect.

Where, Ambassador, do you stand on this terror? For it or against?

Please let me know.

but those who pose a threat to such perpetrators (through exposing their murderous atrocities) can find themselves facing prison sentences of up to 175 years. Because, as far as I can see, Assange's only crime has been the publication of confidential - but damning - military documents.

maybe our Russian and Chinese friends can send in a few hyper strikes at the rainbow house and parliament..

the US now have killed the same bloke twice now, 20 november 2020, as reported in "the sun", and yesterday, amazing truth by the nazi sponsors'

who would think the leader of the free world is a freakin pedo with a crackhead meth dealing child shacking nutjob son that laundered money in nazi state ukraine

what a wonderful world we live in!!

democracy died decades ago..