So far this year, officials have confirmed 90 cases of acute flaccid myelitis, a condition in which the gray matter of the spinal cord becomes damaged, leading to muscle weakness and paralysis in one or multiple limbs. It is called AFM for short.

Still, the CDC does not yet know what is causing the spike in cases. Scientists are exploring a range of possible explanations, including whether the condition may be caused by an aberrant immune response to an infection, not the infection itself, Dr. Nancy Messonnier, director of agency's National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases, told reporters.

Scientists are also considering whether the cause of the illness isn't being detected because a pathogen is hiding somewhere in the body, or because the cause of the condition had already cleared the body when limb weakness developed, she said.

"We're not sure if the reason we're not finding pathogens in all of these patients is because it's cleared [from their systems]. Is it because it's hiding? Is it because it's something we haven't tested for?" Messonnier said.

Even in patients in whom a pathogen was found, it's not clear that it was the cause of the illness, she said. "What we do know is that these patients had fever and respiratory symptoms three to 10 days before their limb weakness. And we know that it's the season where lots of people have fever and respiratory symptoms. What we need to sort out is what is the trigger for the AFM."

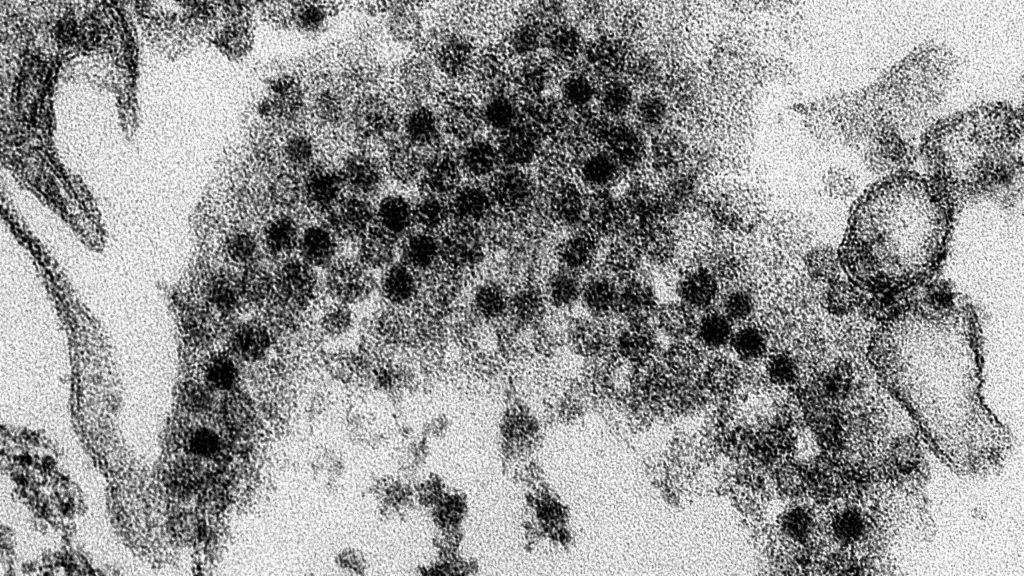

A burst in cases of acute flaccid myelitis was first reported in the United States in the fall of 2014; 120 cases were eventually confirmed. That phenomenon coincided with a large outbreak of enterovirus D68 (known as EV-D68), leading health officials to suspect it was the likely culprit.

Few cases - 22 - were reported in the fall of 2015. In 2016, cases again surged, with 149 children confirmed as having the condition. But in 2016 there was no EV-D68 outbreak recorded, Messonnier noted.

The increase in cases appears to follow a pattern, with a year of a high number of cases followed by a year with few. This year is following the pattern.

A number of the patients - who are mostly children under 4 years of age - recover. But quite a few appear to have long-term problems, said Messonnier, who acknowledged the CDC doesn't have follow-up information on all of the cases at present. So far this year none of the cases recorded in 2018 has died, she said.

Messonnier spoke to reporters about a new report on acute flaccid myelitis that the CDC rushed to print in its online journal Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Review. The report, by CDC scientists, shows how complicated this search is.

The report is an analysis of 106 patients, mostly children, who suffered rapid onset of limb weakness. Of that group, 80 were confirmed to have acute flaccid myelitis, six others were deemed "probable" cases, and the remaining 20 were ruled out as cases.

The CDC tested 125 stool, respiratory tract, and cerebral spinal fluid (CSF) specimens from 71 of the confirmed patients. Only two had enteroviruses in their CSF; one had enterovirus D68 and the other A71.

Just over half of stool and respiratory tract samples from this group of patients showed evidence of enterovirus or respiratory viruses. All the stool samples were negative for polioviruses.

Finding a pathogen in spinal fluid would be considered strong evidence it was the cause of the condition because normally there should be no bacteria or viruses in spinal fluid, Messonnier said. In contrast, taking a swab of the respiratory tract or checking a stool sample could pick up a number of viruses that are present but are not causing the illness.

The report revealed that the 20 children who were deemed not to be cases of acute flaccid myelitis also had evidence of infection with a range of the same viruses, including enteroviruses D68 and A71, a number of rhinoviruses (the main cause of the common cold), and various echoviruses. Most of those positive samples were stool and respiratory tract specimens, but one child had an echovirus in his or her spinal fluid.

Could this be similar to polio and its return even tho vaccinated?