"These civilian marriage certificates are not antiques or historical records. Few people take an interest in collecting them. But to some degree, they bear witness to historical changes in China," said Wang, president of the Luoyang Museum of Folk Customs in Luoyang City, central China's Henan Province.

Wang entertains a special affection for these certificates and has spent four years collecting them from various second-hand book markets and antique markets.

By now, he has a varied collection, including certificates for marriages, divorces, remarriages, and ghost marriages. A ghost marriage is a marriage in which one or both parties are deceased.

These certificates also give a glimpse into the lives of women in ancient China, when they were expected to practice the 'three obediences and four virtues'. A woman was supposed to obey her father before she got married, obey her husband while married and obey her son in widowhood. The four virtues included fidelity, physical charm, propriety in speech and efficiency in needle work.

"In feudal China, a marriage was arranged by parents between two families of equal social rank. The bride and bridegroom were supposed to match each other in their birthdates. A lot of rituals were also observed about a wedding. However, all that was still not enough to guarantee a happy marriage," said Wang.

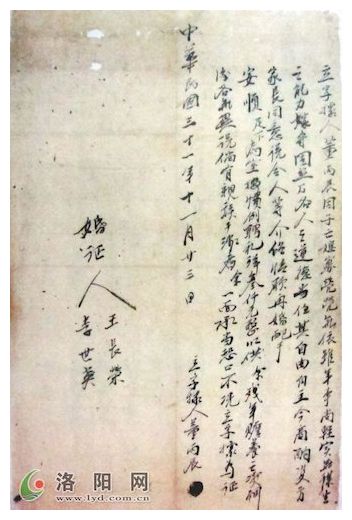

In Wang's keeping is a remarriage certificate signed by Dong Bingchen, a man who lived during the time of the Republic of China (1912-1949). The certificate, signed in 1942, states: "My widowed daughter-in-law is still very young and cannot support herself. She is free to get remarried and after negotiation, parents of the two parties have agreed to marry her to a man named An Shun."

"According to the local custom, the man should pay 3,000 silver dollars as the betrothal present so as to provide for my old age. I will not regret this in the future. If any family members have any objections, I will take full responsibility. I put it down in black and white as proof."

This remarriage certificate is quite moving. As a father-in-law, Dong was grieved over his son's death but was unwilling to see his young daughter-in-law live in widowhood.

"At the time, it was not easy for a father-in-law to make such a decision," said Wang. "The betrothal present is also in accordance with the traditional Chinese virtue of filial piety and caring for the elderly."

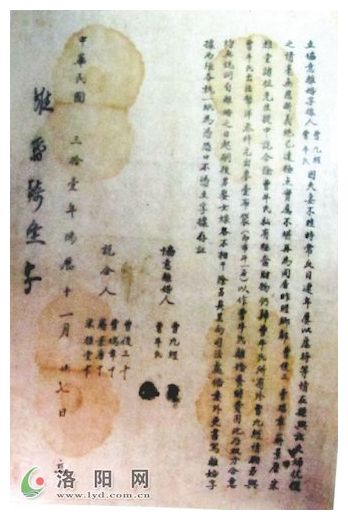

Another of Wang's certificates was also signed during the time of the Republic of China and states that, "The two parties Cao Jiujing and his wife Niu are on bad terms with each other. Cao has abused Niu for years. Their divorce file has been recorded by the county legal authority. The two have no feelings for each other and cannot live together."

"Fellow villagers Cao Junsan, Cao Ruizhang, Jiang Jingtang and Tang Yatang act as moderators. Apart from Niu's personal things, Cao is also willing to pay Niu 3,000 silver dollars and a 60-kilogram bag of wheat as spousal support."

"The two parties have signed this certificate voluntarily. In the future, the two are prohibited from interfering in each other's new marriage. Apart from the official divorce file, the two parties have signed a divorce certificate in duplicate, each having one copy."

This paper has considerable significance because of the use of the word 'divorce'. In feudal China, gender inequality meant that a husband could repudiate his wife but a wife could not divorce her husband. As a result, ancient Chinese laws did not use the word 'divorce' but 'end the marriage', 'abandon', 'repudiate the wife' and other similar words.

Thus, this divorce certificate signed in 1942 shows that people were beginning to change their traditional mindsets and become more open and progressive.

In feudal society, it was also rare for a woman to get any form of assets after being left by her husband. So although ownership of her own personal items, as well as 3,000 silver dollars and a bag of wheat may seem meager to modern people, it actually shows that women's status was beginning to improve at that time.

An Unusual Marriage Certificate

Another marriage certificate, written on a piece of red paper, was presented in the name of the bridegroom's father, Zhang Bingyao, to the female party.

The bridegroom was called Zhang Zhengwu and the name of the female party was not stated on the certificate.

The certificate reads that the two parties match each other in their birthdates, so the male party is to present the betrothal gifts to the female party on October 7 and hold the wedding on October 13 according to the Chinese lunar calendar.

On the wedding day, relatives and friends born in the years of the Chinese Zodiac Pig, Goat and Rabbit were not supposed to be present.

"The certificate wasn't marked with a date but was presumably created at the end of the Qing Dynasty. In feudal society, people didn't get their marriage certificates from authorities because marriages were arranged by parents and matchmakers," said Wang.

"Even today, such marriage customs are observed in certain areas of China," added Wang.

A Ghost Marriage

One of the most interesting certificates in Wang's collection is one that shows a ghost marriage taking place.

According to the certificate, a person named Liang Ruyi had a cousin who died in an accident while a daughter-in-law of the Liang family also died with no offspring. Under such circumstances, a ghost wedding was held for the two.

"People had shorter life spans at the time and some young men or women who were engaged and died for some reason before they got married would be 'married' after their deaths because their families believed that they would bring bad luck to the family otherwise," said Wang.

Ghost marriages were also held for people who died at an early age before getting engaged. "Parents would also select a spouse and hold a wedding for them to fulfill their parental responsibilities and show their love for their children," added Wang.

In feudal China, ghost marriages were a fairly normal occurrence. For example, Cao Cao (155-220), a warlord and the penultimate Chancellor of the Eastern Han Dynasty (25-220), gave betrothal gifts to a dead woman to make her the wife of his favorite son, Cao Chong (196-208), who died at the age of 13.

In addition, ancient people had a superstitious belief that a single tomb would have a bad influence on the fortune of a family. Thus, in order to earn more money, some geomancers urged people to organize ghost marriages.

Nowadays, such superstitious acts still persist in more remote areas of China. Recent years have seen female dead bodies stolen in some areas in northwest China's Shaanxi Province and even extreme cases in which young women have been killed to be married off to dead men.

"It's a pity that feudal superstition has produced a far-reaching poisonous impact in some areas," concluded Wang.

Source: Orient Today/Translated and edited by Womenofchina.cn

had become subservient to men but further back in time is the discovery of a secret writing developed by women for women. This amazing Nushu

[Link]