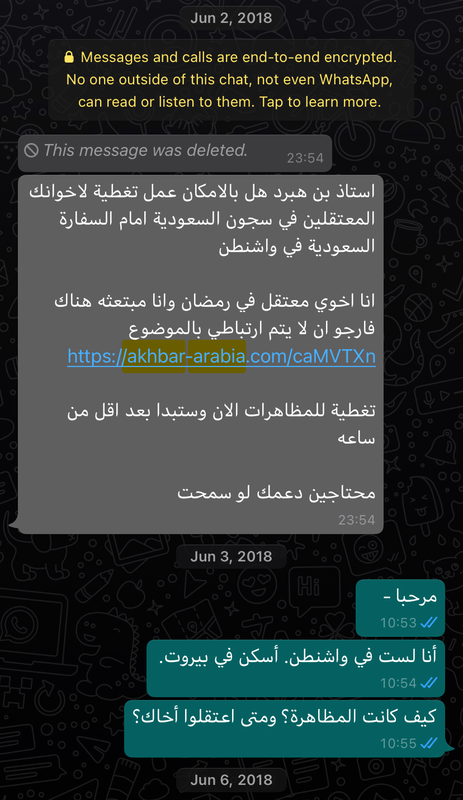

Hubbard, a reporter covering the Middle East, wrote on Sunday that a hacking attempt was first made on his phone in 2018, when he received a "suspicious" Arabic language text message inviting him to a protest outside the Saudi embassy in Washington, DC. A similar message followed, and digital rights group CitizenLab told Hubbard both messages originated from servers that had previously been used to target Saudi activists.

Two more attempts followed in 2020 and 2021, but they were so-called 'zero-click' exploits, meaning Hubbard would not have had to click on any links or messages to allow the hackers into his phone. These attempts were successful, and once inside Hubbard's smartphone, the hackers were able to view all its contents, surreptitiously activate his microphone and camera, and delete traces of their previous hacks.

CitizenLab's researchers told Hubbard the hackers likely used 'Pegasus' malware all four times. Pegasus is a sophisticated hacking tool developed by an Israeli firm, NSO Group, and sold to state-level clients around the world. Human rights activists detected its clients in Saudi Arabia, Hungary, India, the United Arab Emirates (UAE) and many other countries. Rival politicians, foreign governments, journalists, activists, and legal and business figures were reported among the targets. Dubai's Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum used the malware to hack his ex-wife's phone, the Moroccan government reportedly used it to spy on French President Emmanuel Macron, and Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban's administration is accused of deploying the malware against the Hungarian media.

NSO Group denied that its software was used to hack Hubbard's phone. The Israeli firm said it did not possess the technology to do so back in 2018, and that Saudi officials could not have hacked the reporter in 2020 and 2021 because of unspecified "technical and contractual reasons and restrictions."

Saudi Arabia's use of NSO Group's malware was canceled by the company in 2018 following the murder of anti-government journalist Jamal Khashoggi, but NSO resumed business with the Kingdom the following year, adding some restrictions to Riyadh's use of the hacking software, The Times reported. Earlier this year, NSO Group said its "technology was not associated in any way with the heinous murder" of Khashoggi and was not used to "listen, monitor, track, or collect information regarding him or his family members."

The Saudi embassy in Washington declined to comment on Hubbard's article. Previously, Riyadh denied having used Pegasus to monitor phone calls. However, there have been several reports detailing how the Kingdom used the software to target journalists.

According to CitizenLab, three dozen journalists with the Qatari-funded Al Jazeera news network had their phones hacked last year by Saudi intelligence.

Amid a global outcry over the use of its products, NSO Group has alternated between downplaying its number of customers and their targets, while insisting that its products are designed for use in legitimate law enforcement investigations, and claiming that it severed multiple business relationships over alleged human rights abuses.

The company now says it wants to help regulate the very surveillance software it got rich selling. In a letter to the United Nations dated September 30, the Israeli firm offered to be a "constructive participant" in building an "international legal framework" to regulate government and private phone snooping.

Comment: