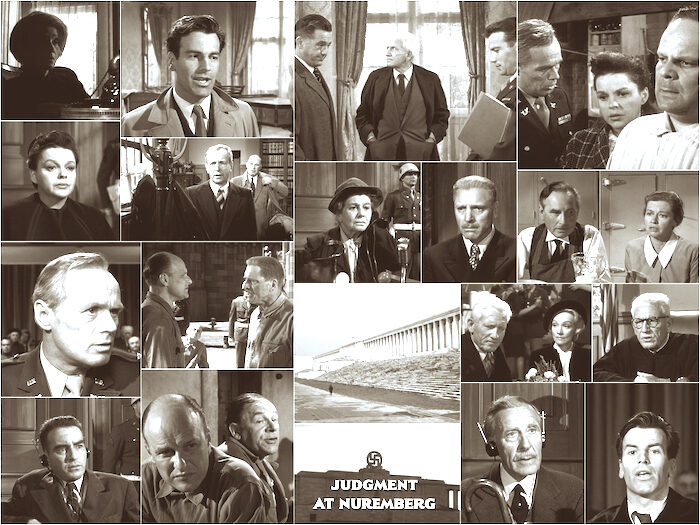

© screenshotsStanley Kramer film classic from 1961: "Judgement at Nuremberg"

I recently had the occasion to re-watch, after oh so many long decades, the Stanley Kramer classic from 1961,

Judgment at Nuremberg. And the viewing experience resonated into

an unavoidable series of comparisons with the current state of the world. Of course, there are so many people who, while during the era of the Trump presidency couldn't stop themselves endlessly condemning as fascists and Nazis, Trump, his supporters and indeed anyone who wasn't prepared to offer similar unqualified denunciations,

but today bristle at the alleged absurdity and unreasonableness of using those same historical precedents when reflecting upon the current COVID hysteria. And yet,

as the Kramer film illustrates, the comparisons are difficult to ignore.The usual resort to invoking the Nuremberg trials among critics of the COVID regime is to

cite the legal precedents established that it was a violation of international law for the government to compel medical procedures upon its citizens. Indeed, Kramer's film explicitly

addressed the questions of forced sterilization. It even had the even-handedness to acknowledge that the

real-life Nazi's got their ideas of sterilization from practices in the so-called democracies, including the United States and Canada. Some see the vaccine passport programs now being introduced all over the world as violating that Nuremberg precedent.

Nay-sayers will dismiss this comparison in objecting that no one is being compelled or coerced into receiving the vaccine. Maybe no one is being held down and injected, but

when the alternative is official second-class citizenship - in which failure to comply prevents one from legally traveling, attending a wide range of public events and locations, including going to school, and for many entails being terminated from their employment (even in some cases where they have no social contact with others in performing their job) -

this "lack of coercion" objection rings hollow.

The government's legal designation of second-class citizens, and the requirement of all citizens to produce papers upon demand, demonstrating their good standing in the eyes of the government, of course draw even more uncomfortable comparisons with the era of the film. Likewise, hearing police officers defend the enforcement of such government dictates with the claim that they are just doing their job echoes bitterly with the most notorious association to the Nuremberg trials: i.e., leading Nazi officials, who were eventually sentenced to death,

defended their actions as being that of loyal soldiers just following orders.Kramer's film though does not merely rehearse these themes, already well established by the 1960s. Judgment at Nuremberg has a more specific and focused point to make, and it is in this regard that the resonance with the current situation is perhaps most disturbing. The film takes place late in the series of trials. The main Nazi ringleaders, at the time of the film, have already been tried and sentenced. There's a controversy among the Germans over

whether these mid-level officials should be tried and treated the same way as those who molded and dictated Nazi policies. In the specific case of the film, it is four German judges who are on trial.

It is judges, and indeed, in a sense, judgment itself, which is to be judged in this trial, and film. The defendants are accused of

having corrupted the law in the interest of advancing the policy of the government. Such a prospect is especially galling. For surely the judiciary, in a free society, is the citizen's last peaceful line of legal defense against the over-reach and abuse of the government.

In this light, the

abdication by courts around the world of their duty to defend their citizens against brazen and draconian government measures, suppressing fundamental rights, casts a grim shadow over the judiciary. Fortunately, in the United States, courts have begun to enforce the constitutionally protected religious and health exemptions from vaccine mandates. Elsewhere, though, the picture remains all too bleak.

In Canada, for instance, notwithstanding the country's flowery promising Charter of Rights and Freedoms,

the courts have consistently deferred to the extra-parliamentary rule of the Prime Minister's Office and the anointed public health czars. At the point of writing, to my knowledge,

no judge has required any government to present in court any evidence — scientific, medical, public health, economic or otherwise — to justify their draconian measures and suspension of constitutional and parliamentary norms. Such judicial acquiescence is of course defended in the name of the common good.

The nation faces a great crisis, bold and dire actions are required. This though is precisely what needs to be proven, not merely obediently assumed.

The courts are the forums in which such evidence needs to be heard by the public. In their failure to stand up to the government, the judges have failed the Canadian people. This is not a speculation, but an observation of history. That failure is already a fact for the textbooks.

And it is precisely in this regard that Kramer's film is most poignant. As the prior post to this Substack emphasized,

the erratic and irrational pandemic mitigation policies have been contributing to just the kind of swelling social chaos that

lays the ground for the triumph of pathocracy. Now, where I will concede some ground to those mentioned above (notwithstanding their hypocrisy regarding the Trump era), who object to this comparison, it is true that our own social chaos would have to degenerate a long way down the road of pathocracy to get to the place of the crimes evoked in

Judgment at Nuremberg. Though, to those who'd make that argument with the claim that the comparison is absurd, as the Nazis are the worst criminals known to humanity, I'd ask:

have you ever studied the crimes of Mao or Pol Pot? If not, you might be surprised that there are even greater, more brutal and dehumanizing evils that can be visited upon humans than even the efficient Germans conjured. Yes,

even evil is measurable in degrees along a spectrum.

Starting at the modest end of that spectrum can all too easily lead one toward the other end.That, as it happens, in its final moments, is the message left to us by Stanley Kramer's film. Thematically the film revolves around two characters - though one gets much more screen time than the other. Burt Lancaster plays a German judge, who unlike the other three judges on trial, was never a true believer, and put at risk a prestigious career as a jurist. As the story unfolds,

it becomes clear that he made this compromise with his principles for two reasons. First, he had hoped that rather than simply retiring from the bench, as others did, if he stayed involved, there was the chance that he might be able to have a positive, moderating influence on the direction of jurisprudence under the Third Reich.

[i] But, secondly,

while he recognized that he was compromising his principles, he believed that his country was under attack, and defending that country, in its moment of great crisis, necessitated compromising one's personal ideals. The common good, in this moment of crisis, required standing by the government, which was trying to save the people.

The movie pulls few punches in allowing expression to the other side of the arguments. We are treated to repeated expressions of fear that Germany was under serious assault by communism - both domestic and foreign. And that the blockading of Berlin is taking place precisely as the events in the film unfold, frequently discussed by characters, emphasizes that this was not a trivial or baseless fear in Germany of the late 20s and early 30s. Still, the main protagonist, the lead American judge in the trial, played by Spencer Tracy, struggle though he might in his efforts to understand

what constitutes justice under these remarkable conditions, concludes in his dramatic judgment that

those who subvert the law in the perpetuation of evil, for whatever self-justified cause, even in the name of the common good, must share in the guilt of those who precipitated the conditions of evil.By the end of the film, despite the chasm that separates them in life experience and their different places within the trial process, clearly Lancaster and Tracy's characters have grown to respect each other. As Tracy's character is packing to return home, he receives word that Lancaster's character wants to speak with him.

This meeting is the denouement of the film; its final few minutes. Their meeting begins with brief acknowledgements of their mutual respect, at least within the limits of their roles within the trial. Then, in a final plea for understanding,

Lancaster's character says to him, you have to understand, all those people who were killed; I never knew it would come to that. To which Tracy's character explains: it came to that the first time that he corrupted the law to serve the policies of the government.I know no better than anyone else where the current drift toward pathocracy is taking us. Is this just a brief blip of public hysteria,

or have we started down that dark path, that so many in history before have passed, to their horror and misery. What I do know is that -

whatever is coming, regardless of whatever one thinks about the legitimacy of the pandemic panic -

we have already been betrayed by all those judges who deluded themselves into believing that some greater common good was being achieved by corrupting the law in service of the policies of the state. Their job was to defend us. In the moment of truth, they failed. Let us hope that their failure is not a harbinger of us descending into the world into which such failure has tragically led so many before us.

[i] For those interested in, and knowledgeable about, such things, it struck me as possible that Burt Lancaster's character was meant as a stand in for Carl Schmitt. Lancaster's character is described as a world renown legal scholar who'd written some of the most important books on the law and jurisprudence, which is not an unreasonable description of Schmitt at that time. Schmitt of course never did go on trial but was subject to intense and extensive interrogation by Allied investigators, some of whom did want to see him tried. The claim that he joined the party in the hope of moderating its extremism was part of his defense to his interrogators. I couldn't help wondering if someone - writer, director, producer - involved in this film helped mold it as a statement on what they think should have happened to Schmitt.

In Australia the Rule of Law has long since been destroyed. Here is an article I did on a case some years ago where that point is well illustrated - [Link]