But new research shows that the extinct species could be taking revenge on us from beyond the grave by making us more vulnerable to potentially killer diseases such as cancer and diabetes.

Neanderthals and modern humans are thought to have co-existed for thousands of years and interbred, meaning Europeans now have roughly 2 per cent Neanderthal DNA.

These 'legacy' genes have been linked to an increased risk from cancer and diabetes by new studies looking at our evolutionary history.

However, it is not all bad news, as other genes we inherited from our species' early life could have improved our immunity to diseases which were common at the time, helping us to survive.

Speaking to MailOnline, professor Chris Stringer, research leader in human origins at the Natural History Museum in London, said: Neanderthals had been evolving outside of Africa for thousands of years and had been exposed to diseases which our species had not come into contact with.

'Studies have shown we could have taken part of our HLA system, which effects our white blood cells, from them.

'We got a quick fix to our own immune system by breeding with Neanderthals which helped us to survive.

'Studies have also already been published which show that humans outside of Africa are more vulnerable to Type 2 diabetes, and that is because we bred with Neanderthals, while those who stayed inside Africa didn't.'

The HLA system helps white blood cells to identify and destroy foreign bodies when they enter the system.

Last year researchers from Oxford and Plymouth universities announced that genes thought to be risk factors in cancer had been discovered in the Neanderthal genome, and last month Nature magazine published a paper from Harvard Medical School suggesting that a gene which can cause diabetes in Latin Americans came from Neanderthals.

By examining the genes found in the toe bone of a female Neanderthal, scientists have been able to build up a more complete version of early human history and how modern-humans evolved.

Analysis of the DNA found thatNeanderthal families were highly interbred, both among themselves, and among other early humans such as Denisovans.

The research potentially suggests that Neanderthals became extinct not because early humans killed them, but because they bred with them and incorporated their DNA into the much larger human population.

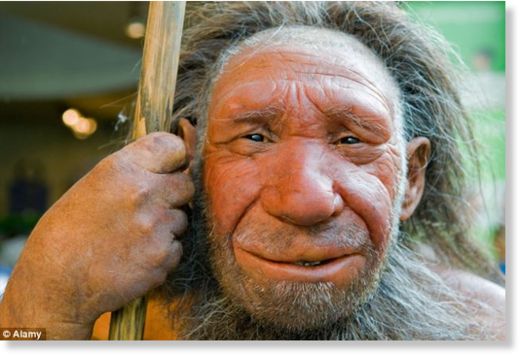

Next month the Natural History Museum will stage an exhibition, Britain: One Million Years of the Human Story, describing Homo erectus, an early human species that first populated Britain about 900,000 years ago, and displaying life-size models of Neanderthals, a later species.

Neanderthals may not, however, be the only contributors to modern human DNA. New studies suggest that during one period, between 100,000-500,000 years ago, there were up to seven species of early human alive at the same time.

People from sub-Saharan Africa, have DNA suspected to come from Homo heidelbergensis - the Heildelberg Man - a primitive ancestor, while some Asian groups carry DNA from the Denisovans.

Reader Comments