© www.theguardian.com"Deliverology" Children in the next generation.

On Friday November 6, Toyota announced that it's investing $1 billion in the

Toyota Research Institute, a new company dedicated to R&D in artificial intelligence and robotics. Based in Silicon Valley, the Institute will be headed by noted roboticist Gill Pratt, who has been tasked by the Japanese automotive giant with developing the next generation of autonomous cars. Starting in January 2016, he and his colleagues will also be dedicated toward the goal of applying, "Toyota technology used for outdoor mobility to indoor environments, particularly for the support of seniors."

Even if it's still too early to predict the fruits of this new enterprise, the investment of a billion dollars is considerable testimony to Toyota's belief that coming decades will increasingly feature robots as a part of our daily experience. Neither is it the only major corporation staking its future in artificial intelligence; Apple, Google, Facebook, Intel, Yahoo, LinkedIn and Twitter all contributed to the $2 billion invested in AI in

2014.

Many of these companies have fairly prosaic, industry-focused aims for their robot activities, with Google

acquiring AI-startup Deepmind in Jan 2014 as part of its ongoing quest to enhance its search engine, and with Intel purchasing Saffron AI last month in a bid to enable its chips to perform "

cognitive computing."

Yet many of these companies harbor more grandiose, utopian ambitions when it comes to their forays into the brave new world of robots and artificial intelligence.

Beginning with Toyota, the corporation wants its research into robotics to bear dividends with "

cars that don't crash." As it declared in its announcement of TRI, it wants to build service robot; that is,

robots that enter the home and assist people with everyday chores.Similarly, Facebook's much vaunted virtual assistant, M, is devoted to "

capturing all of your intent for the things you want to do," and thereby offering uncannily tailored suggestions for your web browsing and consumption. No less significant, Google has been making inroads into your home by gobbling up companies involved in the

Internet of things (IoT), while simultaneously investing in AI firms that manufacture

humanoid robots and

smartwatches.

Things are still at an immature stage; nonetheless, all of this activity heralds an endeavor on the part of Toyota et al.

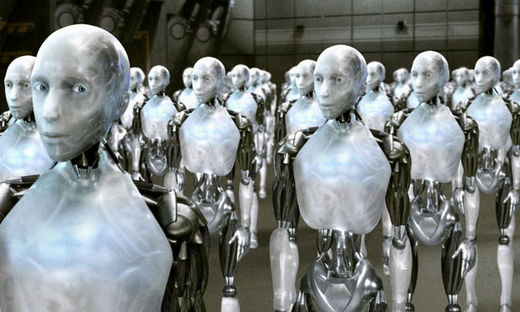

to make artificial intelligence an ubiquitous element of daily life. The Japanese corporation, as well numerous others worldwide, has begun a process which appears intent on implanting a robot servant in as many households as possible. Whether in anthropomorphic form, or in the shape of cars and television sets,

these AI-infused machines will involve themselves in even the most mundane of activities, from reading a bedtime story to lowering a thermostat.As salutary as this might prove for the aged, infirm or pathologically busy, the pervasiveness of such technology may bring certain unsavory risks. These risks don't reside with the so-called "

singularity"—a hypothetical state of affairs in which humanity will be outstripped in all departments by its new robot masters.

The risk relate to how the introduction of robotics into every area of human activity will result in a corresponding formalization and robotization of humanity itself.With artificial intelligence suggesting to people what to consume, when to turn the heating down, when to get out of bed, and when to do anything else,

people will find themselves becoming ever more regularized and automated in their behavior. Regardless of the fact that AI is characterized by its ability to adapt, to learn from how its putative user reacts, it can adapt only so far (especially in its present form) and can perform only so many actions. This means that

any person who allows AI into their home will have to adapt to its behavior; will have to begin conforming to their robot helper's way of doing things, to its rhythms, schedules and choices. As such, they will become more formalized and systematized, losing much of their spontaneity, impulsiveness and autonomy in the process.A less dramatic, already realized example of this process is available in the guise of the

automatic recommendations Amazon provides its customers. These are produced by a simple algorithm that "intelligently" works on the basis of what the client has purchased in the past, what he or she has viewed, and what other clients with similar purchase histories have viewed and bought. If you've engaged in any shopping on the website recently, you'll know that these are

often inaccurate. On the basis of buying only one DVD, perhaps as a gift for someone or out of sheer curiosity, you're inundated and followed around by recommendations for movies you don't really dig.

Imagine such off-the-mark typecasting on the level of a domestic robot or smart gadget. It acquires an initial, cursory feel for the kind of person you are, purely after sensing a few of your acts, and then it proceeds to behave toward you as if this classification were a reliable indicator of the future. It won't occur to the robot that there might have been any number of contingent, haphazard reasons as to why you wanted a bedtime story on Thursday night or wore an angry expression on Monday morning. It doesn't know you as well as your friends or your family, yet it operates as if it did, repeatedly plying you with the same activities and suggestions.

Because of this increased tendency toward repetition and inflexibility, the AI or robot assistant will make its "master" more repetitive and inflexible. Its master will come to divide her time and spend her day according to algorithms which, no matter how advanced, are still nowhere near as complex as the human brain. Therefore,

with growing frequency, she may be reduced to a mere function of these algorithms, pressured into acting in accordance with her android butler, into adopting the stereotype it foists on her.Because these AIs would be the product of single R&D centers, such as the Toyota Research Institute, this

influence of robots on human behavior will also represent a general homogenizing and centralizing of said behavior. Instead of being the result of innumerable interactions with hundreds of people and with her own community, the AI user's psychology and personality will be molded to a greater extent by Toyota, Google or Facebook, particularly if this user becomes more socially isolated and more reliant on robotic aids.

This scenario is still a very long way off, and it's tenable that our home appliances already force a certain kind of robotic regularity on us anyway. Nevertheless, if such corporations as Toyota do bring us to the stage where personal robots and AI are a daily fixture in our routines, we will have to tread carefully, since this encroachment would amount to our robotization.

In order to coordinate ourselves with the robots in our homes and receive their "help," we would have to start acting more like them, basing our daily habits and our own selves on what they're programmed to do, or on what they're programmed to advise us. This would entail a loss of the inspiration, creativity and sovereignty that arguably makes us human, and in its wake we would become less able to lead our lives according to what we believe is best for ourselves.

That's why we should be a little wary of any announcement like Toyota's, and why we should think twice before opening our doors to robots.

Not because they might one day become more intelligent than us; but because we might one day become as stupid as them.

Alternet is a sick joke. It always was. It is an apparatchik media apparel for fooled and stupified moronic readers and listeners and viewers who think or wish themselves chic or something. Think Alfred E. Neuman, not realizing he is Alfred E. Neuman. Can the lazy man and coward achieve enlightment?

Truth is not so easy and definitely not so chic. It is tough, difficult.

I think that Sott, has a slight potential for actual truth, based on its non interference with commenters and comments despite their antics (free speech, DUH) and its slightly more diversified reporting with somewhat less pathogenic editing. It is a very fine line though. One that would happily be given over to razor wire and tear gas and other 'crowd control' measures, in an instant, for everyone's safety of course.

Please commenters and readers and even the 'editors' of Sott, realize what a dangerous position your 'immortal' soul is in. 'Immortality' lasts only for a limited time when you cheat, lie and swindle so many others for a better position in the widespread MAMMON SCHEME. You are killing yourself when you do this, in other words.

Gollum is really not that cool, though he offers you shape shifting (and other marvelous) wonders, if you follow. And you do, follow.

Alternet is a joke.

ned, out