WASHINGTON - A chunk of Antarctic ice about seven times the size of Manhattan suddenly collapsed, putting an even greater portion of glacial ice at risk, scientists said Tuesday.

|

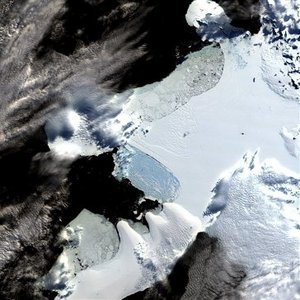

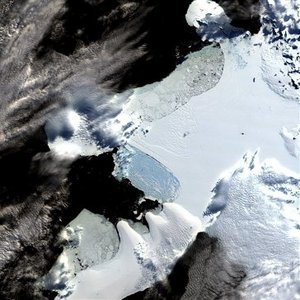

| ©AP Photo/ National Snow and Ice Data Center, NASA

|

| This satellite photo released by the National Snow and Ice Data Center at the University of Colorado at Boulder shows the Wilkins Ice Shelf on March 6, 2008 on the Southwest Antarctic Peninsula as it began to break apart.

|

Satellite images show the runaway disintegration of a 160-square-mile chunk in western Antarctica, which started Feb. 28. It was the edge of the Wilkins ice shelf and has been there for hundreds, maybe 1,500 years.

This is the result of global warming, said British Antarctic Survey scientist David Vaughan.

Because scientists noticed satellite images within hours, they diverted satellite cameras and even flew an airplane over the ongoing collapse for rare pictures and video.

"It's an event we don't get to see very often," said Ted Scambos, lead scientist at the National Snow and Ice Data Center in Boulder, Colo. "The cracks fill with water and slice off and topple... That gets to be a runaway situation."

While icebergs naturally break away from the mainland, collapses like this are unusual but are happening more frequently in recent decades, Vaughan said. The collapse is similar to what happens to hardened glass when it is smashed with a hammer, he said.

The rest of the Wilkins ice shelf, which is about the size of Connecticut, is holding on by a narrow beam of thin ice. Scientists worry that it too may collapse. Larger, more dramatic ice collapses occurred in 2002 and 1995.

Vaughan had predicted the Wilkins shelf would collapse about 15 years from now. The part that recently gave way makes up about 4 percent of the overall shelf, but it's an important part that can trigger further collapse.

There's still a chance the rest of the ice shelf will survive until next year because this is the end of the Antarctic summer and colder weather is setting in, Vaughan said.

Scientists said they are not concerned about a rise in sea level from the latest event, but say it's a sign of worsening global warming.

Such occurrences are "more indicative of a tipping point or trigger in the climate system," said Sarah Das, a scientist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute.

"These are things that are not re-forming," Das said. "So once they're gone, they're gone."

Climate in Antarctica is complicated and more isolated from the rest of the world.

Much of the continent is not warming and some parts are even cooling, Vaughan said. However, the western peninsula, which includes the Wilkins ice shelf, juts out into the ocean and is warming. This is the part of the continent where scientists are most concern about ice-melt triggering sea level rise.

"This is the result of global warming, said British Antarctic Survey scientist David Vaughan."

but then:

Much of the continent is not warming and some parts are even cooling, Vaughan said.

So is that also a result of global warming or is that a result of global cooling.

I am just curious why he states that the first part is a result of global warming, but then in the next breath says that most of the continent is not warming, but even cooling in parts without coming out with a blanket statement why that is.

Is there an obvious explanation for this?