The study, authored by Matthias Toplak and Lukas Kerk and published in the journal Current Swedish Archaeology, investigates archaeological findings from Gotland, where half of all documented cases of male teeth filing have been discovered. Alongside the intriguing possibility of Viking tattoos, these practices represent the known forms of body modification taking place in early medieval Scandinavia.

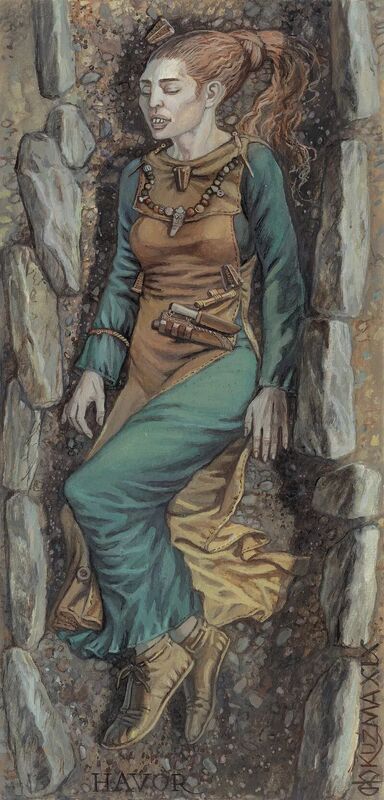

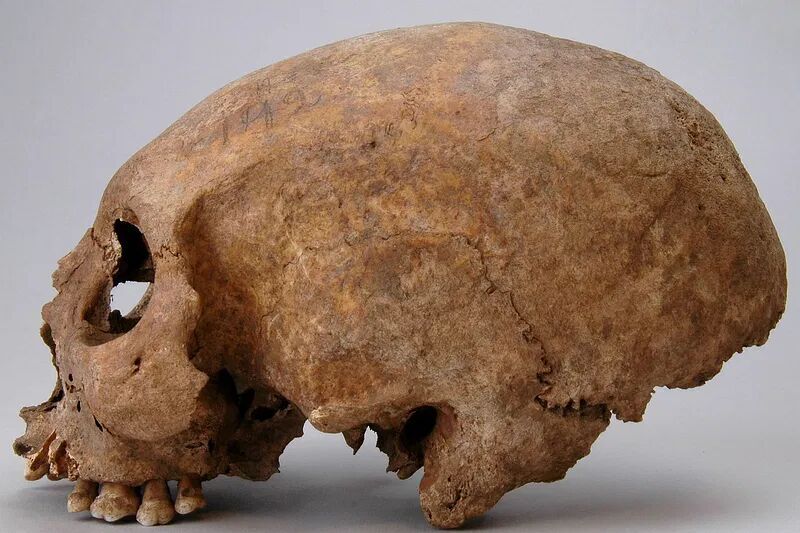

Dating back to the latter part of the eleventh century, all three women were interred in different locations across Gotland. Their skull modifications bestowed upon them a distinctive and remarkable appearance, elongating their heads. Further details are discerned in two of the cases: one woman passed away between the ages of 25 and 30, while the other was between 55 and 60 years old. The drawing below, based on excavation reports, is an artistic rendering of how this older woman would have looked when she was buried.

The methodology behind their skull elongation remains a subject of intrigue. This practice, observed across various ancient and medieval cultures spanning the South Americas, Central Asia, and Southeast Europe, involves binding young children's heads with wood or cloth, typically under the age of three. In Europe, such modifications predominantly occurred among females.

The authors believe that the practice came to Scandinavia from southeast Europe - it could be found in Bulgaria from the 9th to 11th centuries. "It remains unclear how the custom of skull modification reached Gotland," they write."Either the three females from Havor, Ire and Kvie were born in south-eastern Europe, perhaps as children of Gotlandic or East Baltic traders, and their skulls were modified there in the first years of life. Or the modifications were made on Gotland or in the eastern Baltic, respectively, and thus represent a cultural adoption long unknown to the Scandinavian Viking Age. A common background of the three females can be assumed due to the close chronological dating of the three burials, and especially due to the very similar execution of the skull modifications."

There is still much to understand about these three women. Did the local community consider them different or outsiders, or were they given special status because of their appearance? The authors tell Medievalists.net:

We assume that these three females were indeed exposed characters in their society even though we are not quite sure if they were actually regarded as outsiders. According to the aDNA-analysis, at least one of these females might come from Gotland. But we are very sure that they had a special significance as they were signalling a different identity and mediating certain narratives (e.g. of far-reaching contacts and exotic cultural influences). And, according to their burials, this special significance was regarded as something positive as at least the female individual from Havor was buried not only with the Gotlandic 'standard' dress attire but she was overequipped with typical Gotlandic jewellery.The authors also found similarities with another type of body modification done in the Viking Age: the filing of teeth. Researchers began noticing this practice in 1989 and we currently have about 130 cases of males who had their teeth modified in the form of single horizontal filed grooves. All the cases involved men who were at least 20 years old, which would indicate that unlike for the three women, these modifications were both voluntary and desired. Several theories exist on why they took part in this - perhaps as a test to endure pain or to show membership in a warrior group. You can read more about Vikings and their Filed Teeth.

Furthermore, the study underscores the dynamic nature of these embodied signals, suggesting that the meanings behind these body modifications could evolve and be reinterpreted over time. The researchers argue that these physical alterations were part of a broader system of communication within Viking Age society, where individuals could express aspects of their identity, status, and affiliations through their bodies. By decoding these embodied signals, researchers can gain valuable insights into the social dynamics and cultural practices of Viking communities, revealing a deeper understanding of how individuals navigated and communicated their place within their society through physical transformations.

The article, "Body Modification on Viking Age Gotland: Filed Teeth and Artificially Modified Skulls as Embodiment of Social Identities," by Matthias S. Toplak and Lukas Kerk, appears in the latest issue of Current Swedish Archaeology. Click here to read it.

Matthias S. Toplak is the Head of the Viking Museum Hedeby. You can read more of Matthias' research through his Academia.edu page.

Lukas Kerk is a Doctoral student at the University of Munster, where his research focuses on 'Archaeologically evident permanent body modifications'. Click here to visit his university webpage.

Comment: It's notable that evidence of cranial deformation, as well as natural, unusually shaped, skulls - that, one would assume, are what people were were attempting to imitate - have been found in sites that date as far back as 10,000 years ago, and across much of the planet: