Comment: In addition to flight, expulsion and dispossession, the Guardian should have added mass murder. The Jewish immigrants not only kicked the Palestinians off their land, they slaughtered entire villages. But that might bring the analogy to the Nazi slaughter of Jews too close to home.

In the heat of the recent controversy in Britain over Zionism and anti-semitism, relatively little attention was paid to the Palestinian side of this ever controversial story. Europe's Jews were the victims of racism, persecution and extermination on a massive and unprecedented scale during the Nazi era. Palestinians, in their turn, in a different way, were victims too.

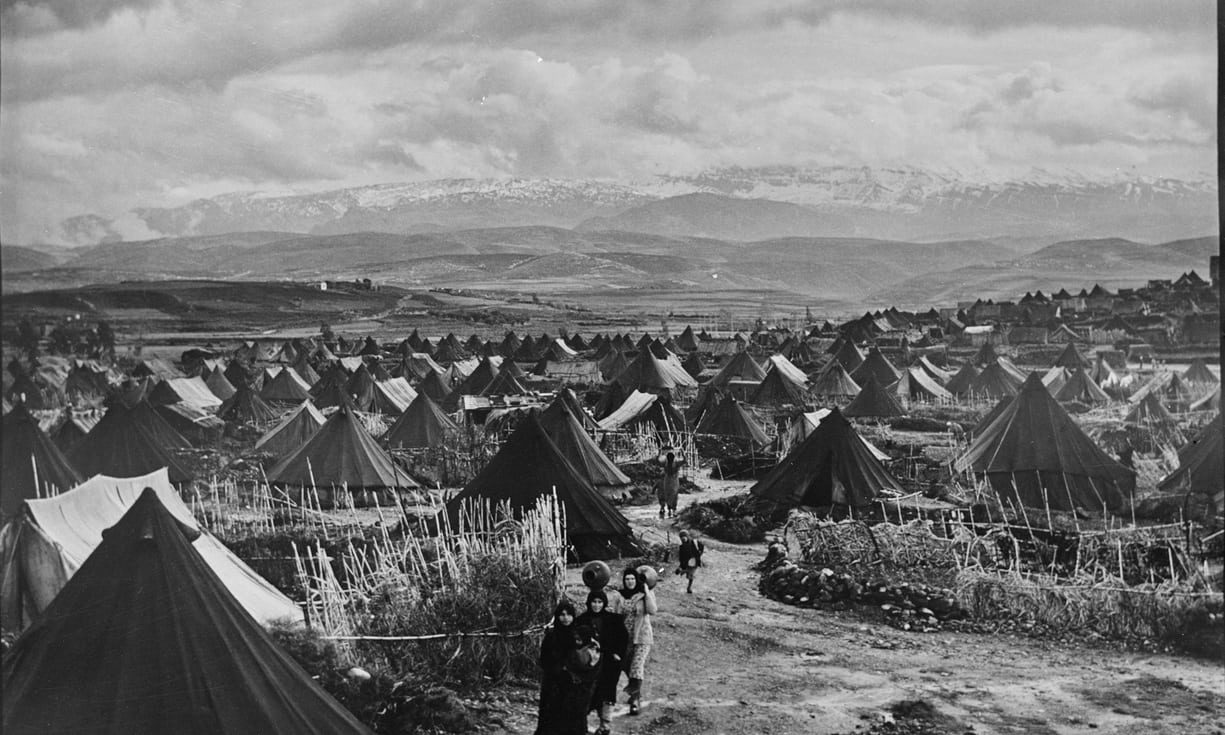

Salman Abu Sitta's autobiography is a vivid and angry reminder of that. It tells the story of just one of some 750,000 Palestinians who became refugees in the war that followed the UN decision to partition the country in 1947. When he was growing up near Beersheba in the final decade of the British mandate, Jews were first a distant then a closer and menacing presence, well-organised foreign immigrants with guns and detailed maps. Their motives and experiences were remote and unfamiliar.

Abu Sitta takes on board much of the "new history" largely written by Israelis who punctured the older myths of the war, emphasising the military superiority of Zionist forces and the weaknesses and rivalries on the Arab side. He also provides fascinating glimpses of the Palestinian fedayeen - "infiltrators" and "terrorists" to the Israelis - who crossed the border after 1948 not only to "defeat the invader" but to visit abandoned homes and fields on which new settlements were being built.

Uprooted to Gaza, the Gulf and far beyond, he trained as an engineer and spent decades tracking down maps to document his lost homeland. In Cairo and Kuwait he met the "indefatigable" Yasser Arafat and others who formed the Palestinian liberation movement, Fatah, and the PLO, some later assassinated by the Israelis. "We all believed in armed resistance as the route to recovering our homes," he writes. Abu Sitta humanises a story which has been largely told from the Israeli side.

His book is a forceful re-statement of the Palestinian conviction that Zionism is illegitimate, from the Balfour Declaration of 1917 to the present day. Compromise is treachery, as in 1974 when the PLO first began to make "calamitous concessions" that held out the hope of a two-state solution as originally envisaged by the UN - and seemed for a while to be within reach after the first intifada. The Oslo agreement in 1993, offering self-rule but in fact leading to the expansion of settlements in the post-1967 territories, is portrayed as fatal error that was supported by an exhausted Arafat in the name of "realism."

In 1995 Abu Sitta, armed with a foreign passport, returned to the land of his birth to see his family's estate occupied by kibbutzim that had been founded by Jews hailing from Russia, Ukraine, Germany and South Africa. But by then the "faceless enemies" he remembered as a 10-year-old child had been transformed into Israelis with their own language, culture, memories and psychology. Palestinians were not part of their world.

Now, nearly 70 years since the Nakba, 70% of Israelis were born and raised in a country whose landscape has been transformed almost beyond recognition, most of its Arab character deliberately erased. Alongside that, Abu Sitta's calculation that the majority of Palestinian refugees live only a few miles from their places of origin in 1948 - and could thus go home again - looks like a case of so near yet so far.

Even amidst intensifying talk of the death of the two-state solution, the idea that those aged refugees and millions of their descendants will be be able to exercise their "right of return" to what is now Israel looks like a forlorn hope. Abu Sitta's memoir conveys a still burning sense of outrage at the injustice of the dispossession of the Palestinians and the denial of their rights - a personal and collective Nakba without end. But it offers scant hope for a better future for two peoples suffering - albeit unequally - under the burden of their intertwined history.

Mapping my Return: A Palestinian Memoir, by Salman Abu Sitta

Reader Comments