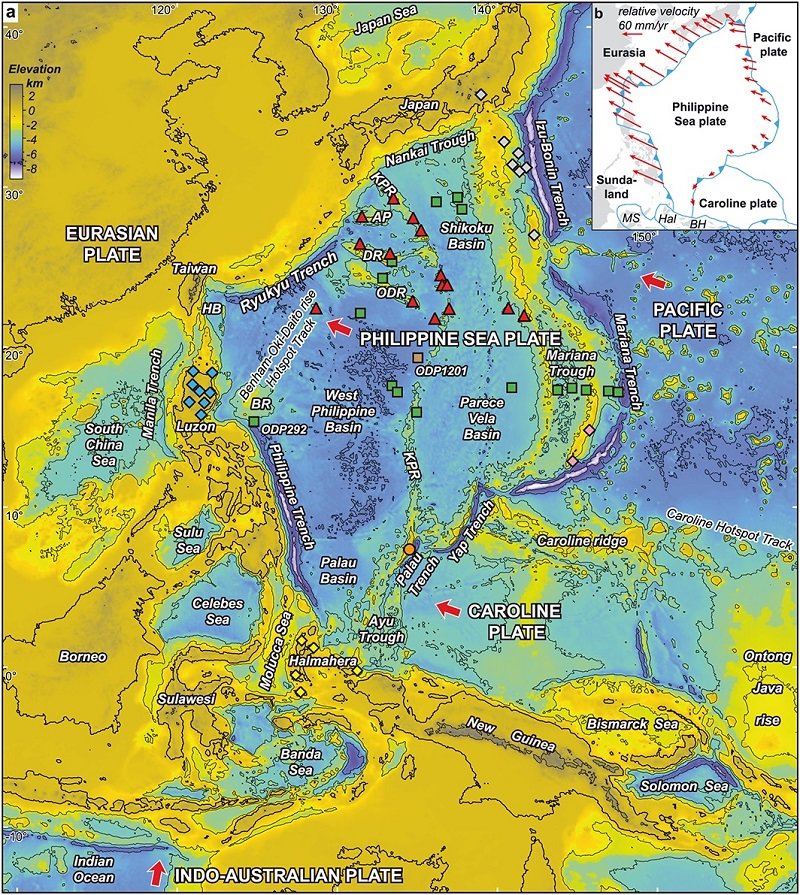

© Journal of Geophysical ResearchPresent-day Philippine Sea and East Asian tectonic setting.

Using images constructed from earthquake data, geoscientists have developed a method for resurrecting a "slab graveyard" of tectonic plate segments buried deep within the Earth,

unfolding the deformed rock into what it may have looked like up to 52 million years ago. This helped the researchers identify the previously unknown East Asian Sea Plate, where an ancient sea once existed in the region shortly after dinosaurs went extinct.

The Philippine Sea lies at the juncture of several major

tectonic plates. The Pacific, Indo-Australian and Eurasian plates frame several smaller plates, including the Philippine Sea Plate, which researchers say has been migrating northwest since its formation roughly 55 million years ago.

In the process, the Philippine Sea Plate collided with the northern edge of the East Asian Sea Plate, driving it

into the Earth's mantle. The southern area of the East Asian Sea Plate was eventually subducted by, or forced beneath, other neighboring plates, the researchers said.

Geologists attempting to reconstruct the past were once limited to visible evidence of slow-moving changes, such as mountains, volcanoes or the echoes of ancient waterways. But with new imaging technologies, scientists can now glean information from hundreds of miles within the Earth's interior to map distant history.

The slabs were previously identified with an imaging technique called

seismic tomography, which uses earthquake waves and multiple monitoring stations to determine the speed at which different waves travel through the Earth. Those waves generally travel more quickly through old chunks of tectonic plates that "sink through the mantle, like a leaf through water," said study lead author Jonny Wu, a geologist formerly at National Taiwan University and now at the University of Houston.

Wu and his colleagues at National Taiwan University focused on an area around the Philippine Sea, in part because of good data from the many seismic monitoring stations in this

earthquake-heavy region.

"East Asia has been a place where plates have been coming together, converging and disappearing from the Earth's surface in a process called subduction," Wu told Live Science. "Because the information you're looking for to piece together the history of the area is actually disappearing from the Earth's surface, it's made it very difficult."

The East Asian Sea Plate was pieced together by a process of elimination when all but three of the 28 subducted slabs in the model had been traced back to connections with other modern plates.

The region is also home to many relatively small tectonic plates, known as microplates, where movement is hard to reconstruct. "Those plates have long been tectonic mysteries, because it's really difficult to work out where they've been in the past," Wu said. "Just like if it's a puzzle, small fragments can fit in all these ways."

The findings could provide researchers with a clearer picture of the history of the

Philippine Sea and its surrounding regions.

"The work [is] a groundbreaking advance in our understanding of the deep Earth structure in the most complex parts of the Eastern Hemisphere," Sabin Zahirovic, a geologist at the University of Sydney who was not involved in the study, told Live Science in an email.

The new study is also a step toward a much-needed technical method of interpreting models built from earthquake data, said Hans-Peter Bunge, Chair of Geophysics at Ludwig Maximilians University in Munich, who was not involved with the new research.

"Normally we would not have full access to the complexity of the interior structure," Bunge told Live Science. But this "important" new technique fills in the information missing from the seismic tomography images with carefully constrained guesses at what the material might be, and how the plates have moved, he added.

And the researchers aren't stopping there. "As we keep working in other areas with a lot of unknowns — for example, South America or the Himalayas — we'll continue to test these methods and refine them, and hopefully contribute new ideas to Earth science," Wu said.

The research was published online June 25 in the

Journal of Geophysical Research: Solid Earth.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter