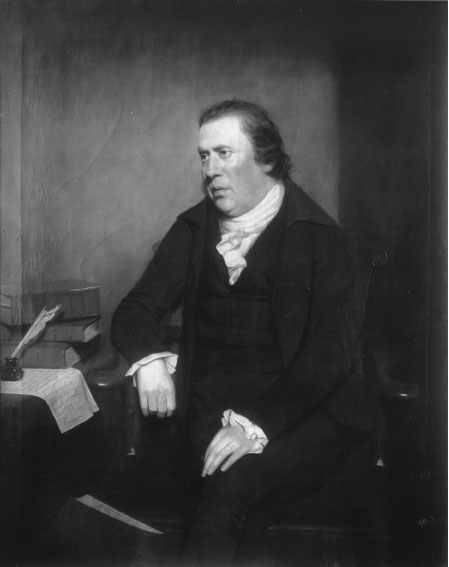

They are giants of medicine, pioneers of the care that women receive during childbirth and were the founding fathers of obstetrics. The names of William Hunter and William Smellie still inspire respect among today's doctors, more than 250 years since they made their contributions to healthcare. Such were the duo's reputations as outstanding physicians that the clienteles of their private practices included the rich and famous of mid-18th-century London.

But were they also serial killers? New research published in the Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine (JRSM) claims that they were. A detailed historical study accuses the doctors of soliciting the killing of dozens of women, many in the latter stages of pregnancy, to dissect their corpses.

"Smellie and Hunter were responsible for a series of 18th-century 'burking' murders of pregnant women, with a death total greater than the combined murders committed by Burke and Hare and Jack the Ripper," writes Don Shelton, a historian. "Burking" involved murdering people to order, usually for medical research.

According to Shelton, the two men were between them responsible for the murders of 35-40 pregnant women and their unborn children. Acting separately, and using henchmen to deliver their supply, they organised a killing spree in London between 1749 and 1755 and, after a period of inactivity enforced by mounting suspicion about the source of their corpses, resumed between 1764 and 1774. Motivated by ego, personal rivalry and a shared desire to benefit from being acclaimed as the foremost childbirth doctors of their time, Hunter and Smellie sacrificed life after life in their quests to study pregnancy's physical effects and to develop new techniques, the author says. "Although it sounds absolutely incredible, the circumstantial literary evidence suggests they were most likely competing with each other in experimenting with secret caesarean sections on unconscious, or freshly murdered, victims, with a view to extracting and reviving the babies," Shelton told the Observer.

Shelton examined the men's anatomical atlases, containing detailed images of pregnant women who had been opened up, and medical literature and the causes of death in London at the time. Glasgow's Hunterian museum and gallery is named after Scottish-born Hunter, who in 1762 became physician to Queen Charlotte, wife of George III. He helped her to deliver the future king, George IV.

Smellie, a fellow Scot, is no less distinguished. From Witchcraft to Wisdom, a textbook on the history of obstetric and gynaecological medicine, hails him as "the greatest obstetrician in the history of British obstetrics". He has also been called "the father of British midwifery".

Shelton, though, regards the duo as on a par with Burke and Hare, who murdered 17 citizens of Edinburgh in 1827 and 1828, selling their remains to a local anatomist. The London of Hunter and Smellie's time was unhealthy and semi-anarchic, and early death from disease was widespread, as was grave robbing. In his JRSM paper, Shelton claims to prove that the rival doctors could not have obtained their supply of corpses by any other means than murder. It was rare for mothers-to-be to die or be murdered soon before they were due to give birth, says the historian. People from poorhouses who died were usually old, unwell or children. Thus the grave robbers of the time could not have fulfilled the obstetricians' need for such a specific type of female, concludes Shelton.

"There is great suspicion about the abundance of undelivered ninth-month corpses procured, dissected and depicted in the anatomical atlases of Smellie and Hunter," writes Shelton. "The impossibility of supply from random resurrections, taken with a careful analysis of events, and of 18th-century medical literature, shows compelling evidence for burking."

By 1755 rumours were circulating that the women in Smellie's journal had been murdered, and associates began pressing him on their origins. "As a result Smellie and Hunter both halted their research, both presumably fearing trial and execution," although Hunter - who used his links to powerful families to ensure no investigation was ever undertaken - resumed ordering murders, about once a year, in 1764, Shelton adds.

Anthony Kenny, a gynaecologist in London for 40 years until his retirement in 2007, said: "These two guys are my heroes. The idea that they could have been involved in the murder of subjects is absolutely staggering." Kenny is now the curator of the museum of the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists. "They were the first proper obstetricians in the country because of their pioneering work practising what was then still a new branch of medicine."

While Kenny describes Shelton's paper as "extremely impressive" in its research, he cannot believe that his heroes were guilty of such terrible crimes. The trade in corpses was very lucrative and probably attracted unsavoury, unscrupulous characters, he pointed out. "And it could be that they didn't make proper inquiries as to the origins of the bodies, and so may not have known that the women were murdered."

Ludmilla Jordanova, a professor of modern history at King's College London who specialises in the history of medicine, says Shelton's assertion that Hunter and Smellie could not have come across so many dead pregnant women from any other source as "a striking claim. Important research... is revealing the complexities of anatomical activities in 18th-century London. This is an exciting and controversial area of historical investigation, and it invites more meticulous research and judicious research."

Shelton says his research "turned out to be a bit like a thinking person's Da Vinci Code, but in this case involving facts, not fiction. Although the conclusion of burking is shocking, to quote Sherlock Holmes, 'When you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, is the truth.'"

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter