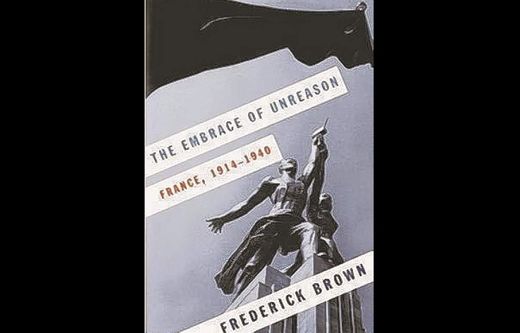

A victor splintered and embittered, careening into the Third Reich. In The Embrace of Unreason,

Frederick Brown weaves a warning for America from the story of the divided French.

It is hard to predict how much attention will be paid to the fact that this year will be the 100th anniversary of the outbreak of World War I. No event has ever shaken the world more severely, or had such far-reaching and long-lasting consequences. Indeed, we still live in its gigantic shadow, wrestling with problems that were left unsolved and are still not answered today, among them the tangled ethnic and religious hatreds in the Balkans and the failure to deal with the Ottoman Empire's possessions in the Middle East in a way that satisfied either their inhabitants or the "great powers."

I am particularly susceptible to accounts of that war and its consequences, perhaps because my father and my Uncle Zoltan fought in it, in the Austro-Hungarian Army, while my maternal grandfather fought on the other side, in the British Army. When my elders mentioned "The War," they invariably meant that of 1914-1918, even after 1939, for the Second World War was merely the continuation of the first, "an armistice of 20 years," as Marshal Foch had accurately predicted at the Versailles Peace Conference, with some changes of side.

No country on the Allied side - except Russia, which plunged into revolution, civil war, and enforced isolation in the wake of its astronomical losses in battle - suffered more than France, which had almost 1.4 million battlefield deaths between 1914 and 1918 in a nation of 40 million people. In 1918, Germany suffered the ghastly consequences of defeat; France suffered those of victory, the price of which was to divide and embitter French politics and culture, and lead to its defeat in 1940.

It is that phenomenon that Frederick Brown explores in his brilliant new book,

The Embrace of Unreason: France, 1914-1940. France had already been the victim of cultural clashes prior to the war that polarized the country as sharply as did our own civil war - between left and right, monarchists (both those who yearned for the ancienne régime and those who favored the Bonapartists), between those who believed in the innocence of Captain Dreyfus and those who believed in his guilt, between Catholics and non-believers, between those who wanted a bigger French army with which to confront Germany and those who feared the French army as a reactionary force in French politics, between Boulangists and anti-Boulangists...

Read more

here.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter