Yet already the law, coming on top of previous legislation, is speeding the demise of an American small-business institution; the one-doctor medical practice.

Their problems began in the late 1990s. Government cost controls steadily eroded revenues while simultaneously boosting costs, by stacking on requirements for paperwork and accounting.

Some doctors adapted by figuring out ways to see more patients. Others just accepted falling incomes.

Now federal health care policy has delivered a major blow to productivity.

In a slow-motion version of the problems that crippled online insurance "exchanges" for months, doctors who see patients under Medicare and Medi-Cal programs have been forced by the phase-in of a 2009 federal "stimulus" law to install expensive, complex software systems that sharply reduce time for patients.

For many doctors, it's the final straw. Surveys suggest that older physicians are retiring in high numbers. Younger ones are closing practices and taking jobs with integrated health systems.

Early this month, I spent a few hours with my friends Dr. Doug Moir, a heart specialist in Escondido, and his wife, Margaret, who runs the business side of their one-doc practice (which also includes a nurse and assistant).

Both Moirs are pillars of the Escondido community. Just thinking about their volunteer schedule wears me out.

"This year we're looking at putting money into the business to keep it going," he said.

Federal data backs up Margaret's account of revenue pressure.

Pricing is largely set in the U.S. by Medicare, the federal program for people over 65 (most of Doug's patients), which pays on a fee schedule that covers thousands of procedures and provides a benchmark for private insurers.

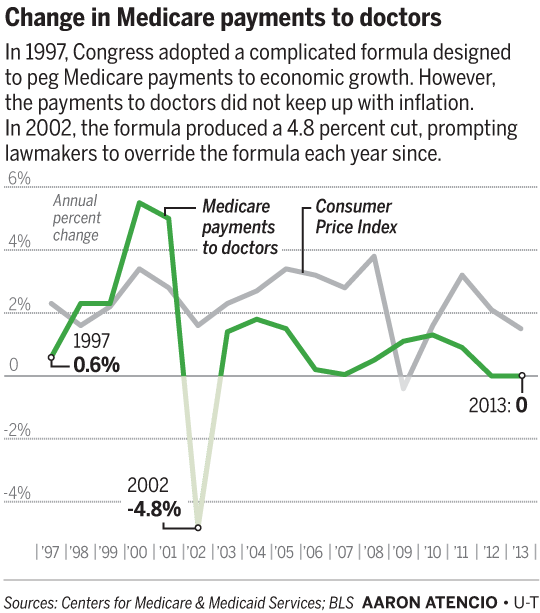

In 1997, Congress imposed a payment formula that, at first, kept pace with costs. But in 2002, the formula produced a 4.8 percent reduction, prompting lawmakers to intervene each year.

Since then, increases have ranged from zero to 1.8 percent, far below inflation.

Doug Moir is a noninvasive cardiologist, which means he doesn't perform lucrative procedures like heart surgery or inserting stents. As a specialist, he can't easily crank up patient throughput by handing off procedures to less-skilled assistants.

Payment problems

According to Medicare's database, Doug's average payment in 2012 was $52.70 for a Doppler echocardiogram, which uses sound waves to peer inside a working heart. In 2011, the national average was $86.64.

Under a quirk in the Medicare formula that is eventually being fixed, payments are lower in San Diego County, which the government viewed as a low-cost, rural county.

Both figures strike me as modest; medical references say an echocardiogram can take from 20 minutes to one hour to complete.

My plumber often gets a better hourly rate. And my plumber usually gets paid.

Margaret Moir has a file full of outrages. One bill went out in 2009 for $450 to Medi-Cal, the state-federal program for the poor that generally pays less than Medicare. Last month - four years later - a check arrived for $61.72.

Doug is rated highly by patients, so he qualifies for federal quality bonuses; one check came for 9 cents, another was for $2.14.

Nearly every doctor has similar examples of ridiculous payment practices. Yet the unkindest cut has been the electronic records mandate.

Nearly 70 percent of physicians say digitizing patient records has not been worth the cost, according to a survey by Medical Economics magazine. This negative cost-benefit view comes even after $27 billion in subsidies to health care providers for the systems.

One big problem is the dozens of systems don't talk to each other, because the feds didn't mandate interoperability before the rollout.

So communication gains among hospitals, clinics and doctors offices aren't happening. Adding insult, doctors can be criminally liable if hackers get hold of patient data.

Dr. Doug Moir, a cardiologist in Escondido seen with patient Doris Dunn, questions how long he can afford his practice under new mandates. Peggy Peattie - U-T

Worse is the hit to productivity. Doug says he once aimed to see four patients an hour for normal office visits. Now he struggles to see three each hour, and colleagues report much the same.

That 25 percent drop in productivity will surely shrink with time. Doug is testing voice-recognition software, for example.

And some doctors like the software, saying patients appreciate Obamacare's mandated printouts, which include visit summaries, test results and treatment plans.

The tech effect

Still, the mandates clearly shift advantage to large doctor groups and health systems that can amortize costs over more patients.

Technology - in the form of new drugs, devices and surgical techniques - has been a chief cause of soaring health costs in the U.S., according to a landmark 2001 study by Harvard health economist David Cutler and Stanford physician Mark McClellan.

The study found most medical technologies easily passed the cost-benefit test, giving people longer and better lives.

But information technology is not always so powerful. In the corporate world, fully half of all big IT projects fail to deliver promised benefits, authoritative studies have found.

Still, most experts see IT ultimately delivering productivity gains across the health care system.

Cutler, who was the senior health policy adviser to President Barack Obama, says doctors confront two basic facts: Information technology is here to stay, and prices for most procedures will remain frozen.

"The medical world is going IT, and this will be very hard for small physician practices," Cutler said recently via email. "Just as small retail stores had to find a niche they could fit in with bigger, IT-enabled competitors, so too will small M.D. practices. Undoubtedly, many will not survive."

In our conversation, Doug and Margaret Moir made it clear they aren't looking for pity.

They've done well, materially and spiritually. "We have a good life," she said.

Yet her frustration is palpable: "I don't think the general public has any idea their health care dollar doesn't go to the health care provider."

Her husband seemed mostly sad - and worried that patient care will suffer, because he enjoys helping people.

Success up in the air

As a small-business trend, the struggles of private medical practices are much like the decline of the local hardware store or the family farm.

But food is cheaper and better than it was a generation ago. And Home Depot has clearly cut my hardware costs and expanded my choices.

With research showing the American health system delivering lower quality and higher costs than other advanced nations, the success of the latest overhaul is not at all assured.

From age 5 to 35, my doctor in Kentucky was Ed Stratman, a World War II hero with warm hands, a steel-trap memory and astonishing diagnostic skills.

Today my "doctor" is Kaiser Permanente, a giant company that uses technology and standardized treatment to orchestrate a team of technicians, nurses and doctors.

In my case, both models delivered excellent care at reasonable cost.

Stratman, who also treated my parents and brothers, knew my history intimately, occasionally using a file folder to refresh his memory.

Kaiser communicates my particulars electronically, and someday it will use DNA to approximate Stratman's command of my family history.

Experts say the future belongs to the Kaiser model, although huge political and practical obstacles face a wholesale transition from the present, fee-based system to one that pays providers for keeping people healthy.

Cost-cutting is costly

On average, doctors still make excellent salaries. However, studies predict shortages as increasing hassles deter students from medical school. And politicians like to forget that cost-cutting is inherently costly for someone.

"What's happening is every day Americans get up hoping their health care spending goes down, but want their doctors to make more money," said Princeton economist Uwe E. Reinhardt. "If I reduce one person's health care spending, I've reduced someone else's income, and that's the doctors, medical-device companies, scientists, and all the other components of the health care system."

So far, nobody knows if the move to factory-style medicine will improve the quality or cost of care.

Yet there's no question that patients are losing something valuable. It's OK to be sad about this.

Correction:

A previous version of this column misstated a percentage; in the example above, doctors report that electronic systems have cut productivity by about 25 percent, and not 33 percent (which would be the increased labor component). Also, federal requirements and incentives for electronic health records were part of the economic stimulus package signed in 2009 by President Barack Obama.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter