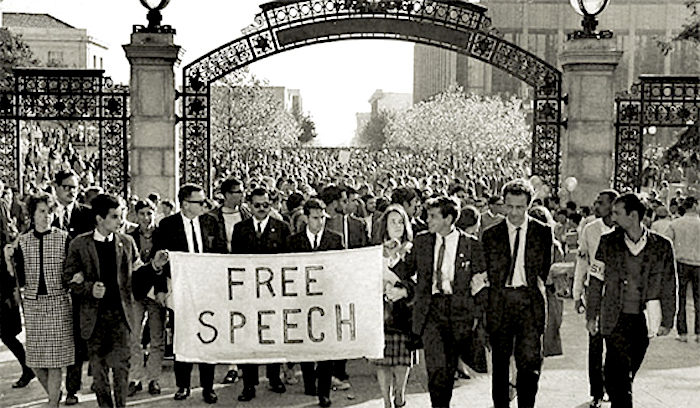

At a recent conference, I talked to a young college graduate who dabbles in journalism and he said, rather offhandedly, "There's always good attention paid to stories about free speech on campus." This produced a hearty laugh from me, because the overwhelming interest in campus-speech issues is a recent development.

Indeed, over my first ten years at the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (2001-11), we begged people to pay attention to the fact that it was shockingly easy to get in trouble for what you said on campus. It is real progress that now when I bring up free speech on campus, very few people ever say, "I didn't realize it was an issue." Yet even though the issue is more prominent in public conversation than it's ever been since the emergence of "political correctness" in the late '80s and early '90s, whenever I talk to conservatives, there is often a deep sense of pessimism about what can be done about campuses.

I understand why: The picture can seem quite bleak, particularly when it comes to viewpoint diversity. But given the notable progress that defenders of free speech both left and right have made on American campuses in recent years, the considerable distance we still have left to go, and the increased attention that can only help us traverse that distance, now is not the time to give in to defeatism.

Consider the major threats to free speech on campus that we at FIRE had on our radar as recently as 2011: The prevalence of campus speech codes, the Obama administration's wrongheaded federal regulations, and the refusal of much of the media, the general public, politicians, and even universities themselves to take threats to free speech on campus seriously.

On all three fronts we have made tremendous progress. The percentage of colleges that maintain severely restrictive speech policies declined from 74.2 percent in 2009 to 28.5 percent in 2018. The problematic Department of Education regulations that began appearing in 2011 have been repealed or revised in recent years. And the issue of free speech on campus has gone from one that struggled mightily for public attention to one that is publicly discussed everywhere, from mainstream-media outlets to state and federal legislatures to campuses themselves. University presidents and top university lawyers now discuss the issue openly and, while dozens of colleges across the country have adopted a new and strong commitment to freedom of speech, often based on the "Chicago Statement."

Still, the pessimism in some corners makes sense. Despite these welcome developments, there can be no denying that the problem seems worse than it did in, say, 2012, when the state of free speech on campus actually appeared to be improving. What changed? As I've discussed at length in countless interviews, and in my book with Jonathan Haidt, The Coddling of the American Mind, the present generation of students is no longer as reliably pro-free speech as students were prior to 2013-14. (It often comes as a surprise to conservatives that from 2001 to 2012, students were actually, in general, quite strong in backing free-speech protections.)

This change was real and conspicuous, and conservatives are right to be concerned by it. What's more, many campuses have still not taken basic, initial steps to protect free speech on campus, including:

- Ending their violations of the law. While, as I've mentioned, we've made great progress in cutting down the percentage of top colleges that maintain the most restrictive speech codes, there are still too many colleges that do, and many more that maintain less restrictive, though still unconstitutional, codes.

- Pre-committing and recommitting to the protection of free speech and inquiry. It's not enough to adopt a policy that protects free speech and academic freedom. University leaders should constantly look for ways to remind their communities of these values.

- Defending student and faculty rights loudly and early. When there is a speech controversy on campus, college leaders should make clear that nobody will be punished for unpopular or controversial speech and that a failure to protect such speech would contradict their institution's values.

- Teaching free speech from Day One. Most colleges don't introduce students to the principles of free speech, academic freedom, and truth-seeking in their orientation programs. These are values that are core to the mission and purpose of a college, and they should be taught starting the first day students arrive on campus.

- Collecting solid scholarly data on the problem. What is the state of free speech, dissent, and open inquiry on any given campus? Colleges should regularly survey students and faculty to find out.

It may not provide the visceral satisfaction of throwing up your hands to exclaim that the sky has fallen, but it will surely make a much bigger difference.

About the Author:

Greg Lukianoff is the president and CEO of the Foundation for Individual Rights in Education (FIRE), co-author of The coddling of the American Mind.

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter