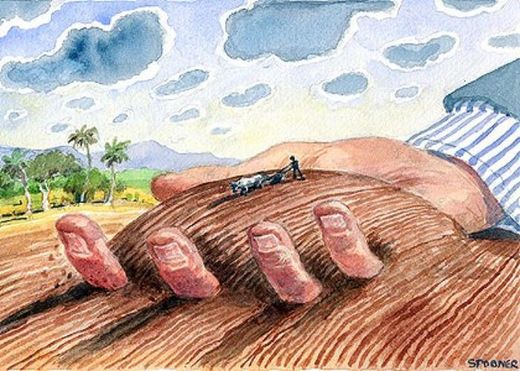

Amid warnings that land deals are undermining food security, the head of the UN's Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) has compared "land grabs" in Africa to the "wild west", saying a "sheriff" is needed to restore the rule of law.

José Graziano da Silva, the FAO's director general, conceded it was not possible to stop large investors buying land, but said deals in poor countries needed to be brought under control.

"I don't see that it's possible to stop it. They are private investors," said Graziano da Silva in a telephone interview. "We do not have the tools and instruments to stop big companies buying land. Land acquisitions are a reality. We can't wish them away, but we have to find a proper way of limiting them. It appears to be like the wild west and we need a sheriff and law in place."

Large land deals have accelerated since the surge in food prices in 2007-08, prompting companies and sovereign wealth funds to take steps to guarantee food supplies. But, four to five years on, in Africa only 10-15% of land is actually being developed, claimed Graziano da Silva. Some of these investments have involved the loss of jobs, as labour intensive farming is replaced by mechanised farming or some degree of loss of tenure rights.

Oxfam said the global land rush is out of control and urged the World Bank to freeze its investments in large-scale land acquisitions to send a strong signal to global investors to stop.

Graziano da Silva, who was in charge of Brazil's widely praised "zero hunger" programme, expressed his frustration at the slow pace of creating a global governance structure to deal with land grabs, food security and similar problems. In 2008, the UN secretary general, Ban Ki-moon, created a high-level task force on food security on which Graziano Da Silva serves as vice-chairman.

In May, the committee on world food security (CFS), a UN-led group that includes governments, business and civil society, laid the groundwork for a governance structure for food by endorsing voluntary guidelines on the responsible governance of tenure of land, fisheries and forests.

Comment: Voluntary guidelines? Do they really think rapacious corporate interests will follow those?

Tenure has important implications for development, as it is difficult for poor and vulnerable people to overcome hunger and poverty when they have limited and insecure rights to land and other natural resources. But the guidelines took years to negotiate and lack an effective enforcement mechanism because they are voluntary. The CFS is an unwieldy group but has the virtue of inclusivity.

"It took two years to discuss the voluntary guidelines and now we face another two years of negotiations on the principles for responsible agricultural investments," said Graziano da Silva. "We need to speed up the decison-making process without losing the inclusivity model."

The FAO director general said he is doing his best to bring about more co-ordination among the different institutions concerned with food security and suggests the FAO act like an executive arm of the CFS, trying to implement its decisions.

Others share his frustrations. Olivier De Schutter, the UN special rapporteur on the right to food, acknowledges the importance of the CFS voluntary guidelines, but points out the lack of an effective enforcement mechanism. He argues that governments in sub-Sahran Africa or south-east Asia with poor governance, or tainted by corruption, will continue to seek to attract investors at all costs.

Comment: Uhm, isn't that putting the cart before the horse? The investors are clearly more at fault here.

"The international community should accept it has a role in monitoring whether the rights of land users, as stipulated in the guidelines, are effectively respected," De Schutter told the Guardian. "Since there is no 'sheriff' at global level to achieve this, at the very least, the home states of investors should exercise due diligence in ensuring that private investors over which they can exercise control fully respect the rights of land users. Export credit agencies, for example, should make their support conditional upon full compliance with the guidelines, and in the future, the rights of investors under investment treaties should be made conditional upon the investors acting in accordance with the guidelines."

For Graziano da Silva, the key is the implementation of the voluntary guidelines at country level; he is encouraged by growing public interest and awareness of the issue. He points to Uruguay as an example of a government prepared to stand up to international land investors - "perhaps the best sheriff" on land deals.

"They have very good laws on land acquisitions," he said, but acknowledged that most countries where land grabbing takes place have little consultation with farmer organisations or have weak or repressive governments.

As for the perennial debate on the respective merits of large- and small-scale farming, the FAO boss said Africa had room for both, adding that Brazil had managed it.

Comment: Yes, Brazil managed it by limiting the ability of international corporate entities to pillage at will.

Brazil to further limit foreign ownership of land

"In some areas of Africa - Mozambique and South Africa - there is scope for large farms, but this approach is only valid for some grains, where the entire cycle is mechanical," he said. "But this is not suitable for fruits, vegetables or many other local products. Cassava has nothing to do with mechanised agriculture and efficiency does not mean big scale. It's the way you combine crops, the use of water you have available. In Africa today, efficiency means better seeds rather than big tractors. The two models have been there forever in agriculture. Sometimes big-scale will provide exports, but local markets are based on small-scale agriculture."

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter