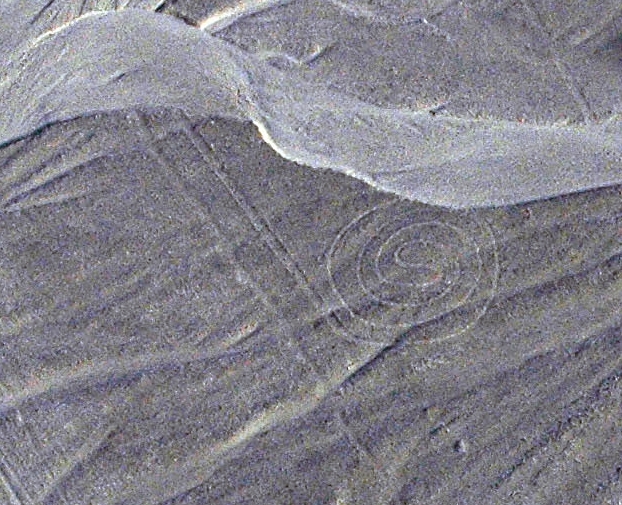

Completely hidden in the flat and featureless landscape, the labyrinth was identified after a five-year investigation into the arid Peruvian coastal plain land, about 250 miles south of Lima, where the mysterious geoglyphs are located.

"As you walk it, only the path stretching ahead of you is visible at any given point," Clive Ruggles of the University of Leicester's School of Archaeology and Ancient History, said.

Ruggles and colleague Nicholas Saunders of the University of Bristol's Department of Archaeology and Anthropology walked more than 900 miles of desert, tracing the lines and geometric figures carved between 100 B.C. and 700 A.D. by the Nasca people. They reported their findings in the December issue of the journal Antiquity.

Also known for their obsession over trophy heads - - they boasted the largest collection of human heads in the Andes region of South America -- the Nazca flourished in Peru between the first century B.C. and the fifth century A.D. and slid into oblivion by the time the Inca Empire rose to dominate the Andes.

First discovered by Ruggles when he spent a few days on the Nazca desert back in 1984, the labyrinth lies in the midst of the study area.

"Factors beyond my control brought the 1984 expedition to an abrupt halt. It was only 20 years later that I eventually had the opportunity to return to Nazca, relocate the figure and study it fully," Ruggles said.

He added that the only way to become aware of the labyrinth is to walk its 2.7-mile length through a disorienting twisting path.

Indeed, the labyrinth features 15 corners that would bring the walker away from and towards a large hill before turning into a spiral passageway. Walking the entire path would have probably taken about an hour.

"I was almost certainly the first person to have recognized it for what it was," Ruggles said.

The labyrinth's well-preserved edges suggest it was walked by a few people in single line. Unfortunately, there is no way to know the meaning of the structure and how it was used.

According to the researchers, walking the lines has provided an important source of information to better understand the enigmatic desert drawings.

Recognizable only from the air, the lines, geometric designs and images of animals and birds, some up to 900 feet long, have been a source of mystery since their discovery nearly a century ago.

Called anything from ancient calendars to landing strips for alien spaceships, the lines were also linked to water deities, suggesting that they marked sacred paths and places where people went to worship.

After studying the integrity of many lines and figures within a 50-square-mile area, Ruggles and Saunders concluded that the meandering and well-worn trans-desert pathways were most likely created for functional purposes. On the contrary, the famous arrow-straight lines and geometric shapes appear to have had a spiritual and ritual purpose.

"It may be, we suggest, that the real importance of some of these desert drawings was in their creation rather than any subsequent physical use," Ruggles said.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter