That is illustrative of where the story goes from there — a performance relevant to the humor enjoyed in Britain today, and one which colors the high Middle Ages as a time of artistic liberty, social mobility, and vigorous nightlife.

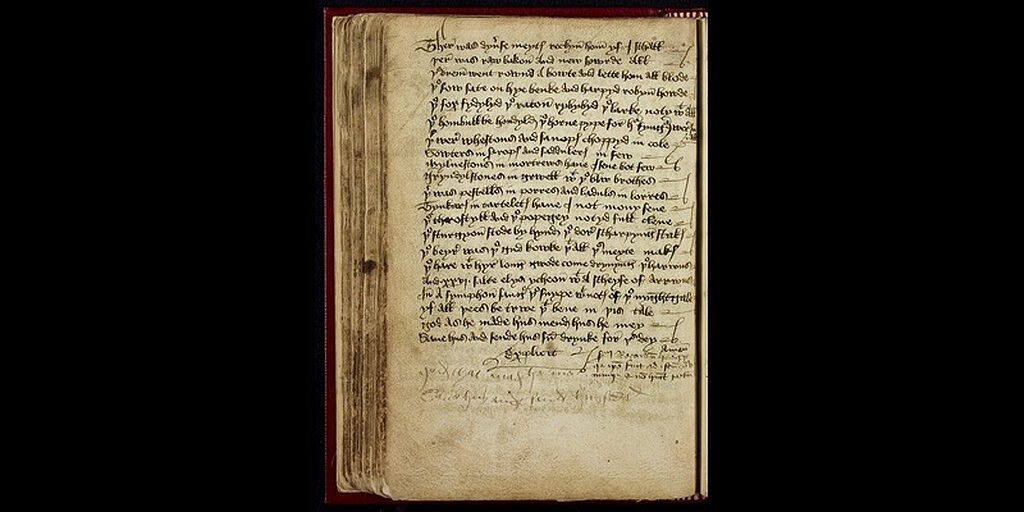

Heege's booklet contains three texts gleaned from the jester's material: a Hunting of the Hare story featuring a killer rabbit, a mock sermon in prose in which three kings eat so much that 24 bulls explode out of their stomachs and begin sword fighting, and an alliteration nonsense verse entitled The Battle of Brackonwet.

Reminiscent of Geoffrey Chaucer's writings, or Monty Python's killer rabbit of Caerbannog sketch in their film Monty Python and The Holy Grail, The Hunting of the Hare is a rhyming burlesque romance, meaning the frivolous is important and the serious is treated lightly.

In it, two fictional peasants get involved with a series of hijinks that includes a cany coney who kicks one of them in the head.

In The Battle of Brackonwet, Robin Hood, killer bumblebees, and jousting bears color a tale full of nonsense within what would have been Mr. Heege and the minstrel's local neighborhood on the border of Derbyshire and Nottinghamshire where Mr. Heege lived.

The texts were found in the National Library of Scotland by Dr. James Wade, of Cambridge's English Faculty, who recently wrote a paper on them explaining that such material is extremely rare, but offers a wondrous glimpse into life not only among England's medieval middle-class, but the skill and appreciation for minstrels.

"Here we have a self-made entertainer with very little education creating really original, ironic material. To get an insight into someone like that from this period is incredibly rare and exciting," Dr. Wade said.

"You can find echoes of this minstrel's humor in [today's] shows like Mock the Week, situational comedies, and slapstick. The self-irony and making audiences the butt of the joke are still very characteristic of British stand-up comedy."

During the Middle Ages minstrels roamed between fairs, taverns, and baronial halls to entertain with songs and stories either across the country or along a local circuit. Many had day jobs, such as a plowman or peddler, but gigged through the nights and weekends.

"These texts remind us that festive entertainment was flourishing at a time of growing social mobility," said Dr. Wade. "[They] give us a snapshot of medieval life being lived well."

"People back then partied a lot more than we do today, so minstrels had plenty of opportunities to perform. They were really important figures in people's lives right across the social hierarchy."

It also shows that what we sometimes think of as a society of science-denying religious tyranny created not only these talented comics but people who enjoyed their work enough to copy it down.

Mr. Heege worked for a noble family and would have been considered right and proper, yet he appears to have had a sense of humor and to have enjoyed literature that others may have dismissed as too lowbrow to preserve.

What else can we conclude when the man committed the minstrel's rhymes of "Drink you to me and I to you and hold your cup up high — God loves neither horse nor mare, but merry men that in the cup can stare" to memory well enough to write it down?

Reader Comments

So it is my understanding that these academics can't get their heads around how an uneducated dweeb like all uneducated dweebs could possibly come up with their on cue, witty theatre. They see everyone in the middle ages who were not exposed to an education as incapable to wielding intelligence when in fact, all humans are highly intelligent and always have been throughout all the ages. They see those of us, their contemporaries who have not attended Oxford et al. as a lower form of humanity, one that is bereft of any intelligence. The article above disgusts me.