The Southern Education Foundation reports that 51 percent of students in pre-kindergarten through 12th grade were eligible under the federal program for free and reduced-price lunches in the 2012-2013 school year. The lunch program is a rough proxy for poverty, but the explosion in the number of needy children in the nation's public classrooms is a recent phenomenon that has been gaining attention among educators, public officials and researchers.

"We've all known this was the trend, that we would get to a majority, but it's here sooner rather than later," said Michael A. Rebell, the executive director of the Campaign for Educational Equity at Columbia University, noting that the poverty rate has been increasing even as the economy has improved. "A lot of people at the top are doing much better, but the people at the bottom are not doing better at all. Those are the people who have the most children and send their children to public school."

Comment: Yes, the rich are getting richer and poor are getting poorer. It has been that way for a long time in the United States. It's a system that rewards the greedy, psychopathic individuals and those with a conscience get left behind. One wonders why so many other countries wish to emulate the U.S.

The shift to a majority-poor student population means that in public schools, more than half of the children start kindergarten already trailing their more privileged peers and rarely, if ever, catch up. They are less likely to have support at home to succeed, are less frequently exposed to enriching activities outside of school, and are more likely to drop out and never attend college.

It also means that education policy, funding decisions and classroom instruction must adapt to the swelling ranks of needy children arriving at the schoolhouse door each morning.

Schools, already under intense pressure to deliver better test results and meet more rigorous standards, face the doubly difficult task of trying to raise the achievement of poor children so that they approach the same level as their more affluent peers.

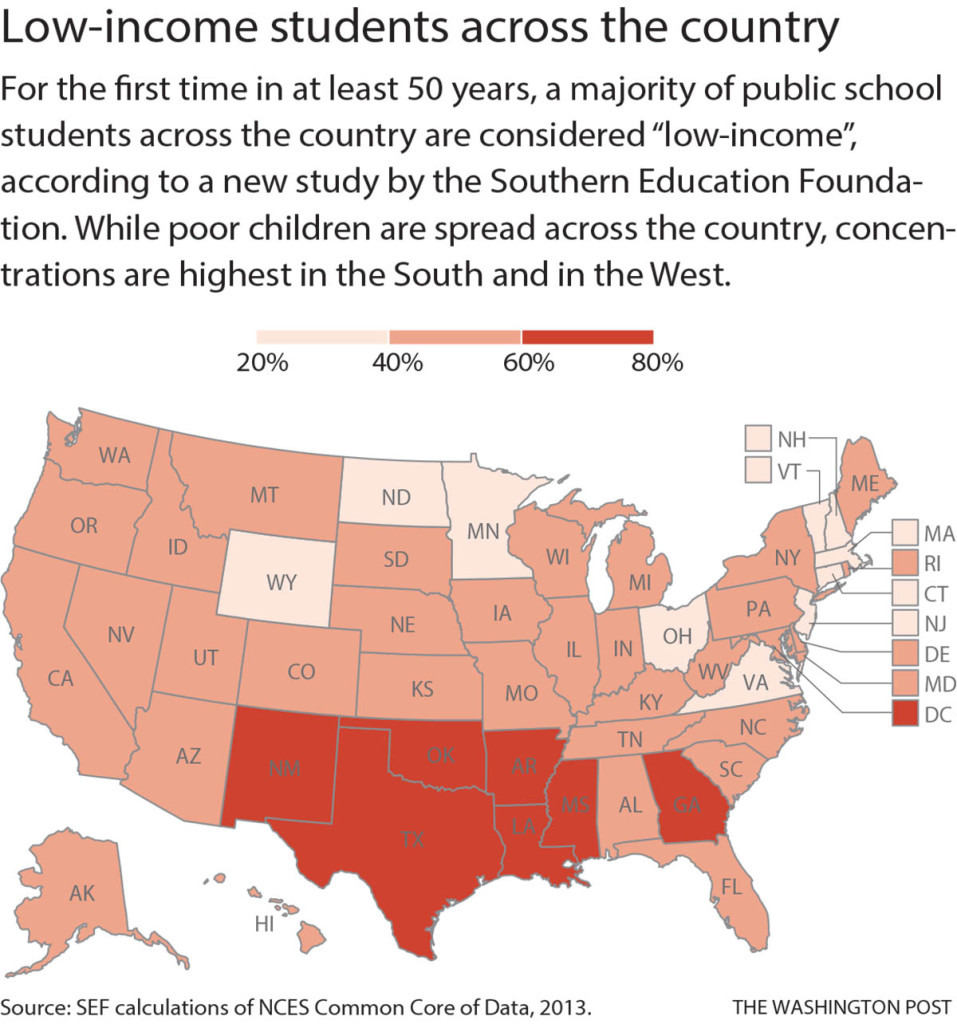

"This is a watershed moment when you look at that map," said Kent McGuire, president of the Southern Education Foundation, the nation's oldest education philanthropy, referring to a large swath of the country filled with high-poverty schools.

"The fact is, we've had growing inequality in the country for many years," he said. "It didn't happen overnight, but it's steadily been happening. Government used to be a source of leadership and innovation around issues of economic prosperity and upward mobility. Now we're a country disinclined to invest in our young people."

The data show poor students spread across the country, but the highest rates are concentrated in Southern and Western states. In 21 states, at least half the public school children were eligible for free and reduced-price lunches - ranging from Mississippi, where almost three out of every four students were from low-income families, to Illinois, where one out of every two was low-income.

Carey Wright, Mississippi's state superintendent of education, said quality preschool is the key to help poor children.

"That's huge," she said. "These children can learn at the highest levels, but you have to provide for them. You can't assume they have books at home, or they visit the library or go on vacations. You have to think about what you're doing across the state and ensuring they're getting what other children get."

Darren Walker, president of the Ford Foundation, was born in a charity hospital in 1959 to a single mother. Federal programs helped shrink the obstacles he faced, first by providing him with Head Start, the early-childhood education program, and later, Pell grants to help pay tuition at the University of Texas, he said.

The country needs to make that same commitment today to help poor children, he said.

"Even at 8 or 9 years old, I knew that America wanted me to succeed," he said. "What we know is that the mobility escalator has simply stopped for some Americans. I was able to ride that mobility escalator in part because there were so many people, and parts of our society, cheering me on.

"I don't think today that low-income children and their families feel that America is cheering them on. We need to fix the escalator. We fix it by recommitting ourselves to the idea of public education. We have the capacity. The question is, do we have the will?"

The new report raises questions among educators and officials about whether states and the federal government are devoting enough money - and whether it is allocated in the most effective way - to meet the complex needs of children living in poverty.

The Obama administration wants Congress to add $1 billion to the $14.4 billion it spends annually to help states educate poor children. It also wants Congress to fund preschool for those from low-income families. Collectively, the states and the federal government spend about $500 billion annually on primary and secondary schools, with about $79 billion coming from Washington.

The amount spent on each student can vary wildly from state to state. Vermont, with a relatively low student-poverty rate of 36 percent, spent the most of any state in 2012-2013, at $19,752 per pupil. In the same school year, Arizona, with a 51 percent student-poverty rate, spent the least in the nation at $6,949 per student, according to data compiled by the National Education Association. States with high student-poverty rates tend to spend less per student: Of the 27 states with the highest percentages of student poverty, all but five spent less than the national average.

"The problems are as big as they've ever been over the last 50 years, and yet the relative level of public investment to face those challenges is really modest," McGuire said.

Republicans in Congress have been wary of new spending programs, arguing that more money is not necessarily the answer, and they have rebuffed President Obama's calls to fund preschool for low-income families. A number of Republican and Democratic governors have initiated state programs in the past several years.

The report comes as Congress begins debate about rewriting the country's main federal education law, which was first passed as a part of President Lyndon B. Johnson's "War on Poverty" and was designed to give federal help to states to help educate poor children. The most recent version of the law, known as No Child Left Behind, has emphasized accountability and outcomes, measuring whether schools met benchmarks and sanctioning them when they fell short.

That federal focus on results, as opposed to need, is wrongheaded, Rebell said.

"We have to think about how to give these kids a meaningful education," he said. "We have to give them quality teachers, small class sizes, up-to-date equipment. But in addition, if we're serious, we have to do things that overcome the damages of poverty. We have to meet their health needs, their mental health needs, after-school programs, summer programs, parent engagement, early-childhood services. These are the so-called wraparound services. Some people think of them as add-ons. They're not. They're imperative."

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter