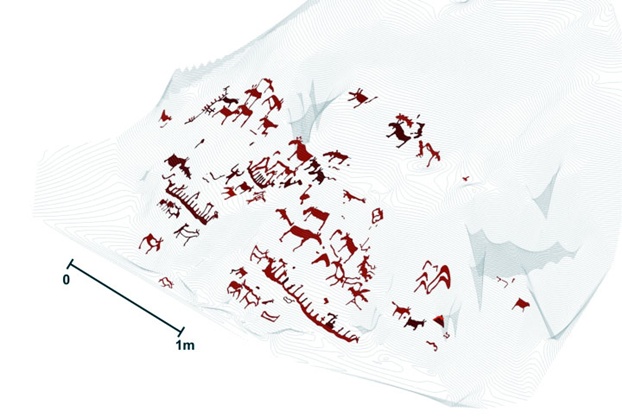

Using computer modeling, Mark Sapwell, a Ph.D. archaeology student at Cambridge University, analyzed some 3,500 rock art images from Nämforsen in Northern Sweden and Zalavruga in Western Russia.

"Although this rock art has been documented from the early 1900s, the modeling has allowed a unique look at the interesting way these images have been arranged and accumulated over time," Sapwell told Discovery News.

Carved from about 4000 B.C. up to the Bronze Age, the rock art shows animals, people, boats, hunting scenes -- even very early centaurs and mermaids. It was produced by generations of semi nomadic people, who lived more inland in winter to hunt elk, and then occupied areas closer to coasts and rivers to fish.

As they were located in important and prominent locations on river crossroads, the rock art landscapes were likely very visible points where passing travellers would take notice of the traces of people who came before them, adding their own mark on the world.

"The rock art we see today is the result of a culmination of many repeated acts of carving, each responding to each other over time. Like a Facebook status invites comment, the rock art appears very social and invites addition," Sapwell said.

Usually clustered on the granite rocks, the images ranged from groups of one to two images to rock art panels with over 500 images. Larger clusters represented a greater response and conversation between people.

"Additions to these works were exacting replications, stamps of approval -- a primitive 'like,'" Sapwell said.

"One exciting part of the study is that the preference towards these popular images change through time. A very big change at Namforsen is the shift from elk to boat images, as if the 'topic to talk about' shifted from land to water," Sapwell said.

The shift is dated to around 2000-1800 B.C., a time when travel and long-distance exchange between communities was becoming more important.

Another interesting part of the find is the importance of unique forms of hybrid imagery (for example a half-man half elk, or half-man half-boat), which was tried out in the early periods, but became less popular from around 3500 B.C.

"So generally, what we see in these landscapes are very interesting cases where through prehistory, particular themes in everyday life become worth commenting on. A little like the fashions of Facebook comments, these topics are seen to fall in and out of favor," Sapwell said.

According to Sapwell, the enormous natural canvases attracted so much interest because their social network power was well understood by early Bronze Age people.

"Like today, people have always wanted to feel connected to each other -- this was an expression of identity for these very early societies, before written language," Sapwell said.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter