Las Vegas can be a magical place. It certainly is for Penn and Teller, who have been performing magic in their own Las Vegas theatre for almost eight years.

The house is packed every night - a testament to both Penn and Teller's draw . . . and to the universal appeal of magic itself.

"What makes for a successful trick?" Blackstone asked Teller, who never says a word on stage. He broke his silence for our interview (but insisted that we not show his moving lips).

"The core of a successful trick is an interesting and beautiful idea," he said, "that taps into something that you would like to have happen. One of the things we do in our live show is I squeeze handfuls of water and they turn into cascades of money. That's an interesting and beautiful idea.

"The deception is really secondary," Teller said. "The idea is first, because the idea needs to capture your imagination."

"Magic does something really that no other kind of performing art can do, and that is, it manipulates the here and now - our reality," said Noel Daniel of Taschen Books in Los Angeles. She has just edited a book on the history of magic, Magic: 1400s - 1950s.

"When we're watching a movie, we don't think that what we're watching is real; we know it's not," said Daniel. "We're staring in a dark room, at a lit screen. But in magic, we're watching someone manipulate a coin, or cards, or fire, or sawing a woman in half, right on stage, in front of our very eyes. And this is the power of magic."

Daniel spent over a year compiling old, rare images of magic through the ages.

She says the first magic performance is thought to have been in Egypt around 2000 B.C.: A shaman proving his powers to the pharaoh.

"He took a duck, decapitated its head, and then restored the head to the living animal," said Daniel. "Of course, this impressed the king very much!"

But the impression made by magicians has not always been as positive.

During the Middle Ages in Europe, they were sometimes accused of witchcraft, and were banned from certain towns. Only by the late 16th century did suspicion give way to applause, as magic assumed its place among the performing arts.

For centuries to follow, crowds would watch in wonder, consumed by a question that still resonates today:

"How does the magician get the audience member to believe? And that's where the magic takes place," said Daniel.

How magic works - and why we keep falling under its spell - is now the subject of some serious investigation . . . not in a magician's workshop, but at a leading center for neurological research, the Barrow Neurological Institute in Phoenix, Ariz.

There, two Harvard-educated neuroscientists came to the humbling realization that magicians sometimes understand the mysterious workings of the human brain more than they do.

"The more we thought about it, the more we realized that magicians actually had skills that we didn't have, as scientists," said Dr. Stephen Macknik.

Dr. Susana Martinez-Conde said what they are trying to get at is "why the tricks work in the mind of the spectator, and what are the brain principles behind it."

So in the interest of neuroscience the two researchers have been collaborating with several magicians, including Teller.

"that's what the art of magic is really for," said Teller. "It's the playground for perceptions."

Mac King, who does a comedy-magic act in Las Vegas, has been helping with the research, too.

We asked King to come to the Barrow Neurological Institute, to show us how the magicians and neuroscientists are working together.

Blackstone watched King perform, while wearing a device that tracked his eyes.

"Wanna see a trick?" said King.

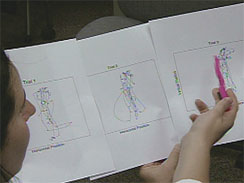

A graph of Blackstone's eye movements (left) showed how King manipulated his attention. No wonder he was fooled - he was looking in all the wrong places.

Dr. Martinez-Conde showed him where his eyes tracked. "Here, again, you're lost," she said. "Now your eyes are following a different pattern - you are at a loss, you don't know what to do."

"You think you can see everything all at once, when in fact, you can't," said Dr. Macknik. "That's an illusion that's created by your brain, and it allows us to navigate the world normally. So, the fact is that magicians are able to take advantage of that by knowing that you can only focus in one place while they do something somewhere else."

Teller thinks a lot about how magicians manipulate the brain to make us think we see things we really don't see - like misdirecting viewers from where he's holding a ball. "What's important is that your attention is going up there, not [seeing] that, you know, the ball is secretly hidden in my hand."

He demonstrated by showing how he'd tightly hold his fist - "more tightly than I would normally . . . so that you see the strain in my fingers" - to help convince the audience the ball IS in his hand.

He convinced Blackstone: "Every time you've done that I still imagine that it's going into your other hand," he laughed.

Teller is one of five magicians who, with Macknik and Martinez-Conde, co-authored an academic article on the science of magic last year.

Mac King, who also contributed, says magicians sometimes manipulate our minds, simply by aiming at our funny bone.

"If you want to get away with something, make somebody laugh," King said. "'Cause, I mean, when you're laughing, you can't pay attention to the secret little thing I need to do."

Drs. Martinez-Conde and Macknik, who drew some 7,000 neuroscientists to a recent conference where they discussed magic, say there's more to their work than sheer "gee whiz."

For one thing, it could change the way disorders like autism are diagnosed.

"We predict that autistics will detect the method in a magic trick better than someone with a Ph.D," Macknik said. "Autistics are people with deficits in joint attention, so they not only can't pay attention very well to people and where they're supposed to pay attention, but they're kind of repulsed by it.

"Therefore, they're paying attention to the things that the magician doesn't want 'em to be paying attention to."

"So what we have proposed is that one can use magic tricks as a tool for early diagnosis of autism," said Martinez-Conde.

Whether their research will achieve this ambitious goal remains to be seen.

For now, what's certain is that scientific analysis of magic poses an essential question for those who make a living at it:

"Does it ruin any of that magic to boil it down to neurons and the ways connections are made between the eyes and the brain?" Blackstone asked.

"It makes it better," said Teller. "Some people believe that scientists are out to take away the mystery. And really all they're doing is going deeper into it, getting to the more real, more deep, you know, more profound mysteries.

"The deeper you go into a mystery, the deeper mystery always becomes."

Comment: Read also, The Art of Deception, for a view on how the evil magicians of our times use their tricks to control us and render us helpless and hopeless under their spellbinding lies.