On Monday, Bob Lanz used a 22-foot aluminum flatboat to navigate through downtown Oakville, where water reeked of pig feces and diesel fuel.

"You can hardly stand it," Lanz said as he surveyed what remained of his family's hog farm. "It's strong."

LeRoy Lippert, chairman of emergency management and homeland security in nearby Des Moines County, warned people to avoid the floodwaters: "If you drink this water and live, tell me about it. You have no idea. It is very, very wise to stay out of it. It's as dangerous as anything."

In addition to the poison in the water, there are mosquitoes - millions of them spawning in acres of standing water.

"We have just begun to fight," Gov. Chet Culver said. Two more deaths were reported Monday, including a woman whose car was hit by a National Guard truck, bringing the state's death toll to five.

Also Monday, the American Red Cross said its disaster relief fund has been completely spent, and the agency is being forced to borrow money to help flood victims throughout the Midwest.

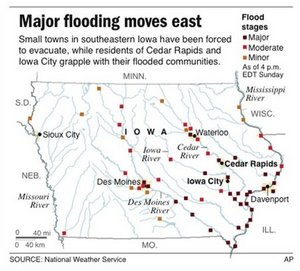

In the college town of Iowa City, damage appeared limited. Some 400 homes took on water Sunday, and 16 University of Iowa buildings sustained some flood damage over the weekend. But the town's levees were holding and the Iowa River was falling.

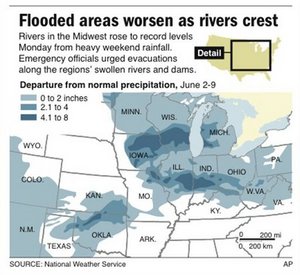

In northeast Missouri communities along the Mississippi, armies of Mennonites and Amish worked sandbag lines with convicted felons, college students and other volunteers in a race to beat the rising river. The very wide Mississippi was forecast to crest in the area by mid- to late-week.

"Today is our critical day, we need to get it done," said Monica Heaton, spokeswoman for Canton's emergency operations center.

In La Grange, Mo., a town of 1,000 people without a levee, City Hall was evacauted and about 50 residents left their homes Monday after Main Street and 20 homes flooded, City Administrator Mark Campbell said. The tiny town of Alexandria, just south of the Iowa border, abandoned sandbagging efforts and was completing an evacuation Monday.

|

| ©AP Photo/Sue Ogrocki |

| From left, Logan Lanz, Troy Massner, Dave Lanz and Jerry Edle bring a propane tank in from a flooded Iowa cornfield in Oakville, Iowa, Monday, June 16, 2008. |

In Cedar Rapids, hazardous conditions forced officials on Monday to stop taking residents into homes where the water had receded. Broken gas lines, sink holes and structural problems with homes made conditions unsafe, said Dave Koch, a city spokesman.

Frustrations spilled over at one checkpoint, where a man was arrested at gunpoint after he tried to drive past police in his pickup truck.

Warnings about the dangers of walking in the polluted water prompted hundreds of people to line up at a downtown clinic Sunday for free tetanus shots.

Teresa Schirm wore latex gloves and shorts as she stood ankle-deep in smelly brown water in her garage in Cedar Rapids.

|

| ©Associated Press |

In downtown Cedar Rapids on Monday, all manner of refuse could be seen floating down the Iowa River - 55-gallon drums labeled "corrosive," propane tanks, wooden fences and railroad ties. Dead birds and fish sat on the city's 1st Avenue Bridge.

A few blocks away, a paint store stood with its windows blown out. A line indicating the high-water mark could be seen about eight feet above the floor. At the gas station next door, strong currents had knocked over two pumps.

Also mixed into the floodwaters are pesticides, herbicides and fertilizer from Iowa's vast stretches of farmland.

Ken Sharp, environmental health director for the Iowa Department of Public Health, acknowledged that the floodwaters had the potential to make people sick. But he said the sheer volume of water can dilute hazardous substances.

"We don't typically see mass cases of disease or illness coming from floodwater, but under any circumstance like this, we want people to avoid it because we don't know what's in there."

In the aftermath, Sharp said, one of the biggest concerns will be preventing injuries from slipping or sliding, or from people stumbling into obstacles such as manholes with covers that have washed away.

|

| ©Associated Press |

"For rural folks, it's going to be hard to know if their water's safe or not," he said.

Adding to the misery were mosquitoes, which can breed rapidly in the standing water.

Greg Burg, assistant director of undergraduate biology at the University of Kansas, said the flooding "adds that much more water where they could potentially lay eggs and have the eggs survive."

Business was already heating up at Mosquito Control, a company in Rolfe, Iowa, that sprays insecticide from a crop-duster airplane.

"We are already getting several calls that mosquitoes that have finally hatched," said co-owner Rich Welter. "We're hearing from folks around Cedar Rapids and all around the northern half of Iowa."

When the waters rose Sunday in Oakville, a town of 400, Bob Lanz and his family tried to move their pigs out of harm's way. But they could only save a few. Most of their 350 sows and their 800 piglets were lost.

The family ripped out canvas ventilation curtains in the barn so the pigs "could at least have a chance," said Logan Lanz, Bob Lanz' grandson. "They were screaming. They were on top of each other. We had some big sows in there. They're frantic, and they run you over."

He said the water was choked with dead piglets.

On Monday, the Lanzes used their boat to retrieve two 1,000-gallon propane tanks that had floated up from one of their hog farms. They dragged the tanks to the top of a levee to get them onto dry land.

Treetops poked through the water, along with the aluminum roofs of their hog barns, glinting in the midday sun. The water rose to the eaves of the businesses on the main street.

Near Iowa City, Angela Betts and her three children were among those who fled last week when the Iowa River burst through a levee at Coralville. She stayed just long enough to fill two trash bags with clothes.

The family is now living in a shelter, and as far as Betts is concerned, everything she left behind can stay there.

"It bothers me, with everything that's in the water," Betts said. "I probably won't keep anything. It won't be worth it."

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter