As Scioto County Prosecutor Mark Kuhn kicked off the process of selecting a jury for a drug-related murder trial last year, he asked those selected randomly to raise their hands if someone in their family or in a friend's family had a drug problem.

One by one, all 31 potential jurors stuck their hands in the air.

Even for a seasoned prosecutor who has seen thousands of drug cases come through the Scioto County system in his six years on the job, it was a stunning verdict about the depth of the drug problem in the county.

"That was simply unbelievable," Kuhn said, shaking his head on a recent morning as he stood in the hallway at the Scioto County Courthouse, a manila folder full of arraignments tucked under his arm. A courtroom full of defendants awaited him -- most of his cases typically will somehow involve prescription drug abuse.

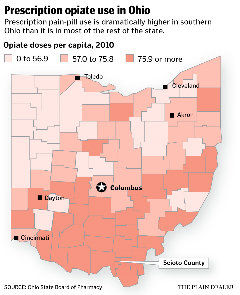

Such is life in Scioto County, a Southern Ohio county on the Ohio river where a prescription drug epidemic crosses all socioeconomic lines, wrecking young lives from ramshackle trailer parks to cushy suburban homes. The pain pills come in varying forms and dosages, but there is no question which one is king -- OxyContin, the fifth most prescribed drug in the world.

Fueled in part by a half-dozen legally operating pain clinics that dot Scioto County, doling out an estimated 35 million pills a year, the prescription drug problem has taken its toll in numerous ways: spiraling hepatitis C rates, a thriving pill-based underground economy and nearly one in 10 babies born addicted to drugs.

But nowhere does it hit harder than in the fatal overdose deaths this county has seen -- more than 120 in the last decade and more every year. It's common enough that locals even have a name -- the Portsmouth Cocktail -- for the lethal combination of opiates, sedatives and muscle relaxants that bring the coroner's van.

It takes about 20 paces to walk the length of a memorial set up in a downtown Portsmouth department store window. It's sponsored by a group of family members of people who have died of prescription drug overdoses called SOLACE -- Surviving Our Loss And Continuing Everyday -- and it's a grim roll call that grows longer each year.

Walk the length of that shrine and the names and pictures of about three dozen mostly young Scioto County residents stare back at you.

Up on the wall is Barbara Howard's daughter, 34-year-old Leslie Cooper, who died in 2008 after she visited a Scioto County pain clinic. A round-faced woman with short, spikey graying hair, Howard begins to sob as she tells the story of how her daughter became addicted to pain pills after multiple surgeries.

"I feel like these pain clinics that are able to keep doing this are no different than Doctor Kevorkian. These doctors are killing our young people for money -- that's it," she said tearfully in a small conference room at the Portsmouth health department. "The doctor that prescribed my daughter all of those medicines, she was just a number to him. Two-hundred fifty dollars--that's what he valued my daughter's life, that's what I feel like."

She wipes at the tears in her eyes and clutches tightly the hand of JoAnna Krohn, the founder of SOLACE who began the group after the death of her 18-year-old son Wesley Workman.

A handsome kid who was a star high school football player, Workman died in April 2008 of a self-inflicted gunshot wound with OxyContin in his system. Her son had become a pain pill dealer for the easy money, his mother said. And he had armed himself after previously being robbed by people seeking drugs and cash.

When Krohn began the group 10 months ago, she said there were seven people at the first meeting. "Now, it's not unusual for 40 people to come to our meetings," she said. "And even with all of the people that come to the meetings, there are three or four times that amount that haven't come to the point of trying to do something about it."

The first time Ed Hughes ever heard of OxyContin was in 1997.

The executive director of The Counseling Center, the largest residential treatment center in Portsmouth, Hughes heard a few clients mention it to a local reporter doing a story about people seeking treatment around Christmas.

In the 14 years that have passed since OxyContin abusers began appearing at his clinic, Hughes said those seeking addiction for opiates has risen sharply from one in 20 people seeking drug treatment to nearly all.

"Now, 85 percent of the people who come in our door" are addicted to opiates, Hughes said. "Heroin is starting to show up more and more because we are starting to see that transition take place from an expensive drug like OxyContin to a cheaper drug in terms of heroin."

Hughes said the number of people seeking treatment is "off the charts" and has risen by 50 percent over the last decade, creating a long waiting list for his programs. He estimates that as many as 5,000 to 6,000 people in the Portsmouth area need drug treatment -- which would equal a four-year waiting list if they all came for help to The Counseling Center, where 1,500 patients are treated a year.

Hughes said opiate addictions cause "a level of chaos and craving and struggle just to get sober" that makes the addictions tough to treat.

Hughes said only about one in four people will recover from opiate addiction after the first round of treatment and stay clean for the rest of their lives. But that number rises to 85 percent if they go through the center's long-term program that includes residential care, long-term transitional services and even a job for a lucky few at a screen printing company the center operates.

Along with the steady rise in pain pill addicts, Hughes has observed another alarming trend: a younger and increasingly female population of users.

"This drug is making its way into the youth population faster than any drug that we have ever seen," Hughes said, recalling an incident last school year in which nine middle school students were arrested at a local school for dealing OxyContin.

Because pain pills are legally prescribed, they have an air of legitimacy with young people, he said.

"Kids tell us they experiment with this drug because they heard bad things about alcohol and marijuana," Hughes said. "But this came out of Grandma's medicine cabinet -- a doctor prescribed this. To a child, that just seems much safer and having much less risk."

Representative of the younger and female patient profile is Cala McWhorter, a 21-year-old from Ross County who is finishing up a four-month stay at a residential program for women. She joined the program when a probation violation from a theft case forced her to take a second look at her life.

At age 15, McWhorter said she moved from experimenting with pot and alcohol to doing cocaine and mixing it with pain pills. A high-school dropout, she was living with a boyfriend involved in drugs, so her parents weren't aware of the lifestyle she was beginning to lead.

"When I started off, everybody was basically giving me the pills -- I didn't have to give them any money," she said. "They were basically trying to get me in to where I was addicted, and then they stopped feeding them to me and I had to find money for them every day."

Stealing from friends and family members and pawning her possessions to stay high snorting OxyContin, McWhorter said she became lost in a drug haze.

"I used to use them so much that if I didn't have them then I didn't feel normal," she said. "I had to take them to feel normal, not to feel high."

Told she faces long odds to kick her addiction, the world-weary McWhorter acknowledges it will be tough.

"Yeah I know, I know," she said. "I'm not going to be able to slack, I'm not going to be able to take a break. You didn't take a break when you were using. You didn't take one day off because you didn't feel like getting high. I'm just going to have to keep at it, all day."

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter