OF THE

TIMES

Heaven and hell are eternal places because they are always present at the extremes of human existence, for better or for worse. People are constantly choosing between them, although they are generally not conscious of that in an articulated manner.

listening to this dialogue from Neill Oliver reminded me of this interview from Planet Lockdown with Cathrine Austin Fitts, where she laid out the...

"China now holds a stunning 2,262 tonnes of gold" - LOL! What a freaking joke of a comment. Back in about 2000 I was intently reading the news...

...she can get away with anything... except her very, very long sojourn in hell, when she will move on from this life. Once there, nobody will...

Follow the money to follow the control. OOSA Is the scape goat of this control.

SOTT comment says it all.

To submit an article for publication, see our Submission Guidelines

Reader comments do not necessarily reflect the views of the volunteers, editors, and directors of SOTT.net or the Quantum Future Group.

Some icons on this site were created by: Afterglow, Aha-Soft, AntialiasFactory, artdesigner.lv, Artura, DailyOverview, Everaldo, GraphicsFuel, IconFactory, Iconka, IconShock, Icons-Land, i-love-icons, KDE-look.org, Klukeart, mugenb16, Map Icons Collection, PetshopBoxStudio, VisualPharm, wbeiruti, WebIconset

Powered by PikaJS 🐁 and In·Site

Original content © 2002-2024 by Sott.net/Signs of the Times. See: FAIR USE NOTICE

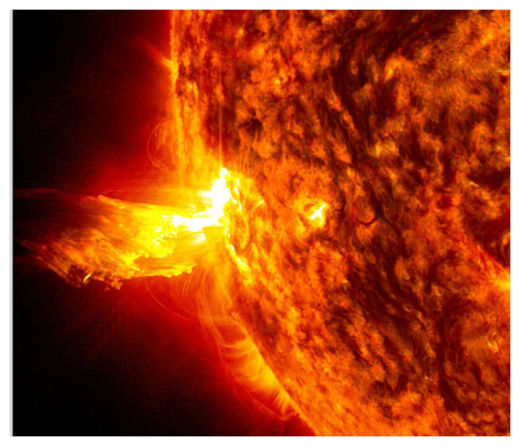

Depeding on the metrics used to quantify Solar Activity, Solar Cycle 24 is weaker than the 100 yr cycle, and even matches the 200 yr cycle (Dalton Minimum).

It is also doing something akin to the Maunder Minimum, which is diving back down at nearly the same slope it came up on.

And, it's doing some things nobody expected:

1.) Shrinking the umbral (darkest areas) of sunspots, which if continued will make it die off even faster (a la the last cycle before the Maunder Minimum).

2.) Failing to converge the North and South Sunspot belts.

It must be borne in mind that the telescopes used to observe in the early days were far inferior to the optics of even the 19th Century. And they did NOT count sunspots until the 1850's. They counted the Sunspot Groups, and Galileo started that.

What will the Sun do next?

Go half dark, as in the time of Justinian?

Go Maunder and give almost no spots for 80 years, save a few half-hearted sputters?

Go Dalton, and give few spots for 40 years?

Go Sporer or Wolfer Minimums, doing who knows what (we have no data on those times)

Go postal, sending out a monster flare to make up for the lack of other output (Svalgaard)?