|

| ©NASA |

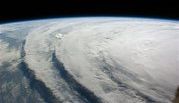

| Hurricane Ike as viewed from International Space Station. |

Ike's 105-mph winds and potential 50-foot waves stopped the Coast Guard from attempting a risky helicopter rescue of 22 people aboard a 584-foot freighter that broke down in the path of the storm about 90 miles southeast of Galveston, Chief Petty Officer Mike O'Berry said.

O'Berry did not provide the name of the ship, which was hauling petroleum coke used to fuel furnaces at steel plants, or details on where it was headed.

Ike's eye was forecast to strike somewhere near Galveston late Friday or early Saturday, but the massive system was already buffeting Texas and Louisiana, causing flooding along the Louisiana coast still recovering from Labor Day's Hurricane Gustav.

The National Weather Service warned residents of smaller structures on Galveston they could "face certain death" if they ignored an order to evacuate; most had complied, along with hundreds of thousands of fellow Texans in counties up and down the coastline.

Evacuation orders also were in effect for low-lying sections of the Houston area. In Surfside Beach, police were using a dump truck to try to reach flooded residences and any stubborn people who had refused to leave.

Officials said inland residents should not flock to the roadways en masse, creating the same kind of gridlock that cost lives - and a little political capital - when Hurricane Rita threatened Houston in 2005.

"It will be, in candor, something that people will be scared of," Houston Mayor Bill White said. "A number of people in this community have not experienced the magnitude of these winds."

The decision is a stark contrast to how emergency management officials responded to Hurricane Rita in 2005. As the storm closed in three years ago, the region implemented its plan: Evacuate the 2 million people in the coastal communities first, past the metropolis of Houston; once they were out of harm's way, Houston would follow in an orderly fashion.

But three days before landfall, Rita bloomed into a Category 5 and tracked toward the city. City and Harris County officials told Houstonians to hit the road, even while the population of Galveston Island was still clogging the freeways. The evacuation itself wound up far more dangerous than the storm: 110 people died during the effort, while the eventual Category 4 storm killed nine.

Residents were scurrying to get ready for Ike, and hardware stores put limits on the number of gas containers that could be sold. Batteries, drinking water and other storm supplies were running low, and grocery stores were getting set to close.

"We're faced with devastation of a catastrophic range," said Randy Smith, the police chief and a waterfront property owner on Surfside Beach, just down the coast from Galveston and a possible landfall target. "I think we're going to see a storm like most of us haven't seen."

Friday morning, Houstonians streamed in and out of a Randalls grocery store near downtown, carts filled with last-minute supplies such as water and Wheat Thins. Ken Wilson, 51, cut short a vacation to California to return home and ready for Ike. He loaded eight gallons of water into his car trunk before heading home to ride out the storm with his wife.

Wilson said it was too late for him to board up his house, though he had stocked up on ice and batteries.

"We'll just tape up to keep things from flying around. I'm apprehensive about how high the winds are going to be, and windows breaking," he said, but still: "What's the philosophy? Run from the water, shelter from the wind? If it's wind: Hunker down."

Texans were getting hit from both sides, as the remnants of Tropical Storm Lowell, a Pacific system, dumped nearly 8 inches of rain on Lubbock in 24 hours, flooding homes and roads. Some businesses closed, and Texas Tech University and other schools canceled Friday classes. Ike would be the first major hurricane to hit a U.S. metropolitan area since Katrina devastated New Orleans three years ago. For Houston - a city filled with gleaming skyscrapers, the nation's biggest refinery and NASA's Johnson Space Center - it would be the first major hurricane since Alicia in August 1983 came ashore on Galveston Island, killing 21 people and causing $2 billion in damage.

Galveston, a barrier island and beach town about 50 miles southeast of downtown Houston, was the scene of the nation's deadliest hurricane, the great storm of 1900 that left at least 6,000 dead.

Ike swelled into a huge storm, slinging 75 mph winds up to 120 miles from its center. That meant a direct hit on Galveston could still mean hurricane-force winds affecting a stretch of coast halfway to Corpus Christi and well into Louisiana.

The storm is so big, it could inflict a punishing blow even in those areas that do not get a direct hit. Forecasters warned because of Ike's size and the shallow Texas coastal waters, it could produce a surge, or wall of water, 20 feet high. It could also dump 10 inches or more of rain.

If the storm stays on its projected path, it could head up the Houston ship channel and through Galveston Bay, which Homeland Security Secretary Michael Chertoff called a nightmare scenario.

At 8 a.m. EDT Friday, the storm was centered about 230 miles southeast of Galveston, moving to the west-northwest near 13 mph. Hurricane warnings were in effect over a 400-mile stretch of coastline from south of Corpus Christi to Morgan City, La. Tropical storm warnings extended south almost to the Mexican border and east to the Mississippi-Alabama line, including New Orleans.

The oil and gas industry was closely watching the storm because it was headed straight for the nation's biggest complex of refineries and petrochemical plants. The upper Texas coast accounts for one-fifth of U.S. refining capacity. Some service stations in the Southeast were limiting customers to 10 gallons of gas to guard against running out.

___

Associated Press writers Kelley Shannon in Austin, Paul Weber and Regina L. Burns in Dallas, Juan A. Lozano and John Porretto in Houston, and Allen Breed and video journalist Rich Matthews in Surfside Beach contributed to this report.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter