When late Tory MP Geoffrey Dickens tried to expose public figures he claimed were involved in a Westminster child sex ring in the 1980s, Thomas, who was in the Speaker's chair at the time, had himself been blackmailed over his homosexuality.

Furthermore, The Mail on Sunday has been told of claims that Thomas, who later became Viscount Tonypandy, propositioned young men in the Speaker's official grace and favour apartment in Parliament.

A senior political source said: 'Thomas had an interest in young men and did not hide it at Westminster.'

In the 1960s, Thomas was a Minister in the Home Office, which is accused of losing over 114 files on alleged child sex cases, including Dickens's dossier in the 1980s.

And he reportedly used his Home Office position to help Liberal leader Jeremy Thorpe - who was later acquitted of attempted murder of his gay lover - to cover up an alleged homosexual offence against a minor.

The disclosures follow the announcement of official inquiries into claims of a Westminster paedophile ring and a Home Office cover-up.

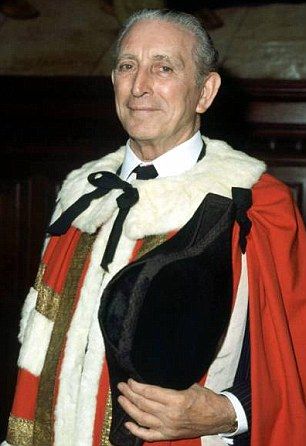

Thomas, who died in 1997, was one of Britain's best-loved and most influential public figures as Speaker from 1976 to 1983.

Comment: How likely is it that the only perverts who will be exposed in this scandal are the ones who are already dead?

A Methodist lay preacher, he was a Home Office Minister in Harold Wilson's Labour Government and joined the Cabinet.

As Speaker, he had unrivalled power, including control of Commons debates, security and disciplining MPs and even reading the lesson at Prince Charles's 1981 wedding to Lady Diana Spencer.

Close friend and fellow Welsh Labour MP Leo Abse revealed before his death in 2008 that his friend and ally Thomas lived in constant fear of being unmasked as a homosexual.

Abse, who led the campaign to legalise homosexuality, said Thomas was blackmailed for being gay and added: 'The slightest tremor of scandal, however faintly reverberating into his private domain, reduced him to jelly.

'In 1976, I found him grey-faced and trembling,' said Abse.

'Investigative journalists were pursuing inquiries into Thorpe. They had reached the conclusion that 16 years earlier, political intervention saved Thorpe from being prosecuted for a homosexual offence against a minor.

'They believed that when Thorpe became embroiled in another scandal in 1964, he feared Home Office records of his earlier misbehaviour would wreck his efforts to free himself.'

Abse said Thorpe - using his friend, fraudster and Liberal MP Peter Bessell, as an intermediary - 'turned to George for help. Yielding to Bessell's importuning, George set up a private meeting between Bessell and the Home Secretary [Frank Soskice]'.

'George was frightened the journalists would be more interested in his own sexual proclivities than in Thorpe's,' added Abse.

'He asked for £800 to pay extortioner... he felt trapped'

By LEO ABSE

Labour MP Leo Abse, who led the campaign to legalise homosexuality, died six years ago. In 2001, in a book on Tony Blair, Mr Abse revealed how his friend, the former Commons Speaker George Thomas, was secretly blackmailed for being gay.

The phone rang at 6am. 'George here,' came a familiar voice. It was my friend George Thomas, secret homosexual and - until barely a year beforehand - superb Speaker of the House of Commons.

His voice sounded strangulated, and George was sobbing.

'I'm in terrible, terrible trouble. Come quickly.'

I immediately thought he was phoning me from a police station. My heart sank. I feared he was about to be crushed by scandal.

I knew I had to dash to him; he would panic if there was the slightest sign of a crack in the thin ice upon which he skated all his life.

George was 75 and one of the best-known men in Britain.

He had been Speaker for seven years, an MP since 1945, Home Office Minister in the 1960s and Secretary of State for Wales. He was a prominent lay preacher, read the lesson at the wedding of the Prince and Princess of Wales, and enjoyed a warm relationship with the Queen Mother.

During his political life, George could benignly sublimate his inclinations.

But those inclinations could not always be contained under the fraternal rubric. Sometimes, overwhelmed, what he regarded as lapses did occur.

Given his exposed position, it was inevitable that he would fall victim to blackmail. On one occasion, after a distraught recounting to me of the pressure upon him, I insisted I would meet and deal with the young criminal in his Cardiff constituency into whose hands he had fallen.

The blackmailing cur had no doubt that, unless he desisted, I would carry out my threat to ensure he was put behind bars for ten years. Shortly after our encounter, he found it politic to quit the city.

George had always been on the edge of catastrophe.

I learnt he was visiting a grubby cinema in Westminster where, under cover of the darkness, groping prevailed unchecked. I warned him against his lack of discretion.

Alarmed that I had been able to know about his haunt, he thereafter kept well away from it.

But there were times when my advice had gone unheeded. While still a backbench MP, he asked me for a loan. The specificity and size of the loan, £800, aroused my suspicions.

He poured out the story. I urged him to let me deal with this extortioner. But to no avail. That sum - the ticket and resettlement money which was to take the man to Australia - would, George insisted, mark the end of the affair.

I had profound misgivings but I could see George was near breaking point. I gave him the money.

The slightest tremor of scandal, however faintly reverberating into his private domain, reduced him to jelly.

One such occasion was in 1976 when, summoned to his sitting room in the Speaker's house, I found him grey-faced and trembling. Journalists were pursuing inquiries into the then Liberal leader, Jeremy Thorpe.

They had concluded that, 16 years earlier, political intervention saved Thorpe from being prosecuted for a homosexual offence against a minor.

They also believed that when Thorpe became embroiled in another scandal in 1964, he feared Home Office records of his earlier misbehaviour would wreck his efforts to free himself.

Thorpe - using fraudulent Liberal MP Peter Bessell, as an intermediary - had turned to George, then a junior Home Office Minister, for help.

Yielding to Bessell's importuning, George had set up a private meeting between Bessell and the Home Secretary.

The journalists wanted a probing interview with George. He felt trapped.

He was frightened his motivation in assisting Bessell was under scrutiny and that the journalists, if denied the interview, would become more interested in his own sexual proclivities than in Thorpe's.

I had noted at funerals and marriages his penchant for using texts from the epistle to the Corinthians (on the 'sin' of homosexuality) - as he would again in the marriage of the Prince and Princess of Wales in 1981.

I told him he must pull rank and indicate the impropriety of the Speaker granting a private interview. He took my advice, and regained his equanimity.

He never again turned to me for assistance - until that poignant early-morning call in 1984, the year after his retirement.

It turned out he was not at a police station, as I feared, but in a hospital. Puzzled and concerned, I rushed to him.

There was, I knew, a link between his past flights into illness and dangerous threats of exposure.

Once, when he was a backbencher, it drove him into hospital with a bout of shingles. Sometimes, overwhelmed with praise, his guilt at the encomiums being bestowed upon such a 'sinner' crushed him. (He collapsed at a party given for him at Guildhall to celebrate his 80th birthday.)

I wondered, as I approached the hospital that dawn, what ghost had visited the haunted man this time. Before I even arrived, he phoned my wife three times.

I reached George's bed and found him convulsively sobbing. He grabbed my hand and said he was ruined. Soon the whole world would know that he was in hospital suffering from ... venereal disease.

I chastened him to get a grip. 'Waterworks' was the answer, I explained. He should allow it to be known he had been rushed to hospital with prostate difficulties.

It worked. George entered enthusiastically into the tale I had created for him. He even sent me, from the hospital, a beflowered 'thank you' card obviously designed to be shown to my wife.

It read: 'Dear Leo, I shall be for ever grateful. Strangely enough there had been no need for me to worry - it was all in my brain! I am due for the prostate gland operation next Wednesday. Love to you all. George.'

My wife laughed indulgently at his naivety that she would be deceived; but it helped George to think so and very soon he was out of hospital - taking, I hoped, the precautions that would avoid his ever again being placed in such a predicament.

Once, after I had saved him from the consequences of some escapade, he could not contain his anger against the homophobic hostilities which had so dogged him.

With tears in his eyes, he railed: 'Bust them, Leo. I do not care a damn what is said after I'm dead but I couldn't stand them taunting me in my lifetime.'

Extract from Leo Abse's book Tony Blair: The Man Behind The Smile, Robson Books, 2001.

what does it takes to be an MP in GB?... does one have to have a sexual attraction for minors of their gender, or is it just to be a peter puffing, scrotum groping ass monkey, with their sights set on anyone (young boys) who can be coerced to please them?... what a bunch of sick, power-abusing psychos, as well are the police, the adolescent watchdog agencies, the churches and the orphanages!!... and as the comment noted- I also hope that all who will be exposed have not already died