So much for having a "strong safety profile," as Dr. Scott Gottlieb claimed in an interview on the day Merck first publicized the research.

It's perfectly understandable why Merck might choose to play down this safety risk: assuming it's approved, the drug is widely expected to be one of "the most lucrative drugs ever" - which is one reason why Merck's shares soared into double-digit territory after the announcement.

As we reported earlier this week, Merck and its "partner" Ridgeback Biotherapeutics will profit immensely by charging customers up to 40x what it costs to make the drug, which Ridgeback originally licensed from Emory University for an "undisclosed sum". The drug was developed with funding from the federal government.

According to Barron's, some scientists who have studied the drug believe that its method of suppressing the virus could potentially run amok within the body.

Some scientists who have studied the drug warn, however, that the method it uses to kill the virus that causes Covid-19 carries potential dangers that could limit the drug's usefulness.In particular, Raymond Schinazi, a professor of pediatrics and the director of biochemical pharmacology at Emory who studied the drug while it was being developed, and published a number of papers on NHC, the compound that's the active ingredient in the drug. He published a paper that showed the drug can produce a reaction like the one described above, and insisted it shouldn't be given to young people - especially pregnant women - without more data.

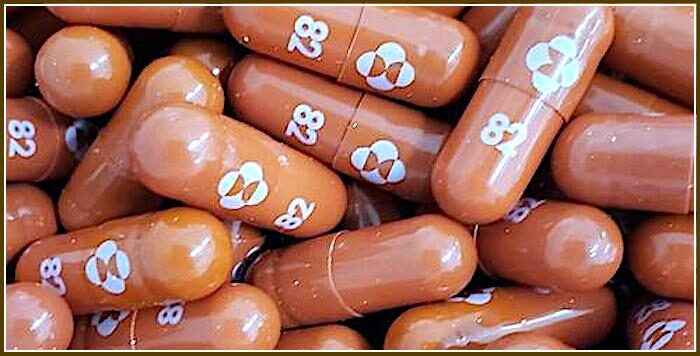

Molnupiravir works by incorporating itself into the genetic material of the virus, and then causing a huge number of mutations as the virus replicates, effectively killing it. In some lab tests, the drug has also shown the ability to integrate into the genetic material of mammalian cells, causing mutations as those cells replicate.

If that were to happen in the cells of a patient being treated with molnupiravir, it could theoretically lead to cancer or birth defects.

Schinazi told Barron's that he did not believe that molnupiravir should be given to pregnant women, or to young people of reproductive age, until more data is available. Merck's trials of molnupiravir have excluded pregnant women; the scientists running the trial asked male participants to "abstain from heterosexual intercourse" while taking the drug, according to the federal government website that tracks clinical trials.Barron's even shared a paper published in the Journal of Infectious Diseases in May by Schinazi and scientists at the University of North Carolina which reported that NHC can cause mutations in animal cell cultures in a lab test designed to detect such mutations - something Merck claims it has tested for. The paper's authors concluded that the risks for molnupiravir "may not be zero".

Merck told Barron's that it has run "extensive tests" on animals which it says show that this shouldn't be an issue. A Merck spokesman said:

"The totality of the data from these studies indicates that molnupiravir is not mutagenic or genotoxic in in-vivo mammalian systems."Still, scientists and doctors who have studied NHC say that Merck needs to "be careful," and it's not just Schinazi warning about the drug's potential risks.

Dr. Shuntai Zhou, a scientist at the Swanstrom Lab at UNC, said he is certain that the drug will integrate itself into the DNA of mammalian hosts.

"There is a concern that this will cause long-term mutation effects, even cancer. Biochemistry won't lie. This drug will be incorporated in the DNA."Merck hasn't yet released any data from its animal studies, but the scientists believe that it would take long-term studies to show that the drug is truly totally safe.

"Proceed with caution and at your own peril," wrote Raymond Schinazi in an email to Barron's.

Analysts are already warning that these questions about the drug's safety suggest the reaction in Merck's shares was a little "overblown", to say the least. Investors apparently were so eager for a new "pandemic panacea" (now that the mRNA jabs have proven to be much less effective than advertised) that they didn't ask too many questions about safety, or even question the paucity of data. One analyst for SVB Leerink Dr. Geoffrey Porges described investors' reaction from Friday as "wishful thinking".

Even once the FDA authorizes the drug, Dr. Porges believes it will come with strict limitations on who can and can't use it. "I think it is effectively going to be a controlled substance", Dr. Porges said, adding that the risks to pregnant women, or women who may soon become pregnant, could present thorny problems for the FDA's advisory committee reviewing the drug.

Given that the safety risks of the drug seem well-documented already, Wall Street's gushing about the drug's prospects - "it really is THAT good", one analyst insisted - seems like an idiotic blunder in retrospect. The product of what one might call "magical thinking".

Comment: This is just one more quick fix money-maker where-in profits would cover/cover-up any potential lawsuits.