© Bénédicte Muller

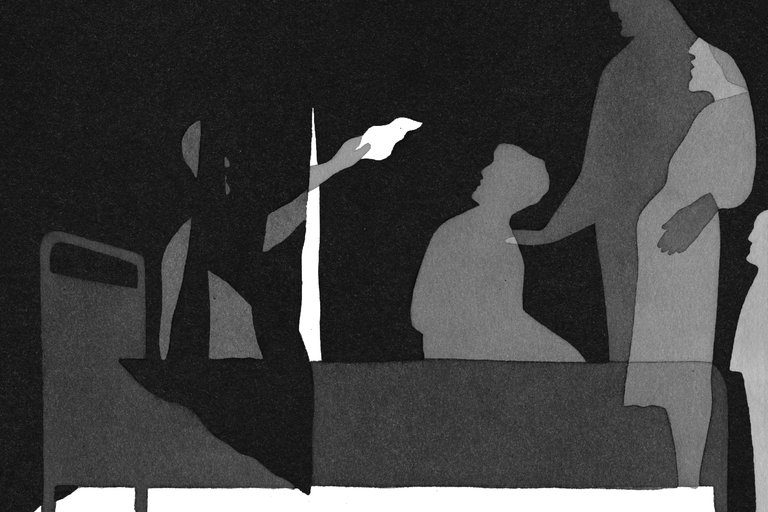

The patient's hair was styled with curls so stiff, they held her head a few inches up from her hospital pillow. She had painted her lips a shade of bright pink that exuded the confidence of age.

Just after her colon burst, she was still awake. She looked around, at me, at the monitors. She asked for pain medication. "Am I dying?" she asked.

"We think so," I said, touching her manicured fingernails. "I am here with you."

Later, she kept her eyes closed but opened them when we talked. It was a state that the author and hospice nurse Barbara Karnes described as "one foot in each world."

"Can I do anything?" I asked.

"No, honey. I'm just tired." She closed her eyes again.

Still later, she lapsed into a stupor. It was as if I wasn't in the room at all, as if she'd gotten so close to death that she could no longer see the living world. With each hour, her lipstick appeared brighter as if in defiance as her blood pressure dropped and her skin whitened. Midmorning, she died.

While some of the symptoms of dying, like

the death rattle, air hunger and terminal agitation, can cause alarm in witnesses, other symptoms are more gentle.

The human body's most compassionate gift is the interdependence of its parts. As organs in the torso fail, the brain likewise shuts down. With the exception of the minority of people who suffer sudden death, the vast majority of us experience a slumberous slippage from life. We may be able to sense people at the bedside on a spiritual level, but we are not fully awake in the moments, and often hours, before we die.

Every major organ in the body - heart, lungs, liver, kidneys - has the capacity to shut off the brain. It's a biological veto system.

When the heart stops pumping, blood pressure drops throughout the body. Like electricity on a city block, service goes out everywhere, including the brain.

When the liver or kidneys fail, toxic electrolytes and metabolites build up in the body and cloud awareness.

Failing lungs decrease oxygen and increase carbon dioxide in the blood, both of which slow cognitive function.

The mysterious exception is "terminal lucidity," a term coined by the biologist Michael Nahm in 2009 to describe the brief state of clarity and energy that sometimes precedes death. Alexander Batthyány, another contemporary expert on dying, calls it "the light before the end of the tunnel."

A 5-year-old boy in a coma for three weeks suddenly regains consciousness. He thanks his family for letting him go and tells them he'll be dying soon. The next day, he does.

A

26-year-old woman with severe mental disabilities hasn't spoken a word for years. Suddenly, she sings, "Where does the soul find its home, its peace? Peace, peace, heavenly peace!" The year is 1922. She sings for half an hour and then she passes away. The episode is witnessed by two prominent physicians and later recounted by them separately, at least five times, with identical descriptions.

Early reports of terminal lucidity date back to Hippocrates, Plutarch and Galen. Dr. Nahm

collected 83 accounts of terminal lucidity written over 250 years, most of which were witnessed by medical professionals. Nearly 90 percent of cases happened within a week of death and almost half occurred on the final day of life.

Terminal lucidity occurred irrespective of ailment, in patients with tumors, strokes, dementia and psychiatric disorders. Dr. Nahm suggested the mechanism of terminal lucidity may differ from one disease to another. For example, severe weight loss in patients with brain tumors could cause the brain to shrink, yielding fleeting relief of pressure on the brain that might allow for clearer thinking. Yet this theory doesn't explain terminal lucidity in people dying from dementia, kidney failure or other diseases. Like death itself, terminal lucidity retains a screen of mystery.

My grandfather talked to us for 10 minutes the day before he died. He hadn't spoken coherently in days. His hands had become baby-like, grasping our fingers or the bed railing reflexively. The weight of his eyelids had become too heavy to lift.

Suddenly, he was back. "What's the good word?" he asked, as if that day was the same as all the days before. He marched down the line of grandchildren at his bedside, asking for the latest news in our lives. He asked if they ever finished building the Waldorf Astoria in Jerusalem. He made a joke, one I can't remember except for the way he smiled out of the right side of his mouth, tilted his head from side to side, and held up his hands in jest.

And then, again, he was gone.

Comment: