The gunmen forced him and other Palestinian refugees in the Sabra and Shatila camps to line up, separated the men and women, and dragged young men from the line to be killed. Abu Jamal's son, 19 at the time, was among those they chose.

"He was in his last year of school," said Abu Jamal, who wears a button with his son's picture on his sweater and asked that his full name not be used. "He never saw his diploma."

Israeli troops did not intervene during the bloodshed, which went down as one of the worst atrocities of Lebanon's 1975-90 civil war. Ariel Sharon, who died on Saturday, was defense minister at the time and many Palestinians in Sabra and Shatila still blame him for the killings.

Over three days, beginning on September 16, 1982, around 2,000 men, women and children were massacred in Sabra and Shatila on the southern outskirts of Beirut. Some 500 more simply vanished without a trace. Israel had invaded Lebanon three months before, and the brutal killings, the work of Israel's Lebanese Phalangist allies, were carried out as Israeli troops surrounded the camps.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, survivors showed little sympathy when they heard of the Israeli commander-cum-politician's passing after eight years in a coma.

Sitting in her home down the street from where a memorial stands at the site of a mass grave, 70-year-old Milany Boutrous Alha Bourje recalled how her husband and son were shot dead that day. Sharon, she said, deserved far worse than he got.

"May God send him deep into the earth," she said, black and white photos of her slain family decorated with red artificial roses leaning against the wall beside her. "I wish he had suffered as we've suffered. Thirty-two years we've been suffering. He was in his state for eight years, but I wished he'd suffered for another 10."

Bourje, who appears in an iconic photograph of the 1982 massacre crying out and waving her arms near a row of bodies, said she was no more optimistic about the future now Sharon was dead. "Nothing changes," she said. "The situation we are living in does not change."

A 1983 Israeli inquiry found Sharon bore "personal responsibility" for not preventing the bloodshed, pushing him to resign as defense minister. But less than two decades later he rose to lead his Likud party and was elected prime minister.

"You want to know how I feel? I want to sing and play music, that is how," said Umm Ali, a 65-year-old woman clad in black whose brother Mohammed was killed in the massacre. "I would have liked so much to stab him to death. He would have suffered more," she said of Sharon, as she walked slowly, linking arms with a young relative.

Shopkeeper Mirvat al-Amine said Sharon should have been put on trial but is confident that he will meet divine justice. "Of course I am happy that he is dead. I would have liked to see him go on trial before the entire world for his crimes but there is divine justice and he cannot escape that. "The tribunal of God is more severe than any court down here," she said.

Outside the shop Magida, aged 40, says she is still haunted by memories of the massacre. She and her family had fled Shatila just before the killings after sensing that something was not right, she said. They sought shelter in an adjacent park and waited.

"A neighbor joined us, her dress was covered in blood. She told us that people were being massacred in the streets," said Magida.

"At first we could not believe it but later we began hearing screams, we heard people begging their assassins to spare them."

Palestinian refugees live in dire conditions in Lebanon, where many are packed into overcrowded, impoverished "camps" which are really more like urban slums of concrete buildings, pot-holed roads and tangled wire.

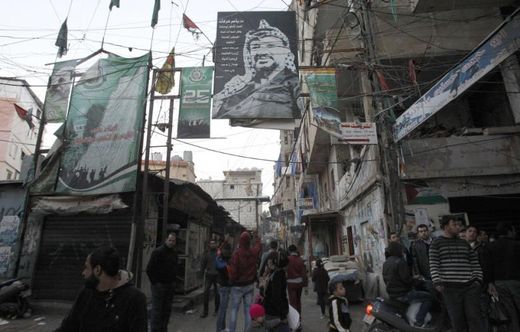

Sabra and Shatila in Beirut are crowded neighborhoods of narrow alleys where pictures of Yasser Arafat, Mahmoud Abbas and young men killed in conflicts with Israel cover many walls.

Standing near a sign at the memorial reading "We will not forget," Youssef Hamzeh, born the year before Israel's 1948 colonization of Palestine, echoed others in the camps when he said Sharon should have been put on trial over the killings.

"As a witness to this person and from what I suffered from this person, I say to hell with Sharon and to Sharon's supporters in the Israeli leadership ... who still commit massacres," he said. "It's not enough that Sharon died."

When Adnan al-Moqdad heard the news about Sharon, he went to the cemetery in Sabra to pray for the soul of his mother and father, killed in the massacre. The Moqdads were Lebanese but like many impoverished families had their home in the sprawling camps.

"How can anyone forget the massacre," he asked "Sharon is responsible. God is Great and he made him suffer to the end of his days and he will make his suffer after his death."

Reader Comments

to our Newsletter