The claim is said to come from a new study from Imperial College which analysed immune system responses (note: not actual reinfection rates) in vaccinated healthcare workers with varying infection histories. Note that all the participants were triple-vaccinated, so no comparison is made with the unvaccinated.

Professor Danny Altmann, from Imperial's Department of Immunology, was downbeat in his assessment of the findings.

The message is a little bleak. Omicron and its variants are great at breakthrough, but bad at inducing immunity, thus we get reinfections ad nauseam, and a badly depleted workforce. Not only can it break through vaccine defences, it looks to leave very few of the hallmarks we'd expect on the immune system - it's more stealthy than previous variants and flies under the radar, so the immune system is unable to remember it.According to the Telegraph report, Omicron infection does "virtually nothing against Omicron itself". They found that in people who were triple vaccinated and had no prior infection, an Omicron infection provided an immune boost against previous variants such as Alpha, Beta, Gamma, Delta and the original ancestral strain, but virtually nothing against Omicron itself.

People infected during the first wave of the pandemic and then again with Omicron also lacked any immune boosting, an effect the researchers have termed "hybrid immune damping".

Is it true that the researchers found that an Omicron infection provided "virtually nothing" in the way of protection against Omicron re-infection? No, it is not. In fact, they found the opposite.

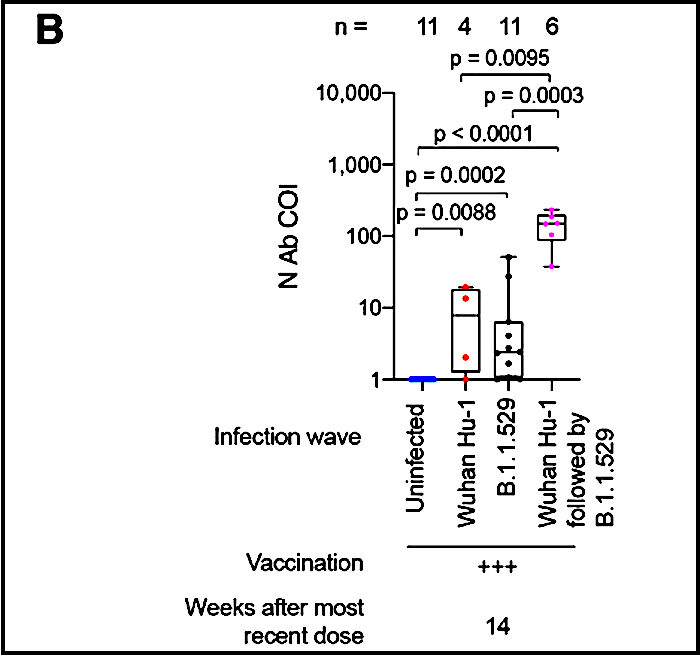

First of all, it's worth saying they found that vaccination by itself (so with no infections) produced negligible immune responses against Omicron. The triple-vaccinated but never-infected, they write, "made no nAb IC50 response against B.1.1.529 (Omicron) 14 weeks after the third vaccine dose", which indicates "rapid waning" of neutralising antibodies to zero. "nAb IC50" means the concentration of neutralising antibodies necessary to reduce viral infectivity by 50%, and is a measure of antibody potency against a virus. They state that three doses of the vaccines provide "poor protection against transmission".

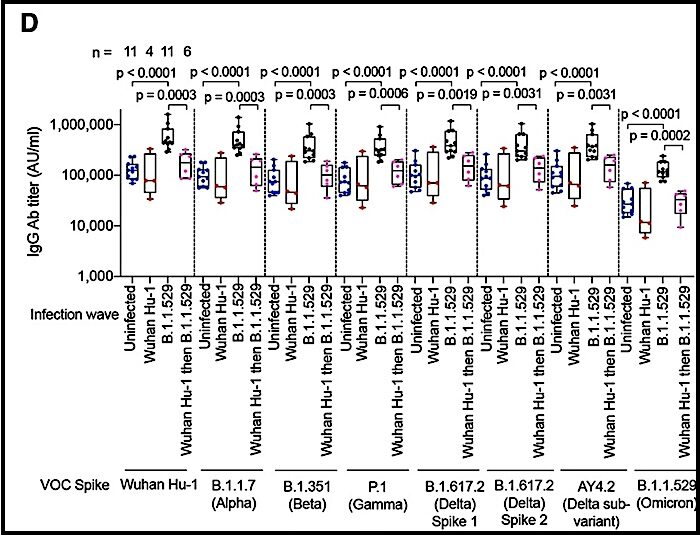

As to the immune response induced by an Omicron infection, below is a chart showing their findings for N-type antibody binding against SARS-CoV-2, 14 weeks after a third vaccine dose.

Each dot represents the antibody level for one healthcare worker's blood sample. The important thing to spot is that the black dots, which represent healthcare workers who were vaccinated and then infected for the first time with Omicron (B.1.1.529), are largely higher than the blue line, which is the baseline antibody level of someone who is uninfected (though, like all participants, triple-vaccinated). Clearly there is a boost in antibodies here, albeit highly varied (three points are very low). It is not much different to the antibody boost of those who were infected in the first wave (and then vaccinated), i.e., the red dots.

Notably, those who were infected in both the first wave and the Omicron wave (and vaccinated), shown in pink, have very high antibody levels - N.B. it is a logarithmic scale and the pink dots are over a hundred times higher than the blue line (set at 1.0), whereas the red and black dots are mostly under 10 times higher than the blue line. This suggests that two infections give much stronger protection than one infection (at least in the vaccinated), and may indicate that herd immunity will improve significantly following second infections.

Note that N-antibodies are the antibodies that target the virus nucleocapsid (body), which is common to all variants, rather than the spike, which varies between variants. Thus on this point alone it is incorrect to say that Omicron infection does "virtually nothing against Omicron itself". It provides a boost of N-antibodies, particularly when it is a second infection (at least following a Wuhan-strain infection, if not other variants). The authors themselves acknowledge this:

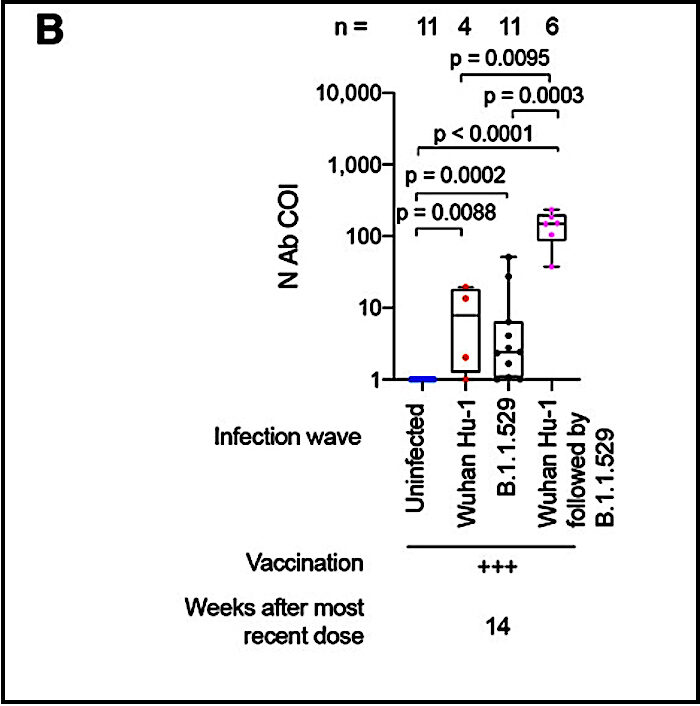

"Infection during the B.1.1.529 (Omicron) wave produced potent cross-reactive antibody immunity against all [variants of concern], but less so against B.1.1.529 (Omicron) itself." Less so, but certainly not nothing. Thus it is false to say, as per the Telegraph, that "people infected during the first wave of the pandemic and then again with Omicron also lacked any immune boosting".Against the spike protein, too, an Omicron infection provides an antibody boost. In the chart below, focus on the column on the far right, which shows the different IgG antibody levels against the Omicron spike protein for healthcare workers with different infection histories (the other columns show the IgG antibody levels against the spike protein of different variants).

The important thing to spot is that in the far-right column the black dots are considerably higher than the blue dots. The black dots represent healthcare workers who were infected for the first time in the Omicron wave (after being triple-vaccinated), and this shows they have considerably higher antibody levels against the Omicron spike protein than the blue dots, which represent never-infected (though vaccinated) healthcare workers. Thus again we see an antibody boost against Omicron from an Omicron infection, not "virtually nothing".

Note that this time the pink dots are not higher than the blue dots. The pink dots, recall, are those who were infected during the first wave, then vaccinated, then infected again during the Omicron wave. We saw above that they had an N-type antibody level a hundred times higher than a never-infected person, and much higher even than someone infected once (whether with the Wuhan strain or Omicron). Yet here they have a lower level of S-type antibodies against the Omicron spike protein. The authors explain that this is an example of "immune imprinting" (a.k.a. Original Antigenic Sin, OAS), whereby the original Wuhan infection inhibited the immune system's ability to produce antibodies specific to the Omicron spike protein. Since immune imprinting is known to occur with the vaccines as well, it would be interesting to compare the antibody level of an unvaccinated (and not previously infected) person following Omicron infection.

Crucially, though, the very high N-type antibody levels suggest that the impairment from the immune imprinting of the Wuhan S-protein is amply compensated for elsewhere. This is a long way from "virtually nothing" against Omicron re-infection. Omicron provides natural immunity too. We are not doomed to keep on catching it forever.

Note that all of this concerns infection and re-infection. It doesn't say anything about protection from serious disease and death, which is likely to be much more robust.

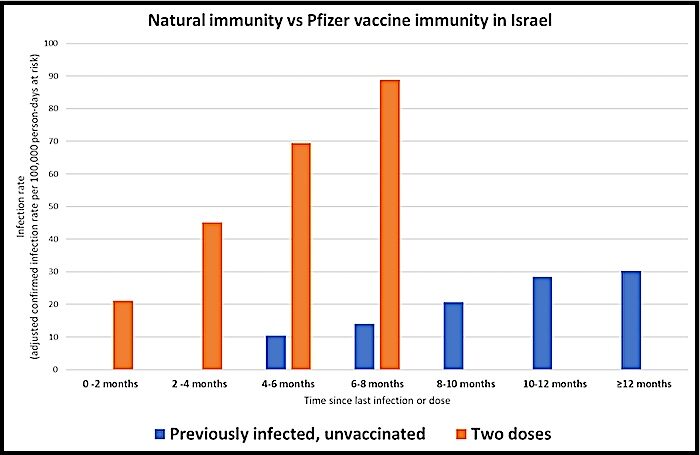

As a postscript, a neat study appeared recently in the NEJM which compared vaccine immunity to natural immunity in Israel (so with the Pfizer vaccine). The difference is stark, with natural immunity being far stronger and lasting far longer (note this is based on Delta infections, not Omicron). The chart below illustrates the massive difference between the double-dosed (and not previously infected) in orange and the previously infected (and not vaccinated) in blue.

The bars show the infection rate by time since last dose or infection. Notice how the orange bars increase in height quickly, reflecting fast-waning vaccine immunity. By contrast, at 4-6 months and 6-8 months the blue previously-infected bars are much lower, and even at 12 months-plus the bar is below even where the vaccinated were at 2-4 months, and the decline appears to have plateaued. Our immune systems still seem to be working.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter