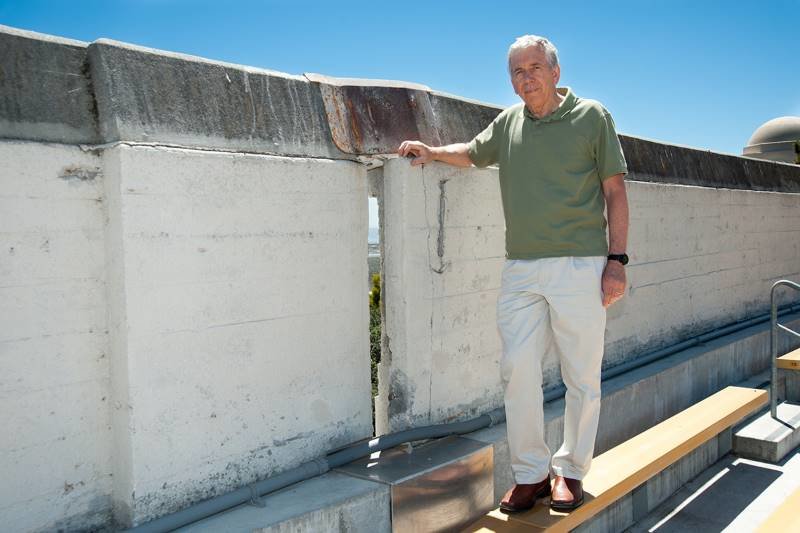

Nicholas Sitar is a professor of civil engineering at UC Berkeley, and he likes to joke that "earthquakes don't come with due dates." Yet he and other scientists say it's only a matter of time — maybe days, more likely a few years — before a major Earth-shaking catastrophe hits the East Bay.

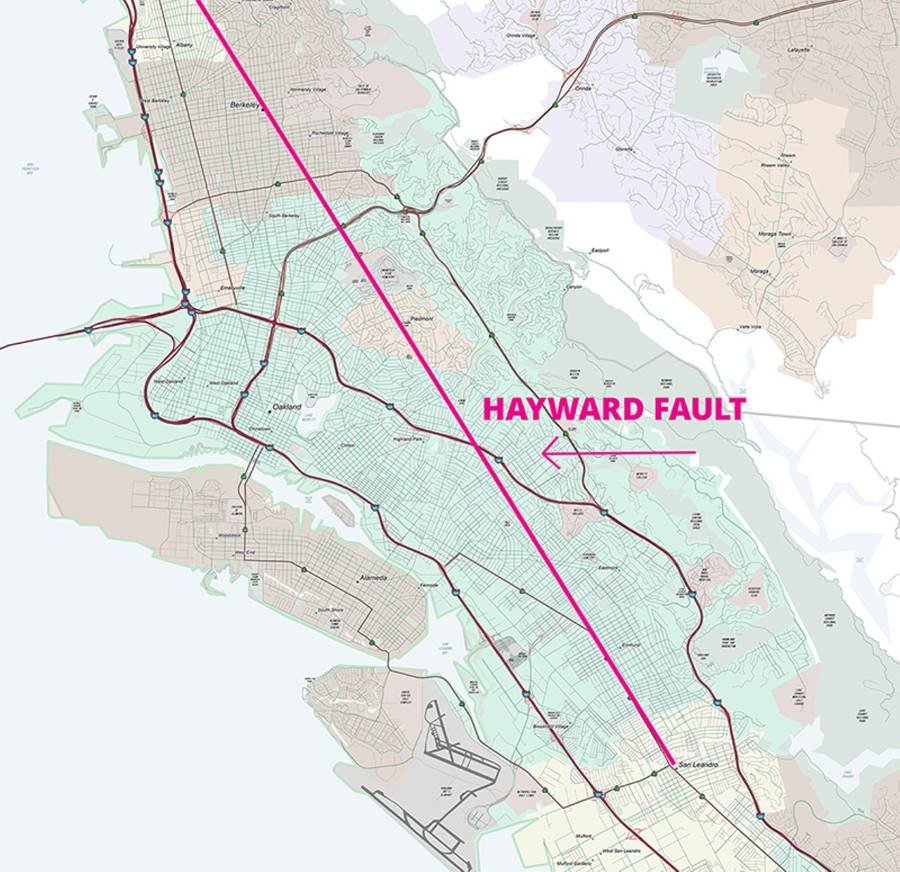

Their words are not scare tactics. The Hayward Fault runs nearly right through the heart of the region, splitting the flatlands from the hills. This 74-mile-long zone has been quiet since 1868, when it generated its last large earthquake. But scientists explained to the Express that the average time frame in which a large tremblor occurs on the Hayward Fault is about 140 years. And that period lapsed in 2008. "Yes, in terms of the statistical average, we are now well past the average period between earthquakes," is how Sitar put it.

This means that, in layman's terms, the proverbial Big One is overdue.

The professor is among many scientists who spend their time considering what would happen if a quake similar in size to, or perhaps substantially more powerful than, the 1868 Hayward Fault shaker struck Oakland and the greater region today. Nearly all agree that it would be a terrible disaster.

The shaking of a 7.0 magnitude earthquake would cause tremendous and unprecedented destruction. Thousands of buildings — even dozens of hospitals that are rated by state officials as seismically unstable — could be destroyed. Gas and water lines would break, and fires would leave the region reeling, if not wholly crippled, for days. Looters and thieves almost certainly will take advantage of abandoned homes and busy police and emergency officials.

Even less-dramatic experts such as Sitar concede that hundreds of people will die. Others expect a death toll in the thousands.

The silver lining is that agencies in the East Bay are at least somewhat prepared. Bay Area Rapid Transit has largely quake-proofed the more significant pieces of its system, such as several parking buildings, the Transbay Tube, and many miles of aerial tracks. PG&E and the East Bay Municipal Utility District likewise say they have been working to seismically fortify their systems, especially the major transmission pipes.

The other sort-of-good news is that the Hayward Fault has its limits. The biggest quake it can generate is probably something on the order of a magnitude 7.5 — smaller than the devastating 9.0 quake off the coast of Japan in 2011, but still pretty damn big.

But what makes the Hayward Fault really scary, though, is its location: It runs smack through densely populated urban areas, clusters of inadequately reinforced buildings, and tangles of freeway overpasses (see a map on page sixteen). And just because these structures survived the 1989 earthquake does not mean they are quake-proof — by a long shot.

Stanford University professor of geophysics Mary Lou Zoback, who has analyzed Bay Area earthquake hazards for years, warns it would be a grave error to assume that the '89 trembling was a sound assessment of the region's infrastructural integrity. She says that, when the Big One hits, thousands of buildings will fail their first true seismic stability test. Many will entirely collapse, crushing scores of office workers. Or, if at night, sleeping residents.

Ken Hudnut, a scientist with the United States Geological Survey, says the Hayward Fault is probably going to generate an earthquake like no one alive has experienced.

"A repeat of the 1868 earthquake will be way, way, way worse than the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake," he said. "There will be many people killed."

How Big and How Bad?

Just about everyone who lived in the Bay Area in '89 remembers what happened on October 17. At 5:04 p.m., just as game three of the World Series between the A's and the Giants was beginning, the Earth shook so hard that the Nimitz Freeway collapsed in Oakland, killing 42 people. A section of the Bay Bridge fell, and a devastating fire erupted in San Francisco's Marina District. It seemed at the time like the Big One had struck. The next morning, the San Francisco Chronicle ran a headline claiming the earthquake had left "hundreds dead." It was a terrifying figure — and fortunately an overestimate. Sixty-three people died in that quake.

In fact, the Loma Prieta shaker on the San Andreas Fault was not very large. It rang in at a medium-big 6.9 on the Richter scale — about the same as the Hayward Fault's 1868 quake, which killed thirty people.

Since the Richter scale is not linear but logarithmic, the 1906 quake's 7.8 magnitude was eight-times larger and 22-times more powerful than the Loma Prieta upheaval, according to a calculation formula used by the United States Geological Survey.

Moreover, neither the 1906 tremblor nor the Loma Prieta quake actually struck an urban area. The earlier one's epicenter was in northwest Marin County, and the '89 earthquake shook hardest in the Santa Cruz Mountains.

An East Bay epicenter could be a whole lot worse.

In a report from 2008, seismologists calculated that a repeat of the 1868 Hayward Fault quake — which was centered in that city — would cause monumental damage.

More than 100,000 people would be left homeless. And the damage toll - from the shaking only and not from possible post-quake fires - would run roughly $165 billion. That report came from the Risk Management Solutions, an East Bay consulting firm, and the Hayward Earthquake Alliance.

Stanford professor Zoback used to work for Risk Management Solutions and co-authored the 2008 study. She says a big lurch of the Hayward Fault would likely kill hundreds, and possibly thousands, of people. "But probably not tens of thousands," she said.

A 2010 report from San Francisco's Community Action Plan for Seismic Safety Project estimated that a 7.2 earthquake on the San Andreas fault would make 27,000 buildings in San Francisco — about one in five — unsafe to dwell in. Nearly 4,000 buildings would need to be demolished, too. The report also estimated the earthquake would start more than seventy fires, which could destroy another 2,000 to 3,000 buildings. Total damages from the earthquake and fire might run $34 billion. Three-hundred people could die. The report warned that a repeat of the 1906 quake could kill nearly 1,000 people.

The injury and death toll would have much to do with the hour that the earthquake strikes, Zoback says. The worst time of day to experience a large earthquake in the Bay Area would be mid-afternoon, when many people are at work. "Having lots of people in buildings is the concern, since, if just one of them collapsed, you could have lots of people killed," she said.

The potentially disastrous consequences of a mid-sized earthquake striking a city in a developed nation were seen on Tuesday, January 17, 1995, in southern Japan. At 5:46 in the morning, a magnitude 6.9 earthquake caused several feet of lateral and vertical displacement of two adjoining tectonic plates. The city of Kobe was left in ruins, and more than 6,000 people died.

Though the Loma Prieta quake gave millions of people an idea of what a big earthquake feels like — and also revealed weak points in social infrastructure and building codes, and helped officials map out developed areas of artificial fill prone to disastrous shaking — it wasn't a serious field test of the Bay Area's seismic tolerance, according to Rundle.

"So it's a very big problem," he said. "An earthquake [on the Hayward Fault] is going to be much stronger and very different than what we saw in Loma Prieta."

Read the rest here.

All these "what will happen if...." articles about predictions/ prophesies of big disasters to California are getting pretty boring.