The Great Barrier Reef, Australia

Coral at the Great Barrier Reef (GBR) faces another year of exile from the climate scare headlines with news that the record levels reported in 2021-22 have been sustained in the latest annual period to May 2023. A small drop in the three main areas of the reef was well within margin of error territory, with the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS) reporting that regional average hard coral cover in 2022-2023 was similar to last year at 35.7%. Most reefs underwent

little change during the year.

Coral at the reef has been bouncing back sharply for a number of years, with a record 36-year high reported in 2022. But the news of this spectacular recovery has been largely ignored in most media since it had previously been a go-to poster scare story for collectivist Net Zero promoters. But connecting the fate of tropical corals to global warming was always a difficult ask since they grow in waters between 24-32°C. Short boosts in local temperatures can cause temporary bleaching, but it is scientifically impossible to pin it on human-caused climate change, although pseudoscientific 'attribution' computer models try very hard.

In the latest year, there was a short local temperature rise, but little bleaching was reported during the 2023 summer. No cyclones hit the reef and crown-of thorns starfish attacks were limited. Nevertheless, natural stresses will always affect the eco-system and AIMS states that these paused the growth of hard coral on some of the reefs.

Fauna in the Great Barrier Reef

Like most

state-funded scientific bodies,

AIMS is fully signed up to climate extremism and delivering politically correct messages to promote the Net Zero solution. Despite reporting what is now a substantial multi-year recovery, it notes that the future is predicted to bring more frequent, intense and enduring marine heatwaves, alongside the persistent threat of crown-of thorns starfish outbreaks and tropical cyclones. More frequent mass coral bleaching is a sign that the GBR is experiencing the consequences of climate change, it claims. However, in a different part of its latest report, AIMS accepts that the recent substantial recovery occurred despite two mass coral bleaching events in 2020 and 2022. There is an acceptance that this underlines that "widespread coral bleaching does not necessarily lead to extensive coral mortality".

But pockets of extremist catastrophism remain in the mainstream media, notably in the

Guardian, fighting to keep the coral destruction story going. A year ago, the newspaper

reported that the GBR still had "some capacity" for recovery, but the window was closing fast as the climate continued to warm. Of course the

Guardian has form as long as your arm on this score. Back in 1999, George Monbiot

told its readers that the "imminent total destruction of the world's coral reefs is not a scare story but a fact".

In last year's

Guardian report, Dr. Mike Emslie, who leads the AIMS monitoring service, said he felt a "couple of bullets" had been recently dodged. While the recovery is great, "the predictions are the disturbances will get worse", he suggested. "The naysayers can put their heads in the sand all they like, but the frequency of disturbances is going gangbusters," he claimed. Dr. David Wachenfeld from the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority claimed "global heating" of 1.5°C is considered a "guardrail for reefs", after which the bleaching comes along too quickly for strong recovery.

Coral reefs have been around in one form or another for hundreds of millions of years. Current global temperatures are towards the lower end of the paleoclimatic record. One might wonder how corals manage to survive temperatures up to 10°C higher in the past?Back in the real world, we can see how the recent solid recovery was sustained across the three main areas of the GBR.

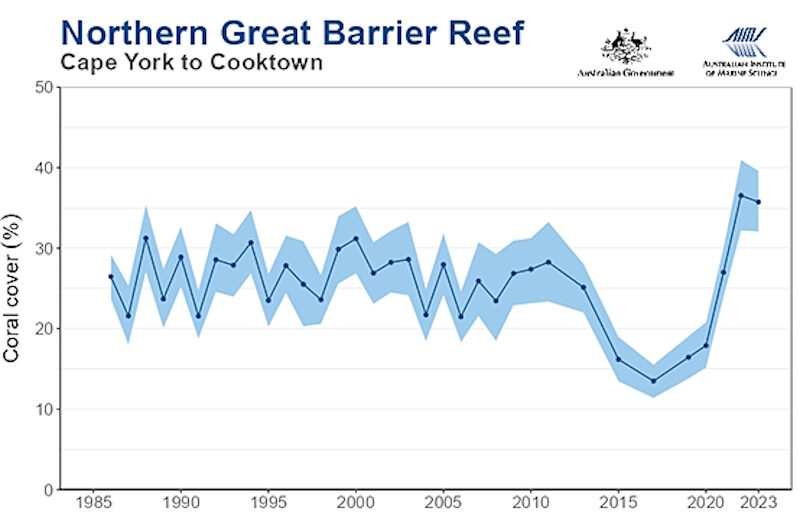

© Australian Institute of Marine Science

The recovery in the northern GBR actually started around 2017. Last year the coral declined slightly from 36.5% to 35.7%, and was easily within the margin of error calculated by the AIMS. Typhoon Tiffany passed through at the end of the previous reporting season, and could have been responsible for some loss.

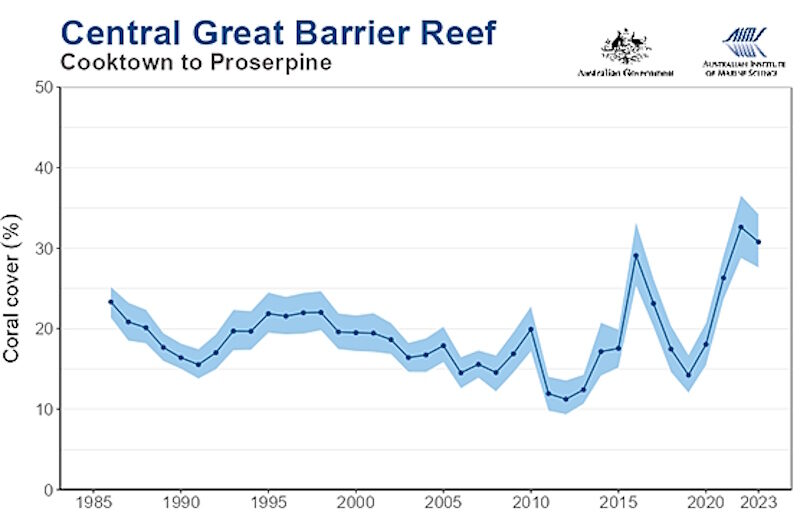

© Australian Institute of Marine Science

In the centre of the reef, the strong recovery of hard coral cover to 32.6% last year eased slightly, but again, as the AIMS noted, it was within the margin of error.

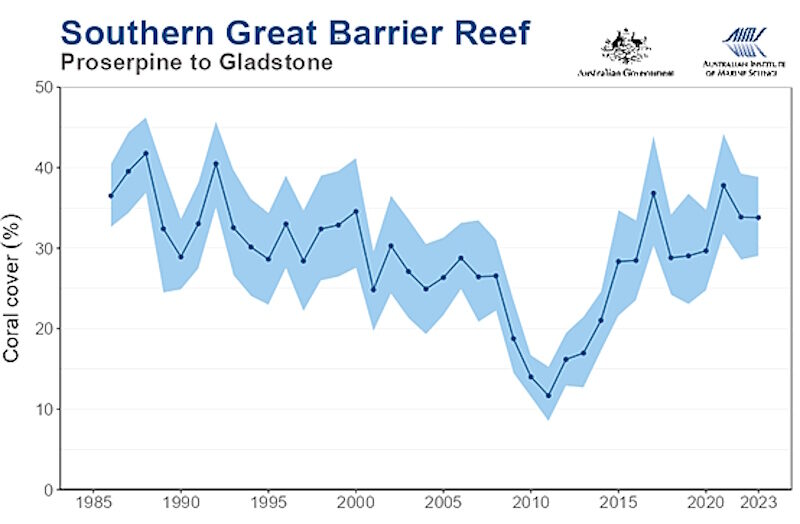

© Australian Institute of Marine Science

The southern end of the GBR has generally had higher coral cover than elsewhere, but has shown greater variability over the observed record. Last year's cover was 33.8%, compared with 33.9% the year before. Some coral was reported to have been lost due to starfish predations.

The GBR is the largest reef system on Earth and runs for over 1,400 miles down the eastern side of Australia. It is also the most surveyed reef in the world and the results of scientific endeavour are widely distributed. While this work is often politicised, it is clear that recent evidence shows that temporary spikes in temperature, which occur naturally in the oceans, can cause bleaching.

However, this bleaching process can rapidly go into reverse when local conditions stabilise. These findings have been confirmed elsewhere, notably in the remote Palmyra Atoll, 1,200 kms south of Hawaii. A

10-year survey recently observed sudden changes in temperature up to 3°C on two occasions, leading to substantial damage to the coral. A 2015-16 spike led to 90% of the coral bleaching, but the researchers found that within a year only 10% of the coral had died. Within two years, the corals had returned to pre-bleached levels.

The researchers concluded that the coral structures "show evidence of long-term stability" - but don't hold that front page.

Chris Morrison is the Daily Sceptic's Environment Editor

Yet another stab in the eye of nonsense that the Global warming brigade are so known for.